See also

Febrile seizure

Emergency drug dose calculator

Emergency medication and resuscitation resources

Resuscitation guidelines

Key points

- Aim to identify reversible causes and manage accordingly

- Most seizures will resolve within 5 minutes and do not require medications

- Commence pharmacological management if total seizure duration is ≥5 minutes or unknown

- Include pre-hospital doses of benzodiazepines in active management

- Ensure parental education regarding safety and future seizures

Background

- Seizures are common, 1 in 20 (5%) children will have a seizure of some form during childhood

- Most seizures are brief and self-limiting, generally ceasing within 5 minutes

- Seizures should be treated immediately in the following situations

- child seizing with duration unknown, or seizure for >5 minutes

- cardio-respiratory compromise

- known pathology

- meningitis

- hypoxic injury

- trauma

Assessment

Assessment and management should occur concurrently if the child is seizing

Key considerations in acute assessment

- Duration of seizure including pre-hospital period

- Any benzodiazepine doses given to treat the seizure immediately prior to arrival at hospital

- Past history: previous seizures and anti-seizure medication (management plan if in place), neurological comorbidity (eg VP shunt, structural brain abnormality), renal failure (hypertensive encephalopathy), endocrinopathy (electrolyte disturbance)

- Focal features

- Evidence of underlying cause that may require additional specific emergency management. Underlying causes include

- hypoglycaemia

- electrolyte disturbances (hyponatraemia, hypocalcaemia, hypomagnesaemia)

- meningitis

- drug/toxin overdose or envenomation

- head trauma

- stroke and intracranial haemorrhage

- Age: treatable cause is more likely in children

<6 months

- Consider pyridoxine dependent seizures

History

Detailed chronological history of events and behaviours before, during and after the seizure

History should be taken from the child if possible and obtain bystander account, including video recordings

Ask about

- aura, focal features

- level of awareness

- recent trauma, consider non-accidental injury

- focality of limb or eye movement

- post-ictal phase/hemiparesis

- relation to sleep-wake cycle

Relevant past history

- Family history of seizures or cardiac disorders/sudden death

- History suggestive of absence seizures or myoclonic jerks, nocturnal events

- Developmental history

Examination

- Full neurological examination looking for any abnormal neurological findings, signs of meningitis or raised intracranial pressure

- Cardiovascular examination including BP

- Look for any signs that suggest an underlying cause eg neurocutaneous stigmata, microcephaly

- Assess for features of a toxidrome (tachycardia, tachypnoea, hypertension, raised temperature, diaphoresis, diarrhoea, tremors, hyperreflexia)

Red Flags

- Head injury with delayed seizure

- Developmental delay or regression

- Headache prior to the seizure

- Hypertension

- Bleeding disorder, anticoagulation therapy

- Features suggestive of toxidrome

- Focal signs

- History or examination findings concerning for non-accidental injury

- Arrhythmia (seizure may be cause or result of arrhythmia; consider ECG)

Differential diagnosis of seizure including

- Arrhythmia

- Breath holding spell (episode occurs when the child is crying)

- Vasovagal syncope with anoxic seizure (postural change, preceded by dizziness and nausea)

- Paroxysmal non-epileptic events (PNEEs)

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux (Sandifer syndrome)

- Gratification disorder (infantile masturbation)

- Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES)

- Benign infantile movements (shudder, sleep myoclonus)

Management

Most seizures well self-terminate within 5 minutes without intervention, and unless there is airway compromise it is appropriate to observe only during this period without intervention, in line with seizure first aid advice

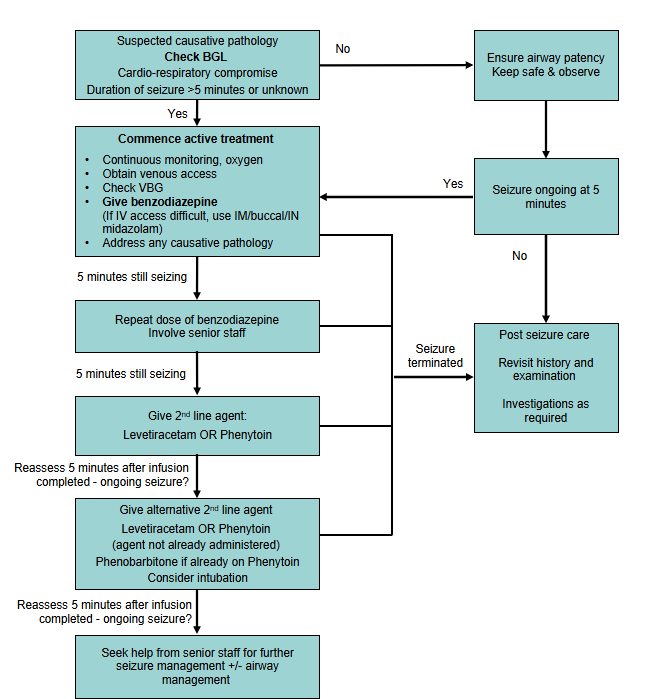

Active seizure flowchart

- Take into account benzodiazepine doses given pre-hospital (eg by parents or paramedics)

- Ensure a maximum of 2 appropriate doses of benzodiazepine are administered (including pre-hospital doses)

- If available, refer to patient specific seizure management plan in children with a known seizure disorder

- Do not give a medication to which the child is allergic or has previously been unsuccessful in terminating the seizure

- In children already on phenytoin use phenobarbitone as alternative 2nd line agent

Medications used in acute seizures

| Medication |

Dose |

Comments |

| 1st line |

| Midazolam |

0.15 mg/kg IV/IM/IO (max 10 mg)

0.3 mg/kg buccal/IN (max 10 mg) |

Injection solution may be given orally, buccally or intranasally, an oromucosal product is also available and is only for buccal use

Intranasal midazolam may cause nasal irritation and a burning sensation |

| Diazepam |

0.3 mg/kg IV/IO (max 10 mg) |

IV dose preferable

Do not give IM |

| 2nd line |

| Phenytoin |

Loading dose:

20 mg/kg IV/IO (max 2 g) |

Use undiluted or dilute to 5 mg/mL or greater and infuse at 1 mg/kg/minute with a maximum rate of 50 mg/minute

Cardiac monitoring required

Contraindicated in Dravet syndrome |

| Levetiracetam |

40-60 mg/kg IV/IO (max 4.5 g) |

Dilute to 50 mg/mL and infuse over 5 minutes |

| Phenobarbitone |

20 mg/kg IV/IO (max 1 g) |

Dilute to 20 mg/mL or weaker and infuse over 30 minutes or longer (max rate 1 mg/kg/minute)

Cardiac monitoring required

Commonly used in neonatal seizures |

| Valproate |

20-40 mg/kg (max 3 g) |

Infuse over 3-10 minutes as a single dose

Not recommended in children <3 years (high risk of hepatotoxicity)

Stop immediately if skin reaction or signs of hypersensitivity (with or without rash), hepatotoxicity

or pancreatitis occur |

| 3rd line |

| Pyridoxine |

100 mg IV |

Consider in children up to 6 months with seizures refractory to standard anticonvulsants |

For refractory seizures requiring rapid sequence induction and ventilation. Use only with involvement of senior staff confident with airway management

Medications may include infusions of midazolam, ketamine, propofol, thiopentone |

Post seizure care

Position child in recovery position, maintain airway

Monitor for further seizure activity

Consider investigations as appropriate

Investigations

Bloods

Blood glucose

Consider electrolytes, calcium and venous gas in the following circumstances:

- any seizure needing a second line agent

- children

<12 months

- medical comorbidity such as metabolic disorder, diabetes, dehydration, toxidrome

- child has not returned to baseline once the post-ictal phase and the effect of any medication has passed

ECG

Perform where arrythmia is considered

Imaging

Consider in the following circumstances:

- evidence of trauma

- focal seizure

- children requiring 3rd line agent

- children

<6 months

- signs of elevated ICP

- new focal signs or symptoms suggestive of stroke

- bleeding disorder / anticoagulation

- child has not returned to baseline or has persistent neurological signs once the postictal phase and the effect of any medication has passed

Avoid CT in children with established epilepsy after a typical seizure, unless there are other indications

EEG

- Rarely required in the acute setting

- Not routine after a first seizure. Should be considered if the child is

<12 months or has a known genetic condition

- Self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (SeLECTS) (also known as benign focal epilepsy of childhood (BFEC), childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (CECTS) or benign rolandic epilepsy) and idiopathic generalised epilepsy (IGE)

are the most common causes of afebrile seizures in children. Diagnosis needs EEG to confirm. SeLECTS and IGE may not require treatment, so EEG confirmation is usually not urgent. An EEG should generally be performed if a child has a second

seizure. A positive diagnosis can avoid the need for neuroimaging

Consider consultation with local paediatric team when

- Children

<12 months

- Suspected infantile spasms

- Prolonged seizures

- Incomplete recovery

- Intracranial pathology

- Meningoencephalitis

- Focal seizures or post ictal findings

- Recurrent seizures without a diagnosis of epilepsy

- Frequent/uncontrolled seizures in a child with known epilepsy

- Developmental delay

- Existing comorbidities

- Concern for non-accidental injury

Consider admission for observation in children

<12 months

Consider transfer to tertiary centre when

Children anticipated to require ICU level care (cardiorespiratory compromise)

For emergency advice and paediatric or neonatal ICU transfers, see Retrieval Services.

Consider discharge when

In older children, when the child is back to baseline function with no red flags on history or examination

All families should receive education prior to discharge which includes:

- explanation of risk of recurrence

- seizure safety advice

- seizure first aid and management plan

- advise parents to video events if safe to do so and keep a record

- provide written information

- consider need for emergency medication (buccal midazolam)

- advice regarding driving in older children of driving age

Follow-up after a first afebrile seizure

- All children who have a first afebrile seizure should have medical follow up

- EEG is not routinely performed after a first afebrile seizure but should be considered (child

<12 months or has a known genetic condition)

Parent information sheet

Seizures - safety issues and how to help

Epilepsy

Midazolam for seizures

Electroencephalography

PENNSW First seizure pack and video

Last updated June 2025

Reference list

- AMH Children's dosing companion. https://childrens.amh.net.au.acs.hcn.com.au/ (viewed October 2024).

- Chamberlain JM, et al. Neurological Emergencies Treatment Trials; Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network investigators. Efficacy of levetiracetam, fosphenytoin, and valproate for established status epilepticus by age group

(ESETT): a double-blind, responsive-adaptive, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020 Apr 11;395(10231):1217-1224.

- Dalziel S et al. Levetiracetam versus phenytoin for second-line treatment of convulsive status epilepticus in children (ConSEPT): an open-label, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2019. 393 (10186), p2135-2145.

- Kapur J, et al. NETT and PECARN Investigators. Randomized Trial of Three Anticonvulsant Medications for Status Epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 2019 Nov 28;381(22):2103-2113.

- Kids Health WA, Princess Margaret Hospital for Children. Emergency Department Guideline: Status Epilepticus. October 2017. https://kidshealthwa.com/api/pdf/645 (viewed October 2024).

- Lagorio I, et al. Paroxysmal Nonepileptic Events in Children A Video Gallery and a Guide for Differential Diagnosis. Neurology: Clinical Practice. 2022. 12 (4), p 320-327.

- Lyttle M et al. Levetiracetam versus phenytoin for second-line treatment of paediatric convulsive status epilepticus (EcLiPSE): a multicentre, open-label, randomised trial. The Lancet. 2019. 393 (10186), p2125-2134.

- NICE guideline [NG217]. Epilepsies in children, young people and adults. Published: 27 April 2022. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng217 (viewed October 2024).

- Paediatric Epilepsy Network NSW (PENNSW). First seizure e-learning resource. https://pennsw.schn.health.nsw.gov.au/clinicians/resources/e-learning (viewed October 2024).

- Paediatric Epilepsy Network NSW (PENNSW). Seizures and epilepsy factsheet. https://www.schn.health.nsw.gov.au/seizures-and-epilepsy-factsheet (viewed

October 2024).

- Paediatric Epilepsy Network NSW (PENNSW). First seizure pack and video. http://www.pennsw.org.au/families/resources/first-seizure-pack-and-video (viewed October 2024).

- Queensland Paediatric Emergency Care (QPEC) Queensland Paediatric Clinical Guidelines (QPCG). Status Epilepticus -- Emergency Management in Children. Retrieved from https://www.childrens.health.qld.gov.au/for-health-professionals/queensland-paediatric-emergency-care-qpec/queensland-paediatric-clinical-guidelines/status-epilepticus (viewed June 2024)

- SA Health. South Australian Paediatric Clinical Practice Guidelines. Seizures in children. https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/80c8b2004329b65c8219ee8bf287c74e/Seizures+in+Children_Paed_v4_1.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CACHEID=ROOTWORKSPACE-80c8b2004329b65c8219ee8bf287c74e-p4ci8Xc (viewed October 2024).

- Smith eds. Advanced Paediatric Life Support7th Edition, Wiley Blackwell, 2024.

- Specchio N, et al. "International League Against Epilepsy classification and definition of epilepsy syndromes with onset in childhood: Position paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions." Epilepsia 63.6 (2022):

1398-1442.

- Spooner C, et al. Starship Child Health. Seizures -- status epilepticus. December 2021. https://starship.org.nz/guidelines/convulsions-status-epilepticus (viewed October 2024).

- The Sydney Children's Hospitals Network. Guideline No 2014-9103 v2, Guideline: Seizures and status epilepticus management. July 2021. https://resources.schn.health.nsw.gov.au/policies/policies/pdf/2014-9103.pdf (viewed October 2024).

- The Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne. Paediatric injectable guidelines online. https://pig.rch.org.au/monographs/ (viewed October 2024).

- Williams G, et al. Starship Child Health. Seizures -- afebrile. September 2018. https://starship.org.nz/guidelines/seizures-afebrile (viewed October 2024).

- Western Australia Child and Adolescent Health Service & Perth Children's Hospital. Status epilepticus. July 2022. https://pch.health.wa.gov.au/for-health-professionals/emergency-department-guidelines/status-epilepticus (viewed October 2024).

- Western Australia Child and Adolescent Health Service & Perth Children's Hospital. Seizure -- first presentation. https://pch.health.wa.gov.au/For-health-professionals/Emergency-Department-Guidelines/Seizure-First-presentation (viewed October 2024).