See also

Intravenous immunoglobulin

Febrile child

Sepsis: assessment and management

COVID-19/PIMS-TS (post infectious systemic hyperinflammatory syndrome)

Prolonged fever

Key points

- Criteria for Kawasaki disease (KD) have been updated such that diagnosis can made in the presence of clinical features with 4 or more days of fever

- Timely diagnosis and treatment with IVIg under the guidance of a senior clinician is important to reduce the risk of coronary artery aneurysms (CAAs)

- Consider addition of corticosteroids for children at high-risk of CAAs

- Infants

<12 months who are at a higher risk of incomplete KD and CAAs may present with prolonged fever and fewer clinical features

Background

KD is an acute, idiopathic, medium-sized vessel vasculitis with a predilection for the coronary arteries. KD is the leading paediatric cause of acquired heart disease in high-income countries (including Australia), due to the risk of CAAs

- ~75% of cases occur

<5 years of age

- 2nd most common childhood vasculitis after IgA vasculitis

- Growing incidence worldwide and more common in children of Japanese, Korean or Chinese ethnicity (10-15x higher than Caucasian)

- Diagnosis is often challenging, as there is no specific diagnostic test and features may appear progressively over several days

- Self-limited course, typically resolves by 2-3 weeks, but ~25% of cases develop CAAs if untreated

- KD recurrence is rare, occurring in approximately 1% of cases

Assessment

History

Clinical features can present sequentially over several days. Thus, history should include asking about diagnostic features that may have resolved by the time of presentation (see table below)

Examination

Clinical features of complete KD

- Fever ≥4 days (day 1 = day of fever onset)

AND

- At least 4 principal clinical features at ANY point during illness

(do NOT need to be present simultaneously)

AND

- Illness cannot be better explained by an alternative cause

(see Additional notes for table of differential diagnoses)

|

|

| Principal clinical features |

Findings |

|

Conjunctival injection

|

Bilateral, non-exudative and painless. Often with peri-limbic sparing |

|

Rash

|

Polymorphous, erythematous typically involving the trunk, perineum (may desquamate during fevers) and extremities

NOT typically bullous, vesicular or haemorrhagic

|

|

Erythema of palms and soles

|

Palmar and plantar erythema usually accompanied by painful oedema

AND/OR

Periungual desquamation, typically 2-3 weeks from onset of illness

|

|

Adenopathy (cervical)

|

Cluster of anterior cervical triangle lymph nodes ≥1.5 cm in diameter, usually unilateral and tender |

|

Mucosal changes

|

One or more of:

- Erythematous, fissuring, desquamating or haemorrhagic lips

- Erythematous tongue with prominent papillae ("strawberry" tongue)

- Erythematous oropharynx

NOT typically exudative pharynx or ulcerated mucosa

|

These images have been reproduced with permission from the Kawasaki Disease Foundation, Inc

Other clinical manifestations of KD

| System |

Other clinical manifestations |

| Cardiovascular |

Coronary artery abnormalities (asymptomatic, unless ischaemia which is rare)

Myocarditis, pericarditis, valvular regurgitation, shock

Aneurysms of medium-sized non-coronary arteries (uncommon, usually axillary artery)

Aortic root enlargement (rare)

Peripheral gangrene (extremely rare)

|

| Nervous system |

Extreme irritability

Aseptic meningitis

Sensorineural hearing loss

Cranial nerve palsy (rare)

|

| Gastrointestinal |

Diarrhoea, vomiting, abdominal pain

Hepatitis, jaundice

Gallbladder mucocoele ("gallbladder hydrops")

Pancreatitis

|

| Musculoskeletal |

Arthralgia/arthritis |

| Genitourinary |

Sterile pyuria (nitrite neg, leukocyte esterase ≤1+)

Urine bilirubin ≥1+, urobilinogen ≥1 mg/dL

Dysuria, urethritis/meatitis (rare)

|

| Respiratory |

Peri-bronchial and interstitial infiltrates on CXR

Pulmonary nodules

|

| Other |

Anterior uveitis (common, asymptomatic, requires slit lamp)

Desquamating rash in groin (common acutely in infants)

Erythema and induration at BCG vaccination site (typically within 6 months but seen up to 2-3 years post BCG)

Retropharyngeal phlegmon

|

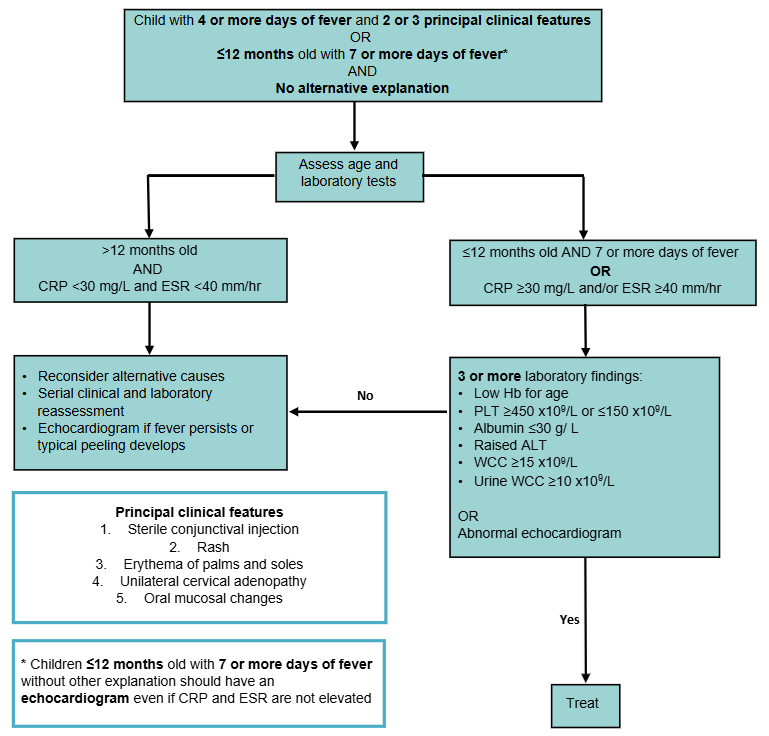

Incomplete KD

Consider in a child with a clinical presentation suggestive of KD but

<4 principal clinical features

- Requires abnormal investigation results to support the diagnosis (see flowchart)

- Infants and adolescents often present with an incomplete picture and are at a higher risk for cardiac complications

- In infants

<12 months with prolonged unexplained fever including those with normal inflammatory markers, echocardiogram is recommended as part of diagnostic assessment

Incomplete KD diagnosis

Adapted from the American Heart Association (2024)

| Abnormal echocardiogram |

Features |

| Coronary artery aneurysm/s |

Z-score ≥2.5 |

| OR 3 or more of the below |

| Decreased left ventricular function |

Ejection fraction:

<55% and/or

Fractional shortening:

<28%

|

| Mitral regurgitation |

Grade: mild or greater |

| Pericardial effusion |

Grade: small or greater |

| Coronary artery dilation |

LAD or RCA Z-score: 2 to 2.5 |

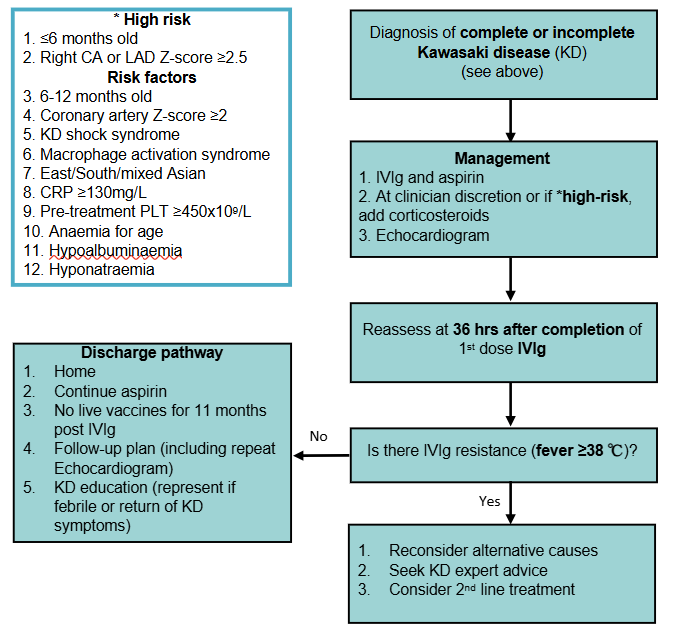

Risk stratification

High-risk for developing coronary artery aneurysm (CAA) (Z-score ≥2.5, irrespective of morphology)

- ≤6 months old

- Right CA or left anterior descending Z-score ≥2.5

Other factors that may increase risk of IVIg resistance and/or CAA

- 6-12 months old

- Coronary artery Z-score ≥2

- Delayed IVIg administration (≥10 days after fever onset)

- IVIg resistance (fever ≥38°C present at 36 hours or more after completion of first dose of IVIg))

- KD shock syndrome (KDSS, see Additional notes) or macrophage activation syndrome (MAS)

- Pre-treatment PLT ≥450x109/L

- CRP ≥130 mg/L

- East/South/mixed Asian ethnicity

- Anaemia for age

- Hypoalbuminaemia

- Hyponatraemia

Management

Investigations

There is no single diagnostic test for KD. Biochemical findings are more sensitive, whilst echocardiographic findings are more specific. Both are used to support diagnosis, assess severity and monitor treatment response

Laboratory

- In all children, consider

- FBE, CRP, ESR, UEC, LFTs (avoid repeating ESR after IVIg as is falsely raised)

- Blood culture

- Urine microscopy and culture (sterile pyuria)

- ECG

- Serum to store (prior to IVIg administration)

- Additional tests

- Concern for systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SoJIA): ferritin

- Concern for MAS: ferritin, fibrinogen, fasting triglycerides

- Concern for PIMS-TS: ferritin, troponin, LDH, CK, NT-proBNP, coagulation studies, D-dimer

Echocardiogram

- May be normal, especially early in the course of the disease and does not exclude a diagnosis of KD. The availability of echocardiography should not delay treatment

- Timing guided by local cardiology service. Suggested schedule:

- Baseline at presentation

- Follow-up at 4-6 weeks

- Earlier follow-up echocardiography under the guidance of a paediatric cardiologist should be considered in all children who are considered high-risk, have baseline CAAs or experience persisting systemic inflammation after

their initial scan

Treatment

First line treatment

Primary therapy (all children with KD)

- Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg): 2 g/kg as a single infusion, usually given at incrementing rates over 8-12 hours

- Early treatment improves coronary artery (CA) outcomes. Timing of delivery should be determined by senior clinician advice and aligned with local protocols

- See Additional notes for advice on timing, prescription and adverse events

- Aspirin: to prevent thrombosis, 5 mg/kg orally daily

- Continue until follow-up cardiology review (~6 weeks post onset)

- Minimal risk of Reye syndrome at this dose. Higher aspirin doses have not been shown to improve CA outcomes

- Avoid NSAIDs whilst on aspirin as ibuprofen may reduce cardioprotective effects

Primary intensification therapy (for children high-risk of CAAs or at clinician discretion)

- Corticosteroids: refer to local protocols or subspecialty advice, example regimen:

- 2mg/kg once daily, IV methylprednisolone or PO prednisolone (max 50mg) tapered over 2-4 weeks depending on response

Second line treatment

If there is IVIg resistance (fever ≥38°C present at 36 hours or more after completion of first dose of IVIg) consider alternative causes and consultation with local KD experts (eg infectious diseases, rheumatology, immunology)

Further treatment may include a second dose of IVIg. Consider addition of infliximab or corticosteroids if not already given. Refer to local protocols or subspecialty advice

Additional treatment

Antithrombotic therapy for CAAs should be managed in consultation with local cardiology services

Additional therapy (for refractory KD not responding to above treatment)

- Consult local KD experts

- Therapeutic options that may be considered include: anakinra, etanercept, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, plasmapheresis

Resolving KD

- Suspected previous KD illness in convalescent phase ie no evidence of active inflammation (no fever, normal inflammatory markers)

- Commence aspirin (see dosing above) and refer for echocardiogram

Consider consultation with local paediatric team when

Consider transfer when

- Child has cardiac involvement, or timely echocardiography is unavailable locally

- Children requiring care above the level of comfort of the local hospital

For emergency advice and paediatric or neonatal ICU transfers, see Retrieval Services

Consider discharge when

- Afebrile and well ≥36 hours after treatment and daily aspirin provided

- Follow-up plan is in place, including a repeat echocardiogram

- CRP repeated to ensure normalisation, may be considered in some high-risk children

- KD education provided (represent if febrile or return of KD symptoms)

Parent information sheets

RCH Kid's Health Info: Kawasaki disease

Sydney Children's Hospital network fact sheets: Kawasaki disease

Kawasaki Disease Foundation Australia

Immunisation guidance

Additional notes

Definitions

- Atypical KD: preferably avoided to prevent confusion, description for unusual presentations, eg CNS manifestations

- KD Shock Syndrome (KDSS): severe form presenting with hypotension, poor perfusion or myocardial dysfunction. Consider slower IVIg infusion time

Considerations in IVIg use

- Authorised by the National Blood Authority (through BloodSTAR) and issued by Australia Red Cross Lifeblood

- Timing

- Local infusion guidelines may suggest delaying until daytime staffing if not clinically urgent, eg haemodynamically stable, ≤7 days of fever

- Administer without delay when clinically safe. IVIg should still be given >10 days of fever if there is evidence of active inflammation, ie fever, elevated inflammatory markers, abnormal CA

- Adverse effects

- Haemolytic anaemia is a rare (~1%) dose-dependent complication, more frequent in non-O blood types

- Headache

- Fever during infusion may reflect KD activity rather than a transfusion reaction. Consider paracetamol 30 mins prior and regularly during infusion

- Vaccination post IVIg

- Live vaccine immunisation (eg MMR, MMRV, Varicella, Rotavirus) should be delayed for 11 months post IVIg administration (see National Immunisation Handbook).

If there is high risk of measles exposure, vaccinate and repeat immunisation after 11 months

- Further information, see Intravenous Immunoglobulin

Differential diagnoses causing fever

| Group A streptococcal (GAS) infections |

- Pharyngitis, scarlet fever, acute rheumatic fever, retropharyngeal or parapharyngeal abscess

- Consider KD in children who show no clinical improvement after 24-48 hours of appropriate antibiotics

|

| Viral infections including adenovirus, enterovirus, EBV, CMV, HHV-6, parvovirus B-19, SARS-CoV, influenza |

- Positive respiratory virus PCR does not exclude a diagnosis of KD (~1/3 of KD cases will be positive)

- Unlike adenovirus, KD conjunctivitis is typically non-exudative, bilateral and characteristically spares the limbus

- Adenovirus typically causes exudative conjunctivitis and pharyngitis

|

| Measles |

- Cough, coryza, exudative conjunctivitis without limbal sparing and cephalocaudal rash

- Unimmunised children higher risk

|

| Bacterial cervical lymphadenitis |

- KD lymphadenopathy is usually not responsive to antibiotics and unilateral, often appearing as a cluster of enlarged nodes ("grape-like")

|

| Viral meningitis |

- Consider KD in an infant with prolonged fever and unexplained irritability/aseptic meningitis

|

| Urinary tract infection |

- KD typically presents with sterile pyuria and urine dipstick findings: nitrite negative, leukocyte esterase ≤1+, urine bilirubin ≥1+, urobilinogen ≥1 mg/dL

|

| Sepsis or staphylococcal or streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (TSS) |

- TSS is usually characterised by hypotension, multiorgan dysfunction and rapid progression to shock

- ~5% KD cases present with KDSS which is associated with a higher risk for CAAs

|

| Malignancy |

- Subacute or chronic presentation with anaemia, recurrent infections, unusual bruising/bleeding or B symptoms (lymphadenopathy, night sweats, weight loss)

|

| PIMS-TS (post-infectious systemic hyperinflammatory syndrome)/MIS-C (multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children) |

- Prominent gastrointestinal symptoms (abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhoea), headache and history of proven/suspected COVID-19 infection 2-6 weeks prior

|

| Still's disease/SoJIA |

- >7 days of quotidian (once or twice daily) high-spiking fevers with a low baseline, otherwise well, transient salmon-pink rash accentuated with fever with or without joint pain/swelling

|

| Drug hypersensitivity reactions including toxic epidermal necrolysis |

- Ulcerated mucosa (mouth, eyes, genital) with triggering medication or infection

|

Last updated January 2026

Reference list

- Jone, P.-N. et al. (2024) ‘Update on diagnosis and management of Kawasaki Disease: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association’, Circulation, 150(23). doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000001295.

- American Heart Association. (2017). Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki Disease. Circulation, 135. DOI: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000484

- Bernard, R., Whittemore, B., & Scuccimarri, R. (2012). Hemolytic anemia following intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in patients treated for Kawasaki disease: a report of 4 cases. Pediatric Rheumatology Online Journal. 10. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-10-10

- Broderick, C. et al. (2023). Intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment of Kawasaki disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD014884.pub2.

- Shulman ST, Rowley AH. Kawasaki disease: insights into pathogenesis and approaches to treatment. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2015 Aug;11(8):475-82.

- Burns, J., Roberts, S., Tremoulet, A., He, F., Printz, B., Ashouri, N., et al. (2021). Infliximab versus second intravenous immunoglobulin for treatment of resistant Kawasaki disease in the USA (KIDCARE): a randomised, multicentre comparative effectiveness trial. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. 5(12):852–61.

- Butters, C., Curtis, N., Burgner, D. P. (2020). Kawasaki disease fact check: Myths, misconceptions and mysteries. J Paediatr Child Health, 56(9), 1343-1345.

- Cardenas-Brown, C. et al. (2023). Live vaccines following intravenous immunoglobulin for Kawasaki disease: Are we vaccinating appropriately? J Pediatr Child Health. 59(11):1217-1222

- Catella-Lawson, F. et al (2001). Cyclooxygenase inhibitors and the antiplatelet effects of aspirin. N Engl J Med. 20;345(25):1809-17

- Cohen, E. & Sundel, R. (2016). Kawasaki Disease at 50 years. JAMA Paediatrics, 170(11). Pp. 1093 – 1099.

- Dallaire, F. et al. (2017). Aspirin dose and prevention of coronary abnormalities in Kawasaki Disease. Paediatrics, 139(6). DOI: e20170098

- Dhanrajani, A., Chan, M., Pau, S., Ellsworth, J., Petty, R., & Guzman, J. (2017). Aspirin dose in Kawasaki Disease: the ongoing battle. Arthritis Care & Research, 70(10), pp. 1536-1540. DOI: 10.1002/acr.23504

- Guo Yang Ho, L. Curtis, N. (2017). What dose of aspirin should be used in the initial treatment of Kawasaki Disease? Archives of Disease in Childhood, 0, pp 1 – 3. Doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-313538

- Hamanaka, S. et al. (2025). Evaluation of Risk Factors of Coronary Artery Abnormalities in Incomplete Kawasaki Disease: An Analysis of Post RAISE. J Paediatr Child Health doi: 10.1111/jpc.70120

- Hedrich, C. M., Schnabel, A., & Hospach, T. (2018). Kawasaki Disease. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 6(198). doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00198

- Ho, L. G. Y., Curtis, N. (2017). What dose of aspirin should be used in the initial treatment of Kawasaki disease? Arch Dis Child, 102(12), 1180-1182

- Huuang, X., Huuang, P., Zhang, L., Xie, X., Gong, F., Yuuan, J., & Jin, L. (2018). Is aspirin necessary in the acute phase of Kawasaki disease? Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 54, pp. 661-664. doi:10.1111/jpc.13816

- Burns JC. Frequently asked questions regarding treatment of Kawasaki disease, Global Cardiology Science and Practice 2017:30, http://dx.doi.org/10.21542/gcsp.2017.30

- Jiang, L., Tang, K., Levin, M., Irfan, O., Morris, S. K. et al. (2020). COVID-19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adolescents. Lancet Infectious Diseases. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30651-4

- Kanegaye, J. et al. (2025). Urinary Abnormalities Differentiating Kawasaki Disease from Clinically Similar Febrile Illnesses. Paediatrics Open Science

- Kobayashi, T. et al. (2013). Efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulin combined with prednisolone following resistance to initial intravenous immunoglobulin treatment of acute Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr 163(2):521-6

- Marchesi, A. et al. (2018). Kawasaki disease: guidelines of the Italian Society of Pediatrics, part I – definition, epidemiology, etiopathogeneis, clinical expression and management of the acute phase. Italian Journal of Pediatrics 44(102). doi.org/10.1186/s13052-018-0536-3

- Miyata, K. et al (2023). Infliximab for intensification of primary therapy for patients with Kawasaki disease and coronary artery aneurysms at diagnosis. Arch Dis Child 108(10):833-838

- Perth Children’s Hospital clinical practice guidelines. (2018). Kawasaki Disease. https://pch.health.wa.gov.au/For-health-professionals/Emergency-Department-Guidelines/Kawasaki-disease

- Tsoi, S.K., Burgner, D., Ulloa-Gutierrez, R. and Phuong, L.K. (2024). An Update on Treatment Options for Resistant Kawasaki Disease. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, 44(1), pp.e11–e15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/inf.0000000000004561.

- Renton, W., Carmody, J., Mactaggart, E., Akikusa, J. (2025). The Role of Early Echocardiography in Low-Risk Patients with Kawasaki Disease. J Paediatr Child Health. 61(8):1301-1305

- Rigante, D., Andreozzi, L., Fastiggi, M., Bracci, B., Natale, M. F., & Esposito S. (2016). Critical overview of the risk scoring systems to predict non-responsiveness to intravenous immunoglobulin in Kawasaki Syndrome. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 17 (278). doi:10.3390/ijms17030278

- Sevenoaks, L., & Tulloh, R. (2020). Should we use steroids as primary therapy for Kawasaki disease? Archives of Disease in Childhood Published Online First: 03 August 2020. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319231

- Singh, S., Jindal, A. K., & Pilania, R. K. (2018). Diagnosis of Kawasaki disease. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases, 21, pp. 36-44.

- Starship Clinical Guidelines. (2024). Kawasaki Disease. https://www.starship.org.nz/guidelines/kawasaki-disease/

- Wardle, A. J., Connolly, G. M., Seager, M. J., & Tulloh, R. M. R. (2017). Corticosteroids for the treatment of Kawasaki disease in children (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011188.pub2.

- Younger, D. (2019). Epidemiology of the Vasculitides. Neurologic Clinics, 37 (2), pp. 201

- Beth, M., Gauvreau, K., Levin, M., Lo, M.S., Baker, A.L., Sarah, Fatma Dedeoglu, Sundel, R.P., Friedman, K.G., Burns, J.C. and Newburger, J.W. (2019). Risk Model Development and Validation for Prediction of Coronary Artery Aneurysms in Kawasaki Disease in a North American Population. 8(11). doi:https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.118.011319.