See also

Fever and suspected or confirmed neutropenia

Fever in the recently returned traveller

Kawasaki disease

Petechiae and Purpura

Sepsis – assessment and management

Local antimicrobial guidelines

Key points

- Febrile neonates ≤28 days of corrected age require investigations (FBE, CRP, blood, urine and CSF cultures ± CXR) and empiric IV antibiotic therapy

- In Febrile infants >28 days of corrected age and

<3 months, have a low threshold for investigation and treatment based on clinical appearance and presence (or absence) of a clinically obvious focus

- In infants

<3 months of age, hypothermia or temperature instability can be signs of serious bacterial infection (or other serious illness)

- The severity of illness cannot be predicted by the degree of fever, its rapidity of onset, its response to antipyretics or the presence of febrile seizures; the appearance of the child is the most useful indicator

Background

- Definition of fever: body temperature >38.0º Celsius

- Where possible, use the same body site and the same type of thermometer when measuring temperatures (see Additional notes below)

- The most common causes of fever in children are viral infections, however serious bacterial infections (SBIs) need to be considered

- The most common SBIs found in children without a focus are urinary tract infections

- Other SBIs to consider include:

pneumonia,

meningitis,

bone and joint infections,

skin and soft tissue infections, mastoiditis, bacteraemia,

sepsis

- Since the introduction of the pneumococcal vaccine, the rate of occult bacteraemia has fallen to

<1% in healthy, immunised children

- Children with fever for ≥5 days should be assessed for

Kawasaki disease or

PIMS-TS if there is a history of COVID-19 infection

- Other uncommon causes of prolonged fever in children include inflammatory, immune-mediated and neoplastic conditions; specialist input may be required

Assessment

History

- Localising symptoms eg cough, headache, photophobia, diarrhoea, vomiting, abdominal pain, musculoskeletal pain, rash

- Travel

- Sick contacts

- Immunisation: children

<6 months age or with incomplete immunisation

- Medication: prior treatment with antibiotics may mask signs of a bacterial infection

- High risk: prematurity, immunosuppression/oncological conditions (see

Fever and suspected or confirmed neutropenia), central line in situ, chronic lung disease, congenital heart disease, previous invasive bacterial infections, children of Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander, Pacific Islander or Maori origin, multiple health service presentations

Notes

- Teething does not cause fever

- Post vaccination fever is common, with a typical onset within 24 hours of immunisation and duration up to 2-3 days; however, in an unwell child, fever should not be attributed to vaccination alone

Examination

Certain aspects of the child's behaviour and appearance provide the best indication of whether they are at high risk of SBI

Features suggestive of an unwell child

Colour |

Pallor (including parent/carer report)

Mottled

Blue/cyanosed |

|

Activity |

Lethargy or decreased activity

Not responding normally to social cues

Does not wake or only with prolonged stimulation, or if roused, does not stay awake

Weak, high-pitched or continuous cry |

|

Respiratory |

Grunting

Tachypnoea

Increased work of breathing

Hypoxia |

|

Circulation and Hydration |

Poor feeding

Dry mucous membranes

Persistent tachycardia

Central capillary refill time ≥3 seconds

Reduced skin turgor

Reduced urine output |

|

Neurological |

Bulging fontanelle

Excessive irritability

Neck stiffness

Focal neurological signs

Focal, complex or prolonged seizures |

|

Other |

Non-blanching rash

Fever for ≥5 days

Swelling of a limb or joint

Non-weight bearing/not using an extremity |

Adapted from: Feverish illness in children

NICE guideline 2019

The child should be examined for a clinical focus of infection

- Remove clothing as required to complete a full examination, looking for subtle signs

Management

- Any febrile child who appears seriously unwell should be managed as suspected sepsis (see Sepsis), irrespective of the degree of fever

- Do not accept apparent otitis media or upper respiratory symptoms as the source of infection in young infants or unwell children. These children still require assessment for possible SBI

- If the child is stable, it is preferable to complete investigations looking for an infective focus before commencing antibiotics

- In children from high risk groups, have a lower threshold for investigations

- UTI is the most common SBI, if there is no clinically obvious focus for fever, urine collection and testing should be performed

- When blood cultures are indicated, ensure adequate volume collected (see Additional notes below)

- Antimicrobial recommendations may vary according to local antimicrobial susceptibility patterns; please refer to

local guidelines

Infants ≤ 28 days corrected age

- Assess promptly for signs of sepsis and discuss with a senior doctor. See

Recognition of the seriously unwell neonate and young infant

- FBE, CRP, blood culture, urine (by SPA; see section on Urine collection below for other methods), LP ± CXR

- Prompt treatment with empiric

antibiotics

- If the infant appears unwell, or there is likely to be a delay in completing all of the required investigations, proceed with administration of antibiotics

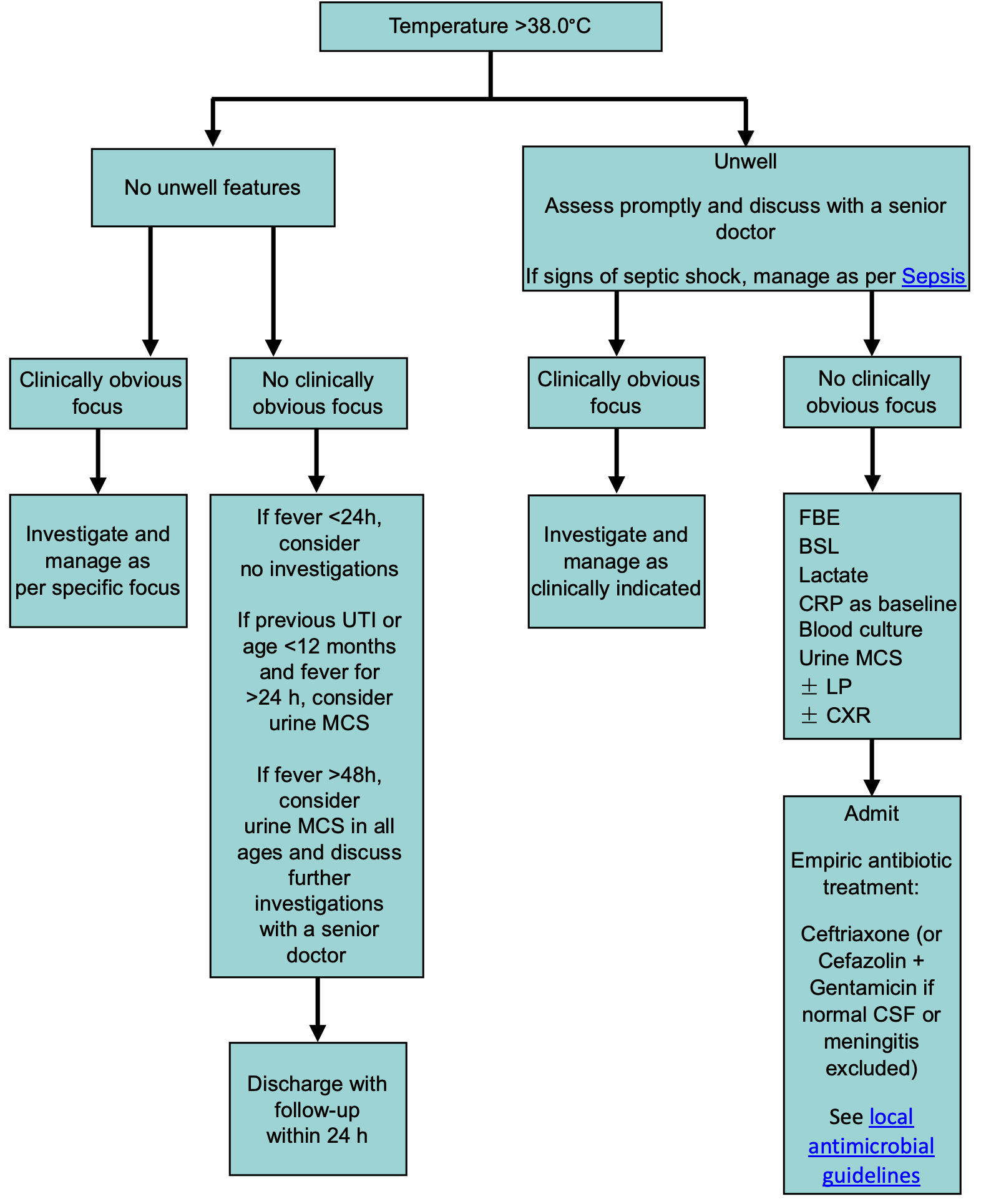

Infants 29 days to 3 months corrected age

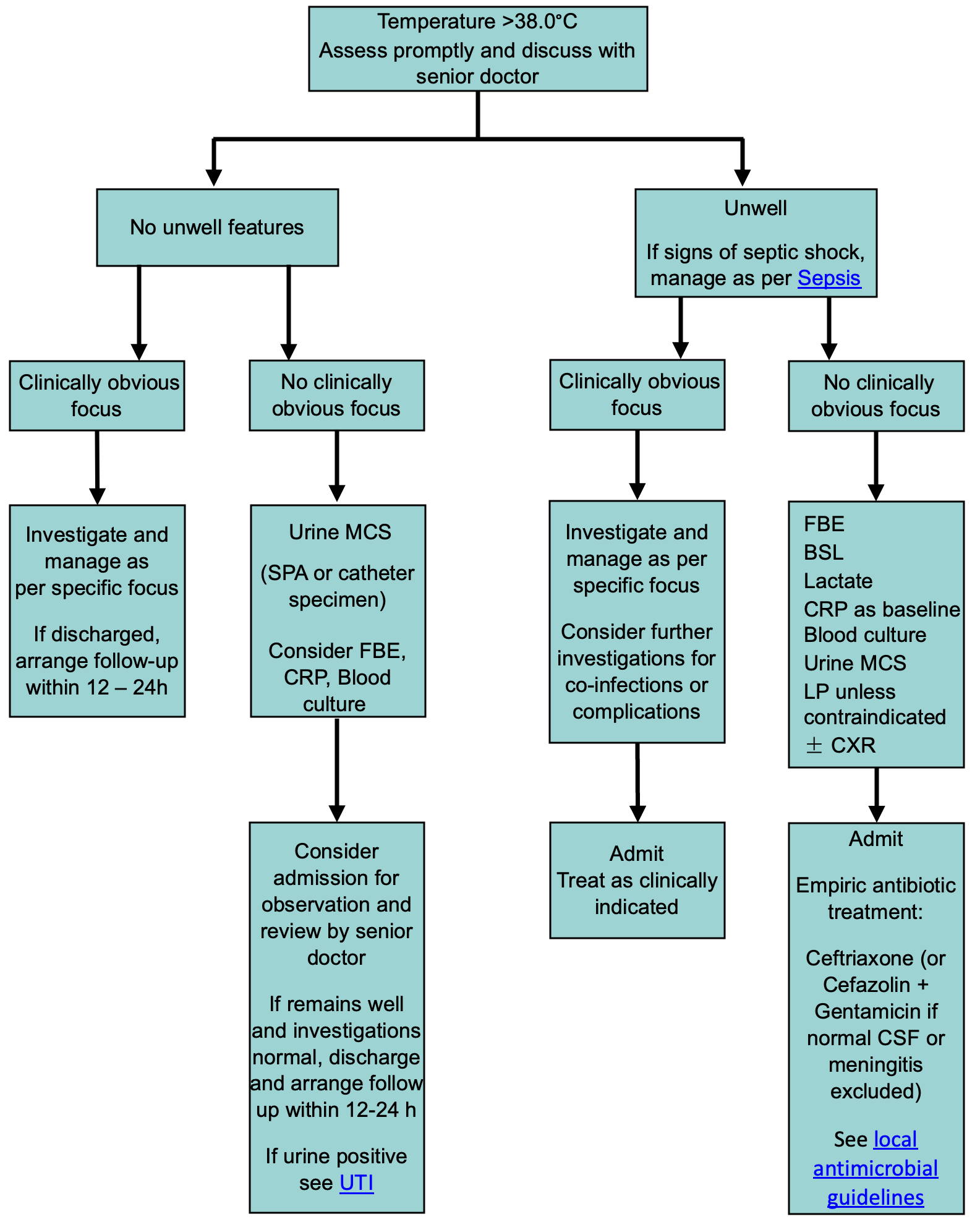

Children >3 months corrected age

Consider consultation with local paediatric team when

- Unwell child

- Septic shock

- Infants

<28 days corrected age with fever (should be admitted for empiric antibiotics)

- Barriers to follow-up within 24 hours due to social or external factors (consider admission)

- High-risk child

- Advice needed regarding empiric treatment

- Prolonged fever of unclear cause

Consider transfer to tertiary centre when

Child requiring care above the level of comfort of the local hospital

For emergency advice and paediatric or neonatal ICU transfers, call the Paediatric Infant Perinatal Emergency Retrieval (PIPER) Service: 1300 137 650

Consider discharge when

- Infants 29 days to 3 months of corrected age: well, investigations normal, discussed with senior doctor, follow-up within 12-24 hours has been arranged

- Children >3 months corrected age: well, follow up has been arranged

- Always advise parents to return for review if the child is deteriorating

Parent Information

Fever in children

Additional resources

Fever in under 5s: assessment and initial management. NICE guideline 2019

Additional notes

Temperature measurements

- Axillary temperature: recommended for infants

<3 months of age

- For a more accurate reading, the thermometer should be placed over the axillary artery for 3 minutes.

- Tympanic temperature: recommended for children >3 months of age. For an accurate measurement, the pinna must be retracted to straighten the external auditory meatus and the instrument should be directed at the tympanic membrane.

- Skin temperature: forehead or infrared thermometers are unreliable

- Rectal temperature: in neonates, screen first with axillary temperature, then consider performing a rectal temperature if a fever is still suspected

Lumbar puncture

- When indicated, LP should be performed without delay and, ideally, before the administration of antibiotics

- Contraindications to LP include impaired conscious state, focal neurological signs, impaired coagulation or haemodynamic instability

- In this circumstance, treatment for meningitis/encephalitis should be commenced and an LP performed when the child is stable and there are no contraindications

- See

Lumbar puncture

Urine collection

- Bag urine specimens should never be sent for culture due to high false positive rates - contamination rate 50%

- Suprapubic aspirate (see

SPA): gold standard - contamination rate 1%

- In/out catheter: useful if there is little urine in the bladder, such as after failed clean catch or SPA (discard first few drops of urine if possible to reduce contamination) - contamination rate 10%

- Midstream urine (MSU): preferred method for toilet-trained children who can void on request - contamination rate 25%

- Clean catch: appropriate for pre-continent children who cannot void on request, but are not seriously unwell (yield may be improved by gently rubbing child’s suprapubic area with gauze soaked in cold fluid, see

urine tests) - contamination rate 25%

The perineal/genital area should be cleaned with saline-soaked gauze for 10 seconds before collecting midstream or clean catch urine

See

Urinary tract infection

Blood culture

- Blood cultures should be taken using an aseptic technique and sterile gloves

- Accuracy of blood culture results rely on correct blood volume to improve detection of bacteraemia or fungaemia

- Inoculate aerobic bottle preferentially, ie if inadequate volume for both bottles

Volume and type of blood culture:

Weight |

Paediatric aerobic bottle (for small volumes) |

Adult aerobic bottle |

Adult anaerobic bottle |

|

Min vol: 0.5 mL

Max vol: 4 mL |

Min vol: 5 mL

Max vol: 10 mL |

|

<1.5 kg |

1 mL |

|

N/A (unless specific clinical indication) |

|

1.5-5 kg |

1.5 mL |

|

|

5-10 kg |

3 mL |

|

5 mL |

|

11-15 kg |

4 mL |

|

5 mL |

|

16-20 kg |

Use green bottle whenever >4 mL collected |

6 mL |

If anaerobic BC not indicated, put 10 mL in aerobic bottle |

6 mL |

|

21-25 kg |

8 mL |

8 mL |

|

>25 kg |

10 mL |

10 mL |

Last update September 2022