Burn injuries

see also:

Key points

-

Burn injuries should be managed

as a trauma case requiring primary and secondary survey

-

Accurate Total Body Surface Area

(TBSA) estimation is essential for fluid resuscitation decision making – it

does not include epidermal burn

-

Optimal fluid

resuscitation is crucial – inadequate resuscitation contributes to

intravascular hypovolaemia and organ failure; excessive resuscitation

contributes to fluid creep with extension of the burn wound and systemic oedema

causing cardiorespiratory compromise, intra-abdominal and limb compartment

syndrome

-

Managing pain and preventing

complications are an important part of burn assessment and patient care

-

Close supervision of children at

all times will help prevent burns

-

Some minor burns will be able to

be managed at non- Paediatric

Burn Unit

-

Burn management requires

multidisciplinary approach including

psychosocial care which addresses the significant impact a burn can have on a

child and their family

Background

Burns

are common in children. Burns range from minor wounds that can be managed in an

outpatient setting to moderate wounds,

requiring transfer to Paediatric Burns Unit and surgical management,

through to major wounds with associated traumatic injuries requiring retrieval

to Paediatric Intensive Care and Burns Unit.

Scald burns in young children are the most common type of burn. Most

burns are mild and can be managed in a community setting, however major burns

require prompt and h

Burns in children are different to those in adults due to their

differences in their physical attributes, developmental abilities and emotional

maturity.

An accurate assessment of a burn depth is difficult, especially

early post injury. All burn injuries should be considered part of a trauma assessment,

and non-accidental inflicted injury should be considered.

Epidemiology

Burns are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in

children, and a common cause for hospital admission.

Most burns occur in the home, predominantly in the kitchen. Most burns

are not very severe and are small; <10% total body surface area (TBSA). Most

hospitalisations are short (<1 day), though many burns require community

care and some for prolonged periods of time.

Globally,

nearly 96, 000 children under the age of 20 were fatally injured as a result of

a fire-related burn in 2004[i]. Within all countries burn risk correlated with

socioeconomic status. Regional

differences in burns exist; in

2018 children under 5 years

of age in African Region have 2 times incidence of burn deaths than their

worldwide counterparts; boys under 5 years

of age from low-middle income countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Region are

nearly twice as likely to die from burns as similar boys from

the European Region; burn injuries requiring medical care is almost 20 times

higher in Western Pacific Region compares to the Region of the Americas[ii].

In the developing world open cooking fires are a major source of

burns; commonly hand burns. Burn injuries to hands are particularly disabling due

to impaired functionality and lack of adequate rehabilitation/assistance

devices in the developing world - even a small hand burn can affect an

individual’s ability to perform activities of daily living independently and

perform physical labour for a family’s livelihood.

The death rate in low-income and middle-income countries is eleven

times higher than that in high-income countries – 4.3 per 100 000 as compared

to 0.4 per 100 000[i].

The type and cause of paediatric burns are related to the age and

developmental stage of the child. Young children are most likely to incur a burn

injury: 70% paediatric burns occur in <5 year old children. Infants have the

highest death rates. The highest rates of hospital admission are of children

<4 years old which correlates

Males are over represented in all age groups for burns and the

gender imbalance increases with age. From 10-14 years of age males have a sharp

increase in burn injuries from exposure to highly flammable liquid (eg petrol).

In Australia, burn

and scald injuries are especially high for infants and children <4 years of

age. Hot drinks, food, fats and

cooking oils cause more than half of the scalds in this group, with face,

trunk and arm burns being the most common sites of injury. Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander people have higher rates of burns in all ages

compared to other Australians, and whilst

all Australians have the highest rate of burns in less than 4 year olds

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children of this age are more likely than

other Australians to be burned (174 cases per 100,000 compared

to 45 cases per 100,000

population)[iv].

Other

risk factors for paediatric burns include poverty, overcrowding, lack of

safety measures or adequate parental supervision including young girls being

given a household role of cooking. Children with some underlying medical conditions are also at

increased risk of burns such as epilepsy and physical or cognitive

disabilities. Children

are at risk of burns from neglect and inflicted burns as child abuse.

Pathophysiology

A burn is a thermal injury

resulting in a wound characterised by an inflammatory reaction leading

initially to local oedema from increased vascular permeability, vasodilation

and extravascular osmotic activity. It is caused by direct effect of the burn

agent on microvasculature and resultant chemical

inflammatory mediators.

A burn is an injury with both

local and systemic responses. There are three major types of burn: thermal,

electrical and chemical. Changes in tissue after the burn

trauma are very important. In large burns fluid loss from damaged tissue causes

decreased plasma and increased haematocrit with decreased cardiac output which

contributes to widespread cellular hypoperfusion resulting in multisystem

damage.

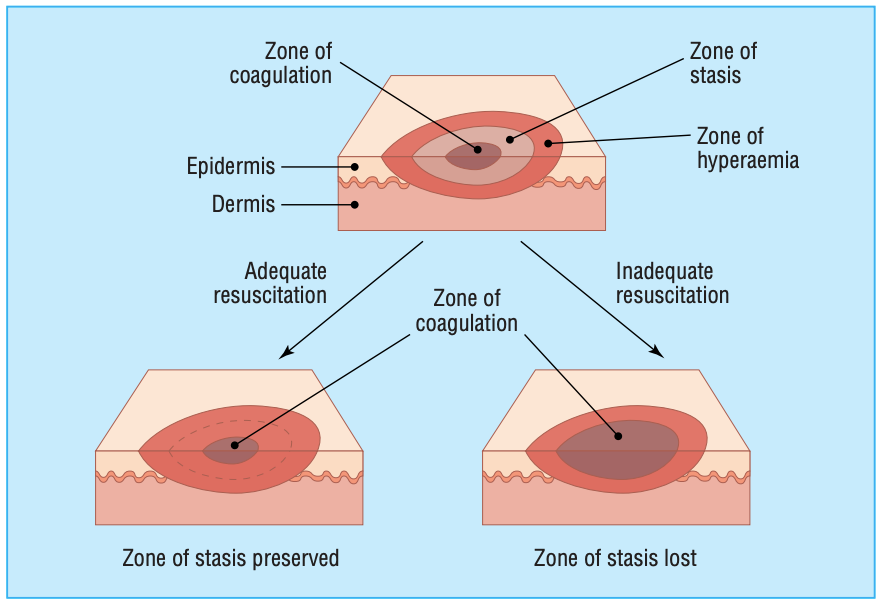

Local response

Zone

of coagulation – this is the primary site

of injury and the site of maximum damage. This zone comprises irreversible

tissue loss due to exposure to heat, electricity and/or chemicals.

Zone

of stasis – this surrounding zone has decreased

tissue perfusion and is a penumbra of potentially salvageable tissue. Good quality

first aid and burn resuscitation aims to reverse ischaemia and minimise the size

of this zone. Risks to increasing size include increased depth of burn, prolonged

hypotension, infection and oedema. This zone changes making initial burn

assessment difficult. The full extent of injury is only apparent after several

days.

Zone

of hyperaemia – this outer zone comprises

and area with increased perfusion and will

recover unless there is an additional insult.

Skin loss decreases the

body’s ability to preserve heat and water and act as a barrier to prevent

infection. Resuscitation and treatment aim to correct these consequences.

Figure 1: Jackson's Burn Wound Model, 1947. (Reproduced

with permission: Figure

2 Hettiaratchy

S, Dziewulski P. ABC of burns: pathophysiology and types of burns British Medical

Journal.

2004;328(7453):1427–1429Ds).

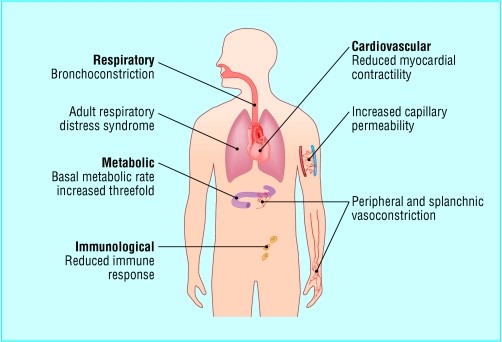

Systemic response

Once TBSA >30% a systemic

inflammatory response will occur.

The renal and hepatic systems are susceptible to dysfunction due to

resultant fluid and protein loss and a decreased blood volume. In

major burns the fluid state of the patient must be carefully managed. Adequate

and timely fluid resuscitation due to excess losses from the burn are crucial

in curbing the extent of systemic dysfunction from this mechanism. Similarly,

over resuscitation with excess fluid can have detrimental effects on

cardiorespiratory function and contribute to compartment syndrome in the limbs

and abdominal cavity.

A widespread inflammatory response also occurs as the result of a burn injury

with release of catecholamines, vasoactive mediators and inflammatory markers

which can trigger a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) resulting in

multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS).

Figure 2: Systemic response to burns

Reproduced with

permission. (Figure 3 Hettiaratchy S, Dziewulski P. ABC of burns:

pathophysiology and types of burns British Medical Journal.

2004;328(7453):1427–1429[v]).

SIRS also contributes to

immunosuppression rendering a patient more susceptible to bacterial infection

and sepsis. The systemic

response worsens initial organ damage caused by shock and reduces the body’s

ability to fight infection; this leads to an increased risk of sepsis which

further triggers inflammation, immunoparesis and infection.

Following a burn injury, a hypermetabolic state ensues where catabolism

increases and anabolism decreases resulting in loss of muscle and bone mineral

density. Wound healing may also be affected. This hypermetabolic state is

sustained despite wound closure. Protein breakdown continues 6 – 9 months after

the initial burn making nutritional support to sustain lean body mass and

promote wound healing of crucial import. Bone growth can be delayed for 2 years

after a burn injury in children.

How children are different to adults

Children have thinner skin

than adults, therefore the time to burn, or the

energy required to cause a burn is less. This means that a

burn agent at any given temperature, will

cause a deeper burn, at a faster rate,

in a child compared to an adult.

Young children are at risk of hypothermia, especially during

initial cooling of the burn and from increased evaporative loss due to their

larger surface area to body mass ratio.

Children have an increased blood volume relative to their mass

therefore fluid resuscitation needs to accommodate for this: large volumes per

unit body weight are required compared to adults. Small children are more

likely to become hypoglycaemic and

The risk of airway compromise in children following inhalation

injury is greater due to a smaller airway opening and greater risk of closure

from oedema.

The systemic inflammatory response in children tends to be

stronger with more vulnerability to their effects, including am increased

susceptibility to the resultant hypermetabolic state.

As children are still growing their need for skin growth and

elasticity to accommodate this growth complicate wound and scar management.

Assessment: History of burn

Time of

injury

Mechanism of injury,

including circumstance for specific pattern of burn

- Scald: estimate temperature and ask about the nature of

the liquid

- Recently boiled water?: likely to be close to 100 degrees Celsius,

- Hot drink with milk?: likely to be a cooler than recently boiled water

- A solute in the liquid?: eg boiled rice – raises the

temperature of liquid

- Viscous liquid? more viscous fluids result in more severe burns as they remain in contact with skin for longer

- Common causes include scalds from hot drinks(tea/coffee), kettles, bath, noodles

- Contact: estimated temperature and nature of the surface

- Common causes include irons, hair straighteners, exhausts, campfires,

metal clips on car seats

- Radiant:

- Common causes include sunburn - this may be associated with neglect. Some burns sustained during house fires or bush fires can be due to radiant heat.

- Friction:

- Common causes include falling on, or touching, moving treadmills, or road rash after a motor vehicle crash

- Flame / explosion:

- ask about the product

that burned/exploded: to predict temperature

and predict secondary effects

- ask about the location where the patient was exposed: indoor flame injuries are more likely

associated with inhalation injury as compared to those in open spaces; indoor explosions may be associated with greater traumatic injuries

- ask about the duration

of exposure: to predict extent of burn

- Common causes include flash burns after pouring accelerants (kerosene, petrol) onto BBQ's / bonfires, as well as in house fires

- Electrical:

- Low voltage (<1000V - typically domestic), high voltage (>1000V - often industrial) and lightening have different patterns of injury and complications

- Type

of current: alternating current

(AC) or direct current (DC). DC

typically provides a single convulsion or contraction usually propelling person

away from source, whereas AC causes repeated

convulsions and cardiac arrhythmias such as VF and is

considered more dangerous; a

larger magnitude of DC is required to cause injury than AC

- Was there

a flash or arcing: more likely to cover a

large surface area and be more superficial,

time and duration of contact: to predict severity of burn

- Common cause include young children chewing on electrical cords

- Chemical:

- ask about the type of product: to

predict extent of burn and secondary effects (alkali vs acid burns)

-

look at clothing for stain colour

- Cold:

- direct contact with cold surface or exposure

(frostbite)

- Inhalation:

- common causes include inhalation of hot gases during a house fire, or flame burns to the face. May be of greater consequence if they have occurred

in enclosed space

First aid

- Time started (was it within 3 hours)

- Agents used - cool running water vs less effective agents (standing water, cold compress, ice, home remedies)

- Duration - was it at least 20mins of cool running water?

- If clothes and jewelry were removed

- Decontamination method (for chemical exposure)

Any

circumstances to implicate co-existing non-burn injuries

Any

circumstances to implicate non-accidental injury or vulnerable child

Tetanus

status

Assessment: Primary survey

Like all traumas,

paediatric burn assessments require an initial

primary survey with the aim of identifying and managing immediate life threats:

do not be distracted by the burn injury until all

immediate life threats have been addressed. The list below indicates some of the key examination findings to look for during the primary survey. These findings may signal the presence of an immediate life threat requiring management during the primary survey. Do not neglect to apply personal protective equipment (PPE) which is especially

important to protect health care workers where the patient

has a chemical burn.

Examination

- Signs of

airway burn/inhalation injury: stridor, hoarseness, black sputum or

respiratory distress, singed nasal hairs or facial swelling

- Sign of

oropharyngeal burn: presence of soot in mouth, intraoral oedema and

erythema

- Significant

neck burn

Management

- If suspicion of

airway burns apply high flow oxygen

- Protect the cervical spine with

cervical spine motion restriction if there is associated trauma

Breathing

Examination

- Signs of inhalation injury as above

- Full thickness and/or circumferential

chest burns

- Tension pneumothorax

secondary to an explosion / associated trauma

Management

Circulation

Examination

- If early

shock is present, consider causes other than the burn

- For

circumferential burns check peripheral perfusion (and

Management

- IV or IO access (preferably 2 points of access)

- Consider IV fluid resuscitation

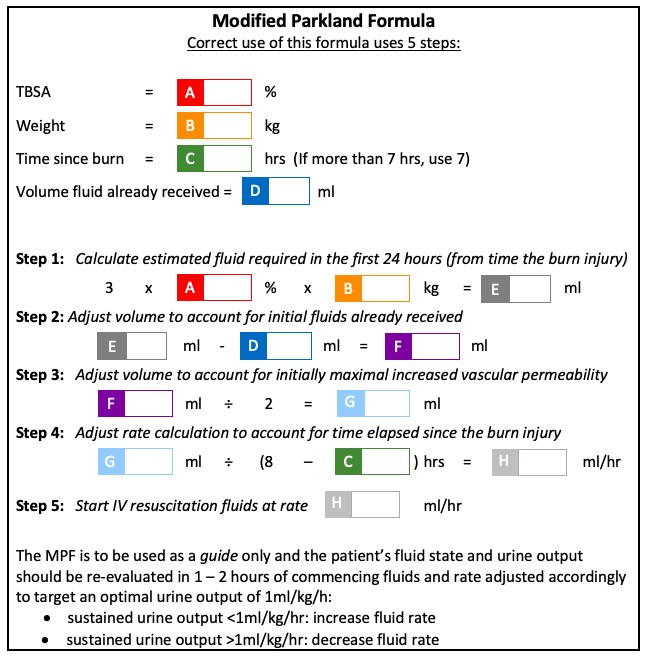

Resuscitative Fluid management in burns >10% TBSA

- This is required to compensate

for excess fluid losses in the first 24 hours after burn

- Calculate

requirements from time of the burn, not time of presentation

- Calculate

fluid volume using Modified Parkland Formula (MPF) (below)

- Hartmann’s

Solution is the fluid of choice - if unavailable, use 0.9% N saline

- Glucose in maintenance

fluid is required for children <20kgs

Patients with delayed fluid resuscitation, electrical conduction

injury and inhalation injury have higher fluid requirements. Discuss with

specialist team.

For burns >10% TBSA

- In dwelling catheter (IDC) is

recommended to monitor urine output

- Nasogastric tube (NGT) is recommended with

nil by mouth state to manage an initial gastroparesis associated with burns and

later to ensure adequate caloric intake in the coming days

Fluid creep

Fluid creep refers to excessive fluid administration to

patients with burns. Adequate fluid resuscitation is a crucial part of managing

children with major burns; if provided early it restores intravascular volume

and maintains tissue perfusion both to the burn wound which avoids extension of

the injury into the zone of stasis, and to the body which evades more

widespread complications such as renal failure and reduces mortality[iv].

The Modified Parkland formula above should be used as an

initial guide to fluid resuscitation but the ongoing fluid replacement in a

child with a major burn must include regular and in-depth fluid assessment

beyond the urine output alone. If a child with a major burn is overhydrated it

can lead to the development of systemic interstitial oedema which independently

cause complications such as limb ischaemia from increased limb compartment

pressures, renal failure from intra-abdominal compartment syndrome and

respiratory failure from airway swelling and trauma.

To avoid fluid creep, avoid over estimation of TBSA,

include all resuscitation fluids received by patient when calculating the

appropriate resuscitation volume. If the fluid volumes appear greater than the

predicted requirements from the modified Parkland formula alternative causes

should be sought and managed. A fluid assessment of a patient with major burns

includes not only the urine output but clinical fluid examination, biochemical

markers, ventilatory parameters and end organ perfusion markers.

Disability

- Neurological

state: GCS and pupillary response

- If suspicion of carbon monoxide poisoning

apply high flow oxygen

- Neurovascular

status if limb involved (asses with doppler ultrasound if necessary) –

requires elevation of the effected limb and hourly neurovascular

observations

Exposure

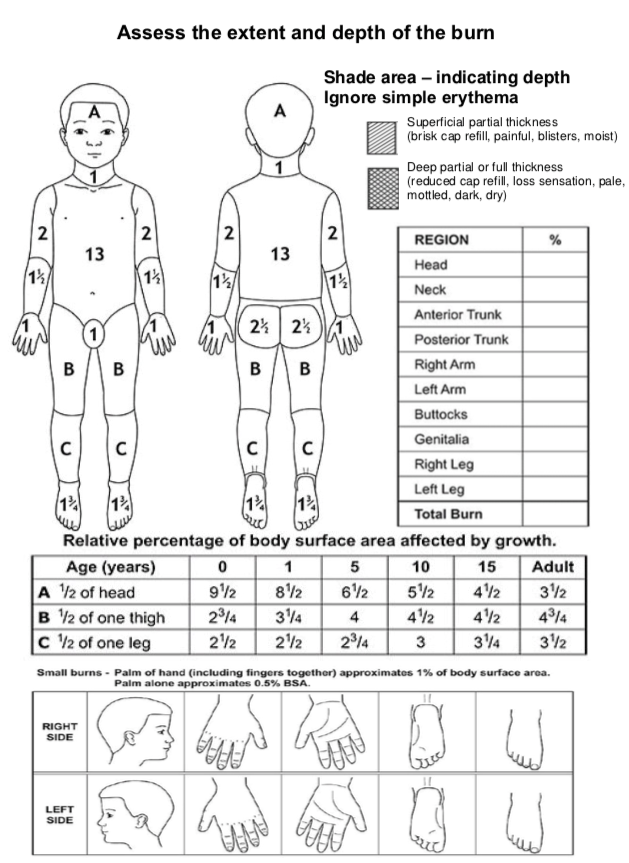

Fully expose the patient in order to assess the extent of injury in terms of:

- the percentage of Total Body Surface Area (TBSA) that is affected by the burn and

- the burn depth

Check the patient's temperature (it is easy for small children to become hypothermic after cooling). The principle is to keep the patient warm, but the burn cool. The 20 mins of cool running water during first aid can be split into shorter sessions, with warming of the patient in between, as long as all the cooling occurs within the first 3 hours.

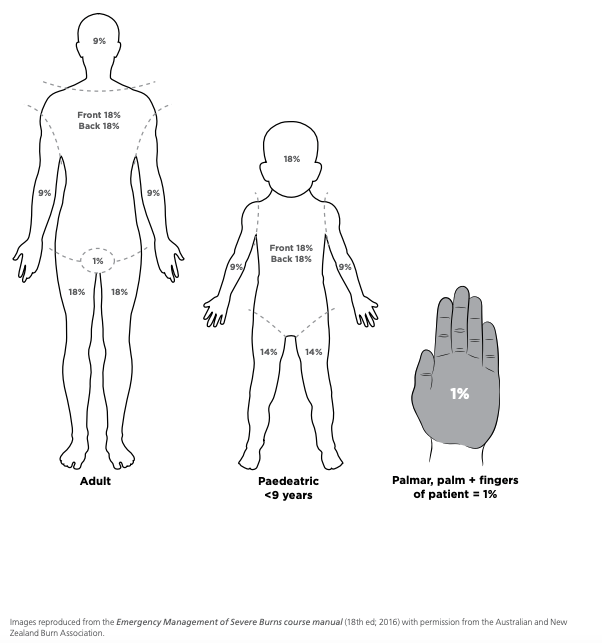

Assessment of TBSA

- Expose whole

body - remove clothing and log roll to visualise posterior surfaces

- Keep patient

warm

- Estimate burn

area with the Lund & Browder Chart

- Do NOT include area with epidermal burn (erythema only)

- TBSA

determines need and volume of fluid resuscitation, hospital admission and

transfer to Paediatric Burns Unit

Reproduced

with permission. (Appendix

1. CHQ-GDL-06003

– Management of a paediatric burn patient within the Pegg Leditschke Children’s

Burns Centre. Children’s

Health Queensland Hospital and Health Service[vii]).

Assessment of burn depth

- Burns are

dynamic wounds: it is difficult to accurately estimate the true depth and

extent of the wound in the first 48-72 hours

- Burns are

described as epidermal, dermal (superficial/mid/deep) and full thickness

- Speed of

capillary refill is a good indicator of burn depth, although burn wound

evolution results in increasing depth therefore examination can change over

time

-

Most burn wounds are not a homogenous depth

|

Classification

|

Depth

|

Colour

|

Blisters

|

Capillary Refill

|

Sensation

|

|

SUPERFICIAL

|

Epidermal

|

Red

|

No

|

Brisk

|

Present

|

|

Superficial Dermal

|

Pale Pink

|

Present

|

Brisk

|

Painful

|

|

Mid Dermal

|

Dark Pink

|

Present

|

Sluggish

|

+/-

|

|

DEEP

|

Deep Dermal

|

Blotchy Red

|

+/-

|

Absent

|

Absent

|

|

Full

Thickness

|

White

|

No

|

Absent

|

Absent

|

Assessment: Other considerations

Consider

co-existing injuries

Especially in motor vehicle crashes, blasts/explosions, electrical

injuries or jumps/falls from significant heights.

Consider

alternate diagnosis: scald burn mimics

- Staphylococcal

Scalded Skin Syndrome

- Blistering

distal dactylitis – caused by group A strep

- Stevens

Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis – follows medication use

- Hair tourniquet – distal erythema and swelling can mimic a

peripheral burn

Consider non-accidental injury (see

below)

Burn Wound Management

Like all traumas paediatric burn injuries require recognition

and management of all injuries following the primary and secondary survey.

Acute

management of superficial burns with

erythema only

- Can be treated without dressing

- Infants who show a tendency to blister or scratch,

a protective, low-adherent dressing with crepe bandage may be helpful.

Acute

management of minor burns (isolated, <10% TBSA)

- Analgesia may be required for assessment and

initial dressings

- Consider sling and splinting for more

extensive upper limb burns

- Dressings that can remain in situ for 3-7 days

are recommended for partial thickness burns

- The depth of a partial thickness burn may only

be declared after 7-10 days

- De-roof/debride if blister is large or

overlying a joint

Acute

Management of major burns (>10% TBSA) or complex burns

FACADE

=

First aid, Analgesia, Clean, Assess, Dress, Elevate

First

aid

- Remove jewelry and clothing in contact with burn source

- Do not remove bitumen stuck to a burn

- Cool affected area as soon as possible

(within 3 hours from time of burn) for a total of 20 minutes with cool running

water

- If cool running water is unavailable,

other options include: frequently changed cold water compresses/towels,

immersion in a basin, irrigation via an open giving set

- Never apply ice and avoid use of

hydrogel burn products

- Do not use butter, sugar, oil,

toothpaste, potato, egg white or other traditional remedies

- Prevent hypothermia: cool the burn not

the child

- Remove wet clothes/dressings after

initial cooling

- Try to keep child otherwise warm

- Cover the wound and the child after

assessment

- When possible, warm the intravenous

fluids and the room

- Cover burn with plastic cling film lengthways

along the burn (do not wrap circumferentially) - this helps maintain burn wound

moisture and protect exposed nerve endings which contributes to pain management

- Do not apply plastic cling film to

face (use paraffin ointment)

- Do not apply plastic cling film to a

chemical burn

- Discuss Chemical burn decontamination

with Poisons Information (Tel: 131126)

- Appropriately consented photos of

burns should accompany a referral if possible

Analgesia

- Burns are painful and often require strong

analgesia: appropriate initial choices include intranasal fentanyl or IV

morphine

- Utilise

multimodal analgesia including cooling, cling film, parental presence/support

to alleviate anxiety and distraction

- Analgesia is required

especially during cooling, dressing and mobilisation

Clean

- Limit debridement to wiping away

clearly loose/blistered skin

- De-roof

blister (with moist gauze or forceps and scissors) if

>5mm or crossing joints

- Clean

burn wound and surrounding surface with saline or water or 0.1% Aqueous

Chlorhexidine on gauze (flannel if no gauze)

- Pat dry

Assess

- Assessment

of burn injury TBSA and depth as above

- Take

photos with appropriate consent

Dress

- Apply appropriate occlusive non-adherent dressing; if these

products are not available, refer to local Burns service for alternative

options

If

there is anticipated delay or time until definitive care, consider use of

multiple layer non-adhesive paraffin antiseptic dressing.

|

Location

|

Depth

|

Dressing

|

|

Facial

and perineal burns

|

Epidermal

or superficial dermal

|

Apply

white soft paraffin twice daily after cleaning face

Chloramphenicol

ointment to eye and ear burns

Perineal

burns are at risk of contamination – after bowel action, area should be

cleaned with soapy solution; consider catheterisation; 4% chlorhexidine skin

wash

|

|

Mid

or deep dermal

|

Consider

silver-impregnated dressing (discuss with Burns service)

|

|

Other

body regions

|

Epidermal

|

May

not require dressing

Consider

covering with protective, low-adherent dressing for comfort

|

|

Mid

or deep dermal

|

Dressing product used depends on the expected

duration required before removal or wound review

In general:

- for small, superficial partial thickness burn

wounds use a low adherent dressing then crepe bandage/tape

- for more extensive or deeper partial thickness

burn wounds use a low adherent silver dressing then crepe bandage.

|

Elevate

- Elevate

burn by positioning and adjuncts (pillows, towels, slings)

- Elevation

aids management of oedema to minimise poor tissue perfusion and improve wound

healing

- Do

not apply tight circumferential bandages

- Elastic

compression is helpful (Tubigrip)

- Encourage

functional activity of effected body part

Operative

management

Superficial

wounds should heal by regeneration within 2 weeks and need only cleaning,

dressing and review to optimise healing. If a burn has not healed within 2

weeks it should be referred for assessment and may require surgery.

Deep

partial thickness or full thickness burns are likely to require operative

management which includes excision of the deep burn and skin grafting within

5-10 days to expedite healing and minimise scarring. Sometimes artificial

dermis is used as a bridge to skin grafting. Skin grafts can be autografts or allografts.

Grafting consists of 4 steps

- The removal of injured tissue

- Selection of a donor site, an area from

which healthy skin is removed and used as cover for the cleaned burned

area

- Harvesting, where the graft is removed

from the donor site

- Placing and securing the skin graft over

the surgically-cleaned wound so it can heal

For large burns multiple operations may be

required to complete the grafting process.

Investigations

|

Major burn

(≥10% TBSA)

|

Haemoglobin,

electrolytes, BGL, group and hold, VBG

|

|

Suspected

inhalation injury

|

ABG for

carbon monoxide, lactate, cyanide level

|

|

Electrical

burn

|

Cardiac

monitoring, urine myoglobin

|

Special considerations

Circumferential

deep burn

(deep dermal or full thickness)

Elevate part of limb distal to

burn to minimise swelling and oedema. Assess and monitor for neurovascular compromise of tissue distal

to the burn; escharotomy may be

required.

Limb

burns

Elevate the limb and monitor perfusion distal to burn.

Hand

burn

Hand burns in children are common

due to the inquisitive nature of children and their developing motor skills.

Assessment and management of hand burns in children are as above. Special priority

must be given to early active rehabilitation to optimise hand function. See

Rehabilitation below.

Treadmill

injury

Exercise equipment is becoming commonplace in homes. Children

should not have access to treadmills at any time: switch off power at wall and

unplug, keep behind closed toddler gate or locked door. A friction injury

caused by a treadmill is a type of burn, which should be assessed and treated

as a burn. Friction injuries from treadmills are commonly on children’s hands

and cause serious burns often requiring surgical intervention and lengthy

rehabilitation.

Head

and neck burns

Nurse head up to reduce swelling and oedema.

Ocular

burns

Signs of ocular burns include

blepharospasm, tearing and conjunctivitis. All facial burns should have

ophthalmological assessment including visual acuity, external ocular exam and Fluorescein

2% eye drops to assess for corneal damage. Full thickness facial burns propose

high risk of ocular damage.

Both thermal and

chemical corneal burns threaten vision; alkalis penetrate deeper and have greater

potential for serious and delayed burns.

Treat all ocular chemical burns with

copious irrigation using 0.9% NaCl as soon as possible. Ensure the

unaffected eye is uppermost during irrigation of effected eye to avoid further

contamination. Use topical anaesthetic on effected eye for

analgesia and to aid tolerance of irrigation.

- Irrigate until all chemical/alkali washed out (test

with pH strip prior and post)

- Up to 1 hour with acidic contamination

- Up to 2 hours with alkaline contamination

Use topical Chloramphenicol to prevent

secondary infection.

Urgent paediatric ophthalmology review is

required to for:

- All

ocular burns

- Full

thickness eye lid burns

- Facial

burns with inability to close eyelids

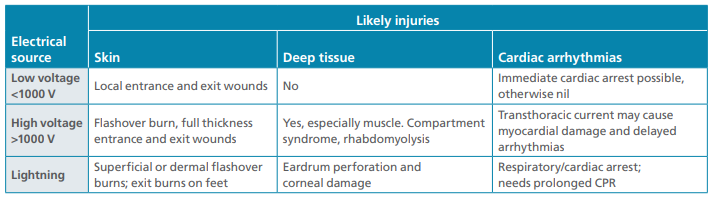

Electrical

injuries

Degree of injury is related to the voltage of the electrical

source. Electrical injuries can be associated with other injuries: consider

spinal precautions. Electrical injuries can also cause cardiac dysrhythmias -

consider 24 hours ECG monitoring. Monitor and manage elevated CK, urine haemoglobin/myoglobin

and haemochromogen. Monitor for

compartment syndrome.

Reproduced

with permission. Clinical Guideline, Statewide

Burn Injury Service – NSW Burns transfer guidelines (4th edition) Page 12

Electrical burns: table Overview of electrical injuries © Copyright -

Agency for Clinical Innovation 2020[viii]

Electrical

injury: labial artery erosion

Children can suck on or chew through power cords, or can chew on

damaged/frayed power cords, resulting in an electrical burn. Even low voltage

electrical burns can be serious causing deep injury with muscle tendon and

vessel involvement. Electrical burns occurring at the edge of the mouth can be

associated with acute or delayed (up to 21 days) labial artery involvement and

significant haemorrhage.

Chemical

burns

Chemical burns are

caused by caustic agents:

- Acids cause coagulative necrosis

of the superficial tissue eg toilet cleaner

- Bases cause liquefactive necrosis

and have a higher capacity for injury, including deep to the initial wound and

ongoing injury process despite removal of base eg laundry detergent

- Organic solutions cause injury by

dissolving the lipid membrane

- Inorganic solutions cause injury

by tissue denaturation

First aid of chemical burns with

irrigation of cool running water is extremely important and is often forgotten. Personal

protective equipment for first aid givers should be worn (gloves, mask, gown,

eye protection. Ensure contaminated clothing is removed and brush any powdered

agent off skin onto a collection sheet to be disposed of appropriately.

Irrigate from the top of the wound down to the floor with

appropriate drainage so contaminated water does not cause further injury.

Consider systemic symptoms from metabolic and electrolyte

disturbance from absorbed agent.

Chemical burn: oesophageal injury

Many harmful

agents are found in everyday households eg toilet cleaner, bathroom cleaner,

hair products, laundry and dishwasher detergents, batteries, drain and oven

cleaners. Ingestion of caustic agents can lead to oesophageal burns, strictures

and perforation. Children with significant injury may have no-mild symptoms

only. Symptoms include dysphagia, drooling, chest/abdominal pain, refusal to

eat, respiratory compromise. The injury tends to worsen over time.

Tetanus

prone wounds

Consider if prophylaxis with vaccination or tetanus immunoglobulin

is required.

Inhalation

injury

These occur with flame burns in

enclosed spaces. Direct inspection of the oropharynx should be performed on

arrival and consideration of early intubation by an experienced airway specialist.

Inhaled smoke is cool upon

reaching the lungs but products of combustion are irritating leading to

bronchospasm, inflammation and swelling. This predisposes an individual to

atelectasis and pneumonia, and can be worse in asthmatics. Patients may require

non-invasive positive pressure ventilation or invasive ventilation and airway

toileting.

Carbon monoxide and cyanide

poisoning

If suspicion of associated Carbon

monoxide (CO) poisoning or cyanide poisoning liaise early with Paediatric Burn

Unit, Critical Care and Poisons Information (Tel: 131126).

Carbon monoxide is a toxic gas

inhaled during a fire, such as a patient enclosed in a house fire. Carbon

monoxide binds very strongly to haemoglobin and intracellular proteins

contributing to intracellular and extracellular hypoxia. Toxicity is dose

dependant involving no or few symptoms through to cardiovascular compromise

with seizures and death[ix].

Symptoms include:

- Gastrointestinal: nausea,

- Respiratory: dyspnoea, respiratory failure

- Cardiac: syncope, cardiovascular compromise

with myocardial ischaemia

- Neurological: dizziness, vertigo, ataxia,

visual disturbances, headache, confusion and decreased conscious, seizures

Pulse oximetry cannot differentiate between haemoglobin and

carboxyhaemaglobin so will not read low even when a patient is hypoxic. Blood

gas will show metabolic acidosis and raised carboxyhaemaglobin. These patients

require 100% oxygen and may require ventilation. Unborn foetus can be affected

by toxicity: specifically discuss care of pregnant women with specialist teams.

Cyanide

is a potentially lethal toxic poison that is produced in gaseous form from burning natural and synthetic fibres such as plastics and

wools such as occurs in in domestic/industrial fires. Cyanide poisoning occurs

from inhalation of this gas and often occurs with carbon monoxide poisoning. Toxicity

is dose dependant and incudes multisystem involvement[ii].

Initial symptoms include:

- Gastrointestinal: nausea, vomiting

- Respiratory: tachypnoea, dyspnoea

- Cardiac: tachycardia, hypertension

- Neurological: headache, decreased conscious

state, seizures

More severe symptoms include end organ damage

form anaerobic metabolism with associated hypotension, bradycardia and

cardiovascular collapse, respiratory depression and reduced GCS.

Blood gas will show metabolic

acidosis with high lactate, serum level cyanide should be taken.

Treatment includes ABC resuscitation, high

flow oxygen and administration of antidote hydroxocobalamin then sodium thiosulfate.

Frostbite

Frostbite is a type of burn

injury to the skin and underlying tissues by freezing. It most commonly effects

the extremities and can be divided into superficial or deep. It can occur

through exposure to cold-weather conditions or direct contact with cold ice,

liquid or metal. Minor frostbite injuries can be managed with simple first aid

involving analgesia and rewarming followed by simple wound care. More serious

injuries may require review with a burns service for more intensive wound care

management.

Non-Accidental Injury

Non-accidental burn injuries can occur in the setting of neglect

or physical abuse. Inflicted burn injuries are under recognised; it is

difficult to estimate the incidence. They effect children of all ages and incur

significant mortality and morbidity[iii].

Concerning

features on history

- Inadequate supervision

- Delayed presentation

- Changing mechanism

- History that is incompatible with

age/development of child and injury

- Mechanism that is incompatible with

injury

Scalds are the most commonly inflicted burn injury. Certain

locations or patterns of burn are more suspicious for an abusive cause:

- Hands

- Feet

- Genitals

- Buttocks

Burns

concerning for inflicted injury

Submersion burns

- Circumferential

- Symmetrical

- Uniform depth

- No splash marks/satellite burns

- Buttocks, perineum, extremities

- Sparing on buttock cheeks “donut sign”

(held down on bath), in flexures (groin, knees) and abdominal creases (as trunk

is flexed forward when child tries to protect them self)

- Glove and stocking distribution for

limb submersion

Contact burn

- Very young child

- Patterned burn >1 lesion

- Cigarette burn: clustered, sharply

demarcated, ~1cm punched out, deep, circular, hands and feet

- Iron

- Lighter – classic “smiley face”

patterned burn

- Trunk or buttock

- Bilateral foot sole burns from being

held on hot pavement

What

to do if you are concerned a burn injury was caused by neglect or abuse

- Take clear photographs with consent

for the patient’s medical record ensuring you capture the edges of all burns

and presence/absence satellite lesions, clearly document age of the burn as

child protection can use burn healing to help ascertain the cause and timing of

the injury (consider image with tape measure if available for sizing)

- Report suspected abuse to Department

of Health and Human Services

- Consider a “scene investigation” – a

formal assessment of the scene of injury performed by Police or Child

Protection to provide valuable information regarding the environment where the

injury occurred

- Carefully assess the child for other

evidence of inflicted injury (bruising, fractures, abusive head trauma,

injuries from shaking/impact)

- Consider referral to local paediatric

forensic service

Consider consultation with local paediatric team when

- Suspected non accidental injury,

self-inflicted burns or assault

- Multiple co-morbidities

- Concern regarding social situation or

dressing compliance

Consider transfer to a Paediatric Burn Unit when

Child requiring care beyond

the comfort level of the hospital

Following burns:

- >10% TBSA

- All full thickness burns

- Special areas: face, ears, eyes, neck,

hands, feet, genitalia, perineum or a major joint, even if <10%

- Circumferential

- Chemical

- Electrical

- Associated with trauma and/or spinal cord

injury

- All inhalation/airway

- Children <12 months

Discharging a patient with a burn wound

Minor burns may be discharged at initial presentation and referred

to outpatient burns follow up of local service with 1-2 visits per week

initially.

Moderate or large burns or patients with multiple injuries will

have required in patient admission or transfer to a Paediatric Burns Unit and

may require Paediatric Intensive Care. As part of acute care – once discharged

will require multiple follow up appointments as an outpatient.

The ability of a family to provide adequate care for a child with

a burn and attend appointments should be taken into account when deciding the

child’s disposition. These include geographical isolation and concern for

social welfare of child; delayed presentation, suspicion of non-accidental

injury or concern family will not care for wound or attend appointments.

Follow up

Burns can

evolve over time. Consider a follow up within 3 days of initial presentation to

reassess depth, monitor healing and determine ongoing management. On

reassessment referral to Paediatric Burn Unit is necessary:

- Depth is unclear after 3 - 5 days

- Slow to heal – poor progression at 5-7 days

Post Acute Care of Burns

The type of care a child requires depends on the type, depth and

extent of burn, involvement of burn in special areas premorbid health,

additional injuries and psychosocial situation (eg concern of neglect or non-accidental

injury). A multidisciplinary team is required.

Burn

Dressings

The burn wound dressing will depend on the type and severity of

the burn wound.

Principles of burn wound management

- Relieve pain

- Maintain a moist wound environment

- Keep wound clean

- Prevent/minimise infection

Daily dressing change is not advised. Timing of dressing changes

depends on the product used. Dressing advice can be obtained from your local

Paediatric Burns Unit.

Many burn dressings are available. Dressing choice will depend on

what is stocked at your local service. Below is an example of a safe and

effective initial dressing.

Primary Dressing/Contact Layer

Application of silver dressing as per local methods. A typical

burn dressing may include 7 day Acticoat (alternatives include 3 day Acticoat,

Mepliex Ag, Aquacell Ag).

Secondary Dressing/Fixation

Provides a final layer to absorb exudate and secure primary

dressing/contact layer in place (Melolin, Hyperfix).

Analgesia

Pain management is an important part of paediatric burn care –

uncontrolled stress and pain contribute to poor healing. All procedures should

be performed with adequate sedation and analgesia. Multimodal analgesia is

often necessary to achieve adequate analgesia. Consult local pain service for

advice or opioid infusions/patient controlled analgesia as required for in

patients with severe burns. For minor burns including those managed in the

community consider nitrous oxide or intranasal fentanyl during burn review and

dressing changes. Consider additional analgesia requirements for children who

have had previous distress during dressing changes or ongoing anxiety.

Utilisation of child life therapy, music therapy teams and non-pharmaceutical

distractions (eg iPad, breast feeding, reading, limiting child’s ability to

watch wound care) should complement chemical analgesia and sedation.

Preventing

Infection

Standard infection control measures apply to children with burn

injuries

- Staff and visitors must perform hand

hygiene

- Staff must wear gloves for dressing

changes

- Visitors who are unwell should not

visit the patient

Burns >10% TBSA require additional infection control measures

which aim to limit child’s exposure to bacteria via isolation and limiting

transmission via contact – follow local Paediatric Burns Unit infection

precautions.

Nutrition

Nutrition is an important part of burns care. Children have an

increased metabolic requirement, and increased nutritional requirement for

growth, limited energy reserve and an increased body surface area to mass ratio

compared to adults.

Children who are unable to drink due to facial burns or other

injuries or medical issues should have a nasogastric tube inserted and commence

enteral feeds. A dietician should be involved to ensure adequate nutrition is

met including an assessment of increased macronutrient and micronutrient

requirement (consider supplementation vitamin A, vitamin C and zinc to promote

wound healing). Regular weight measurements aid assessment of adequate

nutrition.

In burns >15% TBSA NGT feeds should be commenced within 6 hours

of the burn.

Positioning

Burn areas should be elevated to limit oedema (monitor for

compromise of peripheral circulation). When a burn crosses a joint, joint

should be positioned to maintain optimal functional range of movement with

consultation with occupational therapy and physiotherapy team.

Post

Acute Care Complications

Itch

Healing wounds are often itchy. Non sedating antihistamines are a

safe option for symptomatic management.

Oedema

Circumferential burns inhibit lymphatic drainage and venous return

resulting in oedema which may take 1-2 weeks to resolve. Elevation of the area

will limit amount of oedema and accelerate resolution of oedema and minimise

neurovascular compromise.

Fever

Fever is a common reaction to hypermetabolic state and immune

response following a burn injury however the child must be assessed for other

causes. Prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended in burns.

If there is concern the burn wound is infected send a swab for MCS

and treat with empiric antibiotics as per local guidelines.

Toxic shock syndrome (TSS) is a rare complication of an infected

burn and can be life threatening.

Signs/symptoms TSS

- Shock (tachycardia, hypotension)

- Fever >38.9 degrees

- Erythematous rash

- Diarrhoea and vomiting

- Lethargy

- Irritability

Treatment includes active resuscitation with IV fluids, IV antibiotics

and urgent paediatric and burns specialty care.

Psychosocial

care

The consequences of a child sustaining a burn can be profound on

the child and their family’s psychological,

emotional, social and financial wellbeing. Children have evolving development

with different physical, cognitive and emotional abilities. Children are

dependent on carers and of children presenting with burn injuries a significant

portion are vulnerable children. Treating a child with a significant burn

injury can involve multiple invasive frightening procedures, protracted

treatments and regular engagement with a health facility. Treatment compliance

is important to achieve the best outcome possible. Caring for the child includes support for

family members which includes multidisciplinary team approach noting a family’s

needs may change from acute care to rehabilitation and the child’s transition

back to community and school.

Rehabilitation

Depending on the size and site burn injuries can be associated

with a significant risk of limited functioning. Appropriate burn care includes

optimising function after a burn to achieve the best possible outcome.

Some burns may require review by occupational therapy or

physiotherapy team, including:

- Hand burns

- Deep dermal or full thickness burns

crossing flexor surface of a joint (risk of contracture)

- Significant oedema limiting limb

function or vascular integrity (poor capillary return, cool to touch distal to

burn)

- Immobilisation by use of splint may be

required to ensure safe position or integrity of underlying body structures

Ongoing OT requirement may be

necessary to optimise patient function and minimise risk of irreversible complication such as contracture and

deformity

Rehabilitation is a long and

intensive process

and will commence as early as possible (often in hospital) and continue at home

with community supports. Therapy may involve a comprehensive plan including

passive and active exercises as well as resting splints. Patients and their family

are required to take on responsibility for and play an active part in ongoing

rehabilitation.

Scar

management

Pressure dressings are utilised to minimise scarring post burn.

Therapists may tailor pressure garments unique to the patient’s requirements and provide exercises to

optimise a patient’s functional outcome.

Skin is altered after a burn and

requires regular moisturising to prevent cracking and breaking down which can

lead to secondary infection.

Burn

reconstruction

Most burns managed well initially will not require reconstruction.

Sometimes burn reconstruction will be recommended to optimise comfort, function

and appearance. This occurs many months

after the initial burn.

Paediatric Home

Safety Tips to Prevent Burns

- Ensure cups of hot liquid are always

out of reach of children

- Thick soup is more viscous and remains on a

child continuing to burn them – wash soup or hot food off with cool running

water and continue first aid for 20 minutes

- Avoid table clothes as children can

pull hot food/drinks down

- Always ensure handles of pots on the

stove are angled in and out of reach of children

- Ensure cords in kitchen not long or

hanging down into child’s reach (eg kettle/toaster able to be pulled down by

loose cord)

- Install a guard around hot plates on

stove

- Ensure deep fryers are OUT of reach of

children

- Block off entry to kitchen with

childproof gate

- Always check bathwater before putting

child in bath

- Put in cold water first, then add hot

water, temperature should not exceed 50 degrees

- Do not leave children unattended in

bath

- can turn on hot tap directly causing

burn

- can electrocute self in bath with

bathroom electronic equipment (hairdryer, shaver etc)

- Always run some cold water through the

tap last so faucet is not hot

- Ensure smoke alarms installed and

functioning to the Australian Standard, replace batteries each year with

daylight savings

- Always supervise children around any

naked flame (candle, fireplace, BBQ)

- Ensure children cannot access

matches/lighters

- Do not use accelerants on an open fire

(eg petrol, grappa, methylated spirits)

- Ensure secure storage of flammable

material within the home

- Do not set off fireworks/flares

- Do not smoke around children, do not

smoke whilst carrying child in baby carrier (ash and cigarette can burn child’s

face)

- Place guards around heaters and teach

children not to touch or stand too close

- Do not leave power cords plugged in

and accessible to children

- Place safety blocks into unused power

points

- Do not use electric blankets in

children’s bed (risk of overheating, risk of electrocution if wet bed)

- Replace any electrical cords that are

frayed/broken down

- Lock up all cleaning materials and

ensure children have no access

- Do not store cleaning materials or

other home maintenance materials

in old food containers (eg coolant in soft drink bottle, snail bait or

rat poison in ice-cream container)

- Ensure batteries are stored away from

access to children

- Limit use of toys/devices requiring

button batteries and if used ensure safety cap over battery compartment are always

securely screwed in

- Ensure running treadmills are

inaccessible to children

- Electricity switched off at power and

unplugged

- In separate room child cannot get into

- Walled off with child’s playpen

[i] W

https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/child/injury/world_report/Burns_english.pdf

[ii] World Health

Organisation, Burns, 2018.

https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/burns

[iii] Australian

Institute of Health and Welfare, Burns and Scalds.

https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/injury/burns-scalds/contents/table-of-contents

[iv] AIHW: Pointer S

& Tovell A 2016. Hospitalised burn injuries, Australia, 2013–14. Injury research

and statistics series no. 102. Cat. no. INJCAT 178. Canberra: AIHW.

[v] Hettiaratchy S, Dziewulski P. ABC of burns: pathophysiology and types of burns British Medical Journal. 2004; 328(7453): 1427–1429.

[iv] Rogers AD, Karpelowsky K, Millar AJW, Argent A, Rode H. Fluid Creep in Major Pediatric Burns European Journal of Pediatric Surgery 2010; 20(2): 133-138.

[vii] CHQ-GDL-06003 – Management of a paediatric burn patient within the Pegg Leditschke Children’s Burns Centre. Children’s Health Queensland Hospital and Health Service.

[viii] Clinical Guideline, Statewide Burn Injury Service – NSW Burns transfer guidelines (4th edition). Page 12 Electrical burns: table Overview of electrical injuries

[ix] Life in the Fast Lane. Carbon Monoxide Inhalation [online]. Dr Neil Long, last update August 25, 2019. Viewed 13th May 2020. https://litfl.com/carbon-monoxide-inhalation/

[x] Life in the Fast Lane. Cyanide Poisoning [online]. Dr Chris Nickson, last update April 2, 2019. Viewed 13th May 2020. https://litfl.com/cyanide-poisoning-ccc/

[xi] Victorian Forensic Paediatric Medicine Service. Burns Including Scald Burns [online]. Viewed 20th April 2020. https://www.rch.org.au/vfpms/guidelines/Burns_including_scald_burns/