See also

Gastrooesophageal reflux in infants

Afebrile seizures

Child Abuse

Key points

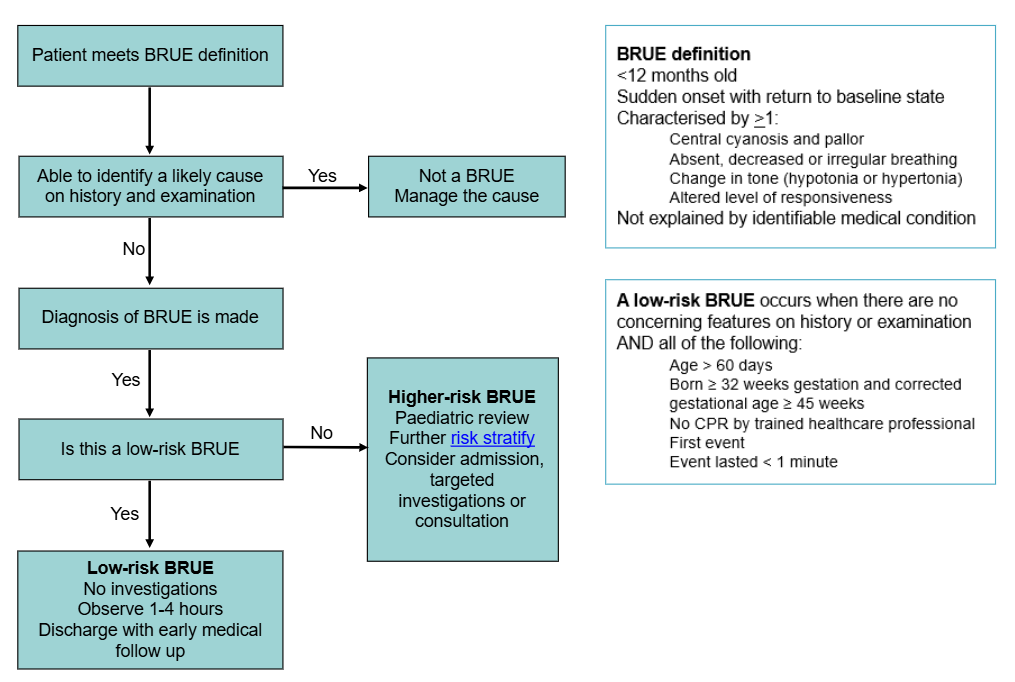

- Most infants presenting with a brief resolved unexplained event (BRUE) do not have a serious underlying diagnosis

- For higher-risk BRUE consider investigation and consultation as indicated. Hospital admission for observation may provide parental reassurance

- A low-risk BRUE may be safely managed in an outpatient setting without investigations

Background

A BRUE is defined as an event occurring in an infant less than 12 months old where the following is observed

- Sudden, brief and now resolved

- Characterised by one or more of the following

- cyanosis or pallor

- absent, decreased or irregular breathing

- marked change in tone (hypertonia or hypotonia)

- altered level of responsiveness

- Where alternative differential diagnoses have been excluded after history and physical examination

The most common cause of these events is thought to be exaggerated airway reflexes secondary to poor suck/swallow coordination or vagal stimulation; in the setting of feeding, gastro-oesophageal reflux or increased upper respiratory tract infections.

Assessment

History

History should be taken from an adult who observed the event

Consider inflicted injury when multiple or changing versions of the history are provided or circumstances are inconsistent with the child's developmental stage

Key features may include the following:

Description of event

- Choking, gagging

- Breathing: difficulty breathing, pauses, apnoea

- Colour and colour distribution: normal, cyanosis, pallor, plethora

- Distress

- Conscious state: responsive to voice, touch, or visual stimulus

- Tone: stiff, floppy, or normal

- Movement (including eyes): purposeful, repetitive

Circumstances and environment prior to event

- Awake or asleep

- Relationship of the event to feeding and history of vomiting

- Position (prone/supine/side)

- Environment: sleeping arrangement, co-sleeping, temperature, bedding

- Objects nearby that could be swallowed, cause choking or suffocation

- Illness in preceding days

End of event

- Duration of event

- Circumstances of cessation: self-resolved, repositioned, stimulation, mouth to mouth and/or chest compressions

- Recovery phase: rapid or gradual

Other history

- Past medical history

- Previous similar event or multiple events/clusters

- Preceding/intercurrent illness

- Baseline stridor/stertor/vomiting or symptoms of GORD

- Sick contacts

- Family history of sudden death or significant childhood illness

- Patient medications or other drugs within the home

- Social history: parental supports, psychosocial assessment

Examination

All children should be completely exposed for a complete examination

Any bruising, subconjunctival haemorrhage, full fontanelle, head circumference crossing centiles, epistaxis, oral injury or irritability/drowsiness should raise suspicion for inflicted injury

Other relevant examination

- Growth parameters

- Stridor/stertor/WOB

- Detailed cardiac, respiratory, neurological, and other relevant system examination

Differential diagnoses

Less serious (more common)

- Laryngospasm, choking, gagging

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux

- Normal infant movement, periodic breathing

- Lower respiratory tract infection

More serious (less common)

- Seizure/infantile spasms

- Airway abnormalities or obstruction

- Apnoea (central/obstructive)

- Head injury/other inflicted injuries

- Infections: pertussis, bacterial infection

- Cardiac: congenital heart disease, arrhythmias

- Other: electrolyte abnormality, inborn errors of metabolism, toxin/ingestion, intussusception

BRUE risk stratification

If the infant has recovered and examination is benign, the event can be risk stratified

A low-risk BRUE is very unlikely to represent presentation of a serious underlying disorder and is unlikely to recur

A low-risk BRUE has no concerning features on history or examination AND all the following criteria

- age >60 days

- born ≥32 weeks gestation and corrected gestational age ≥45 weeks

- no CPR by trained healthcare professional

- first event

- event lasted <1 minute

Patients not meeting these criteria have a higher-risk BRUE

- 4-8% of infants with higher-risk BRUE will have a serious underlying diagnosis, most commonly seizure or apnoea

Management

Investigations

A low-risk BRUE does not require any investigations

Diagnostic testing in higher-risk BRUE is low-yield and rarely contributes to an explanation. Recent studies show investigations contribute to diagnosis in only 1-7% of tests performed

For higher-risk BRUE, consider the following investigations/consultations as indicated

| Investigation/action |

Reason to consider |

| ECG (measure QT interval) |

Dysmorphology or family history of arrhythmia or sudden death |

| Nasopharyngeal sample |

History of pertussis exposure, respiratory symptoms, apnoea |

| EEG/ Neurology consultation |

Abnormal movements, eye deviation or altered neurology, event recurrence |

| ENT consultation |

Stridor, epistaxis, obstructive symptoms or apnoea |

Treatment

- Acknowledge the distress that this event may have caused carer. Provide education and reassure them that these infants are not at an increased risk of death

- If the infant requires ongoing acute treatment, the event is not a BRUE

- Infants who have had a low-risk BRUE may be discharged safely if their parents feel reassured and capable of caring for their infant at home

- Admission for observation and cardiorespiratory monitoring can provide reassurance but uncommonly leads to a diagnosis

- For low-risk BRUE, shared decision making with families regarding whether an admission for observation is of benefit

- If discharged, it is recommended that families of these children receive clear advice about when to return and that there is a safety net in place about when to re-present

- Although the infant is not at increased risk of premature death, families should be offered resources for infant CPR training

Consider consultation with local paediatric team when

The event does not meet low-risk BRUE criteria

Any concerns for inflicted injury

Consider transfer when

A serious underlying disorder is suspected

For emergency advice and paediatric or neonatal ICU transfers, see Retrieval services.

Consider discharge when

- After a period of observation if there is a low clinical suspicion of a serious underlying disorder

- Carer is reassured

Parent information

BRUE Parent Handout (American Association of Paediatrics)

CPR training (RCH Kids Health Info)

Last updated January 2026

Reference list

- Bochner R et al. Explanatory Diagnoses Following Hospitalization for a Brief Resolved Unexplained Event. Pediatrics. 2021;148(5):e2021052673.

- BRUE 2.0 Calculator. MD Calc. Retrieved from https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/10400/brief-resolved-unexplained-events-2.0-brue-2.0-criteria-infants#next-steps (Viewed Apr 2025)

- Mittal M et al. Diagnostic testing for evaluation of brief resolved unexplained events. Acad Emerg Med. 2023 Jun;30(6):662-670.

- Nama N et al. Nama N. et al. Identifying serious underlying diagnoses among patients with brief resolved unexplained events (BRUEs): a Canadian cohort study. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2024;8(1).

- Nama N et al. Risk Prediction After a Brief Resolved Unexplained Event. Hosp Pediatr. 2022;12(9):772-785.

- Starship Child Health, BRUE brief resolved unexplained events. Retrieved from https://starship.org.nz/guidelines/brue-brief-resolved-unexplained-events/ Viewed May Apr 2025)

- Tieder J et al. Brief Resolved Unexplained Events (Formerly Apparent Life-Threatening Events) and Evaluation of Lower-Risk Infants. Pediatrics. 2016;137(5):e20160590.