Note: This guideline is currently under review.

Introduction

Aim

Definition of terms

Who to contact?

Before, during and after considerations

Evidence Table

References

Introduction

Paediatric patients in hospital may experience many different medical procedures (i.e. having observations conducted, blood taking etc). It is our responsibility as healthcare professionals to ensure that every step is taken to protect children from unnecessary healthcare-induced trauma and

distress, especially those who will be needing ongoing care [1]. The goal of procedural management at RCH is to minimise anxiety associated with these procedures, particularly in light of potential future procedures (See Figure 1). Planning for procedures is essential for ensuring

that the patient’s experience with procedures is a positive one, as poorly managed procedural distress and pain can have long-term negative effects on children and young people [2]. This is best achieved through a multimodal approach incorporating pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches to reduce

distress and improve patient coping with procedures [3].

Aim

The aim of this guideline is to provide guidance as well as adequately prepare clinical staff with the knowledge and effective interventions to support the management of procedure-related distress for children and young people receiving health care.

Definition of terms

Assent: the act of agreeing to or approving of something post thoughtful consideration. This is given by someone who is not of the age to give legal consent

Behaviour Support Profile (BSP): the behavioural support profile is a documentation tool for the non-medical needs of our patients, including their communication preferences/abilities, sensory needs, behaviours of concerns and triggers to name a few. It can be used for any patient with any diagnosis, but is aimed for patients with communication difficulties, behaviours of concern or severe anxiety. For more info click here https://www.rch.org.au/emr-project/learning-resources/Behaviour_Support_Profile/

Consent: to give assent or approval given by someone of legal age or considered a mature minor

Procedural Support: Procedural support is a process of preparing and coaching patients and their families before, during and after medical procedures to promote positive coping skills during any interventions

Procedural Support Plan (PSP): the procedural support plan documents a patient’s preferences for procedures. A general plan can be completed for all procedures, or individual plans for specific procedures can be created. Please refer to the following - Pain / Procedural Support Plan EPIC

Procedural Support Team: A multidisciplinary health professional team working in conjunction with the child’s caregivers form the basis of a procedural support team. The aim of the procedural support team is to promote coping and mastery of medical procedures for the child receiving healthcare.

Who to contact?

| Service |

Child Life

Therapy |

Comfort First |

Comfort Kids |

| Referral criteria |

Referral service:

|

Referral service:

|

Consultative service:

Hospital wide |

| Staff |

Child Life Therapists |

Child Life Therapists |

Clinical Nurse Consultants |

| Contact |

EMR Referral

Intake 52412 |

EMR Referral

52685 (inpatient)

52270 (outpatient)

|

EMR Referral

Phone: 55776/55772

ASCOM: 52771 |

| Hours |

M-F Business hours

ED until 8pm M,T, TH

|

M-F Business hours |

M-F Business hours |

Differences between services

- Child Life Therapists are allied Health

professionals specialising in child development. They provide medical

play, procedure preparation and non-pharmacological procedural

support for children.

- Comfort Kids made up of clinical

nurse consultants who can advise on sedation agents and pharmacotherapy for

procedures as well as provide coordination and planning for procedures and

education to staff

- Comfort First are made up of

allied health professionals who provide procedural preparation and support to

children and adolescents specifically undergoing oncology and Bone Marrow

transplant care.

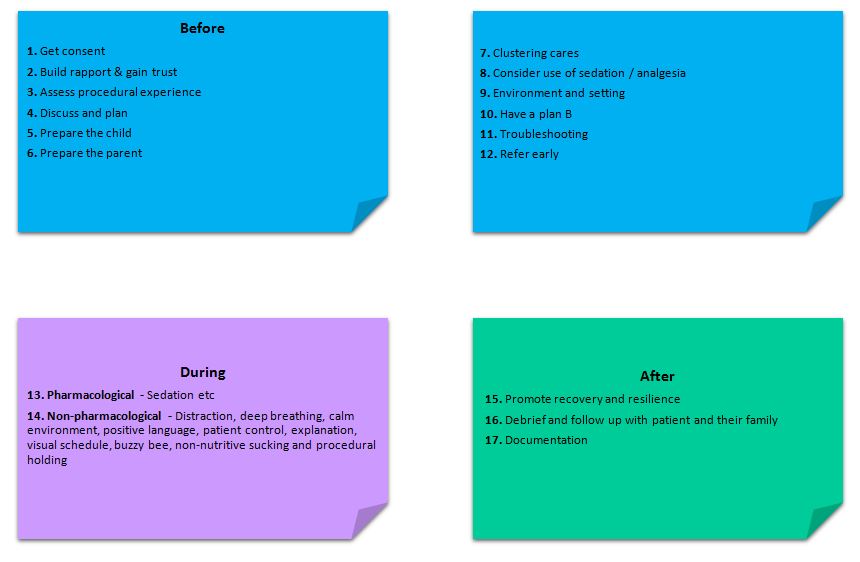

Before, during and after considerations

A guide to conducing a procedure on a paediatric patient.

Before the procedure

1. Consent & assent

- Informed consent should be sought from a parent or

guardian or mature minor for any procedural intervention.

- Verbal consent is adequate for clinical procedures

in the ward environment. Signed consent is required for procedures under

sedation or general anaesthetic.

- A procedure should not go ahead without

parent/guardian consent unless it is in the context of an emergency.

- Where appropriate, assent for the procedure from the

child or young person should be sought in conjunction with parental assent.

- Child assent can be verbal or implied through

co-operation with the procedure.

- Please refer to the RCH Policies and Procedure: Consent - Informed

- Consent requirements are more complex for medical

imaging procedures. Please refer to the document attached:

2. Building a rapport & gaining

trust

- It takes a small

amount of time to ask the child about their likes and dislikes (pets, siblings,

favourite toy, favourite TV show)

- Demonstrating you know

something important to the child facilitates trust

3. Assess procedural experience

- Discuss with the patient/family their previous experience

of procedures (if any)

- What worked well? What didn't work well? How did the child

respond when informed about the procedure? Which part of the procedure might bother the

child most?

- Does the child have

any coping strategies that they already use

4. Discuss and plan

- Offer

choices, where possible, of how the procedure can be completed

- Have

a staff discussion prior to the procedure, assign roles and consider ‘Plan

B’ options

- Consider the use of Buzzy Bee, ice packs

or Coolsense.

- Consider

the use and allow adequate time for topical anaesthetic (AnGEL & Emla) as

tolerated. LINK COMING SOON.

- Be

ready to tailor your practice to the specific needs of the child as your preferred

way of practice may need to be adjusted to suit the child.

- Complete

or update the Pain/Procedural Support Plan in EMR

5. Prepare the child

- Children vary in the

amount of information they want to know about a procedure. Discuss with the

parent to assess the best way to communicate the procedure to the child.

- The timing of when you

explain the procedure to a child will depend on the child’s age, development

and their degree of anxiety, generally:

- Younger (≤ 7 years)

and more anxious children can be told on the day of the medical procedure. Toddlers

and Preschool aged children may be best prepared for the procedure just prior

to the intervention.

- Older ( ≥ 8 years) children can be told the day before or

within the week of the medical procedure [4]

- Use soft language

and avoid the use of medical words that can be confusing to children (refer to

this guideline for more info RCH Clinical Practice Guideline: Communicating procedures to children

- Assess

the child’s methods and preferences for communication

- Children

from CALD backgrounds should be assessed for the need for an interpreter, and

if required should be booked. See booking information here https://www.rch.org.au/interpreter/booking_an_interpreter/

- Children

who are non-verbal (or who prefer it) should be offered a visual schedule or

the procedure should be explained through their preferred communication method.

Contact CLT, speech pathology, Comfort Kids or Comfort First to facilitate this

- If called in advance,

Child Life Therapists can provide preparation for specific procedures (eg.

Modelling an IV insertion on a calico doll, familiarising the child with the

“straw” that goes in their arm)

- The RCH has created a

number of resources to help prepare children for medical procedures:

6. Prepare the parent

- A family member should be encouraged to stay

during the procedure to support the child as this can reduce distress [5], but

always check parent’s preference.

- Give the parent a clear role, don’t assume the

parent knows what to do during the procedure. In most cases this will be to

comfort the child, but make sure you explain what they should do in the

procedure [6]

- Provide parents with procedural information so

they know what to expect as this can reduce parental anxiety and enhance the

success of the medical procedure [5,6]

7. Clustering cares/procedures

- Consider if multiple

procedures can be done at the same time (eg. Plan to insert an NGT under

sedation, can tomorrow’s bloods be brought forward to be completed during the

same sedation episode?)

- Is there an upcoming surgery

scheduled? Consider clustering procedures together when the child is

anaesthetised

- However, a sedation event shouldn’t be relied on to

fit every intervention into one sitting, as using nonpharmacological methods

for low impact procedures on different occasions can be done effectively

8. Consider use of sedation/analgesia

- If the medical

procedure is likely to cause discomfort, consider the use of analgesia if appropriate

[7].

- Consider procedural

sedation if (1) the child has a history of significant procedural distress (2) the child is required to be immobile for

a long period of time [8]

- Medication and dosages

can be found here RCH Policies and Procedure: Procedural Sedation - Ward and Ambulatory Areas

9. Environment & setting

- There is evidence to support that modifying the

environment a procedure occurs in can positively impact on the child’s

perception of pain [7, 9].

- Where

possible dim lights and minimize unnecessary equipment in room [8]

- One voice: The person distracting or coaching the patient through the

intervention should be the one voice heard through the procedure [10].

- The treatment room is recommended for procedures

to help maintain the patient’s bed and room as a safe space [11]. This may be

especially true for infants and toddlers who might otherwise begin to perceive

a threat every time a staff member enters their room. However, the environment

in which the procedure takes place should be negotiated with the patient and

their family, therefore giving the patient a sense of control.

- Equipment and staff should be prepared before

the child enters the procedural setting and it is recommended that any

equipment that may provoke fear be kept out of sight.

- Reduce the number of unnecessary people who

are not involved in the procedure to help minimise anticipatory anxiety

10. When to abort the procedure – Having a “Plan

B”

- It is important to

discuss with the parent and those involved in the procedure in advance what

will happen if the procedure fails and when to stop

- Setting clear

boundaries for when to abort a procedure in advance makes it easier to stop

when things aren’t going to plan

- Discussing a “Plan B”

in advance puts less pressure on Plan A being forced if the procedure isn’t

working

11. Trouble shooting when you have no

time - Consider:

- How important and time

sensitive the procedure is?

- Can it wait? If so,

challenge those wanting to proceed (even parents) without a plan

- If there is no time to

plan and prepare, what is the likelihood of a successful outcome?

12. Refer early to Comfort Kids/First and

Child life therapy if the child has a history of:

- Previous high procedural distress

- Trauma

- Developmental delay or intellectual disability or sensory

processing syndromes

- Any special needs that you consider may impact on the child’s

ability to cope with a medical procedure

Automatic

referrals to Child Life Therapy, Comfort Kids and Comfort First can be

generated through Nursing Admission navigator on EMR in the wellbeing screening

section. Please refer to the following - https://www.rch.org.au/emr-project/learning-resources/Nursing_Admission/

Patients

with additional needs

- Including those with neurodevelopmental disorders

and developmental disabilities

- These

patients may need or already have an individualised support plan such as a PSP

& BSP that take into account their

specific needs/requirements

13. Pharmacological strategies

Sedation

should not be viewed as a last resort and the patient should not be seen to

have failed because they need sedation. However, sedation is not an alternative

to non-pharmacological techniques. They are used in conjunction. Sedation

should be considered if [10]:

- The child

displays significant anticipatory anxiety +/- fear related to the

procedure

- The medical

procedure is considered to cause discomfort beyond the child’s ability to cope

- The procedure is

expected to be lengthy and / or the child is expected to be immobile for a long

period of time

Refer to the procedure on procedural

sedation in ambulatory areas for further information RCH Policies and Procedure: Procedural Sedation - Ward and Ambulatory Areas

During

the procedure

14. Non-pharmacological and psychological

strategies

Distraction

Distraction can provide

patients with a positive alternative focus which can help to reduce perceptions

of pain during an intervention [12]. Distraction should be engaging,

interactive and suit the developmental level of the patient. Distraction is

best done by one person in the room to help create a calm environment.

Suggestions:

- Bubbles

- Singing or listening to a favourite song

- Exploring novelty toys

- Books with noisy buttons or find it books.

- Using technology such as phones, tablets or TV can be a motivating

distraction for patients. They may

prefer familiar shows, songs or apps.

- Non-procedural talk and humour

Notes:

- Some

patients may want to watch the procedure, if that is their preference that is

ok.

- Distraction

is not meant to trick a patient. It is a tool to help patients cope with medical

procedures or interventions.

Deep

breathing

Deep

breathing techniques can be used as a coping strategy to help a patient

regulate their anxiety and perceptions of pain during an intervention [12, 13].

Increasing

the supply of oxygen to the brain can reduce the sympathetic nervous system

response (fight or flight) and help to calm anxiety by activating the

parasympathetic nervous system (relaxation and calm) [14].

Suggestions:

- For younger patients blowing bubbles, blowing a pinwheel or

leaning on a parent who is taking slow deep breaths can help prompt deep

breathing

- Giving suggestions such as smelling a flower or pretending to blow

out birthday candles can help prompt deep breathing

- Getting the patient to place a hand over their tummy and practice

4x4 breathing (inhaling deeply to the count of 4 and exhaling slowly to the

count of 4).

Notes:

These techniques will be more effective if the patient has had time to

briefly practice these ideas before the intervention

Guided imagery

Guided

imagery can be used and taught to patients to help them deal with a painful or

anxiety provoking situation [15]. Guided imagery involves drawing a picture of

a place in the patient’s mind that relaxes them. Guided imagery may be

elaborate or a simple visualisation.

Suggestions:

- Storytelling

- Meditation

- Progressive muscle relaxation

Note:

These techniques will be more

effective if the patient has had time to practice these ideas before the intervention.

Maintaining a calm environment

Procedures and the medical

environments in which they occur can be frightening for paediatric patients. A

quiet and low stimulus room will reduce the potential for the patient to become

overwhelmed.

Suggestions:

- One voice: The person

distracting or coaching the patient through the intervention should be the one

voice heard through the procedure.

Note:

The treatment room is recommended for

procedures to help maintain the patient’s bed and room as a safe space. This is

especially true for infants and toddlers who might otherwise begin to perceive

a threat every time a staff member enters their room.

Communicating during a procedure

Positive

language

The use of

age-appropriate and positive language when supporting patients is integral in

aiding coping and cooperation. Communication that creates negative expectations

of the procedure will increase reported levels of pain [16].

Suggestions:

- Focus on the positive and use neutral developmentally appropriate language

where possible. For example - saying

“this may sting/ burn” prior to an IV insertion increases anticipatory

anxiety and suggests pain (nocebo effect) [17]. Instead saying “Here comes a push. Let us know how it feels

for you” allows the patient to have their own experience.

- Be honest but use language that is developmentally appropriate. For example – Instead of “It’s time for your needle” try “It’s time to get your body ready to have your

medicine”.

- Avoid complex or unfamiliar medical terminology as patients may

have difficulty interpreting unfamiliar medical words which may cause anxiety

and cause worry. For example- Instead of “you need to have a CT to get an accurate diagnosis” you could say “we

need to take some pictures to help us see how your body is going”.

- It’s important to acknowledge and

validate the patient’s feelings (I can

see this feels a bit tricky for you) rather than diminish (that doesn’t hurt, it’s not scary’).

- It’s ok for a patient to cry. This may be

how the patient copes

or may be a developmentally appropriate response. Consider stopping the

procedure and consulting with the procedural team if this response appears

beyond a normal coping response

Promoting

patient control

Assigning the patient a role can help a patient feel in control

and helps them build a sense of mastery. Give the patient-controlled

choices to help engage them as active participants in their medical treatment

[18]. For example:

- Instead of telling a patient what they need to do (‘be still’), assign them a role “your special job is to keep your arm as still as a statue”.

- Let them choose: Would you like to watch or look away?

- Create choice wherever there is opportunity to: Would you like to sit up in the chair by yourself or on mum’s lap? or Which arm would you like me to take your blood pressure on?

- Offering the patient a way to request a pause or a break in the procedure may help a patient regroup if they are starting to become distressed. “I think you might need a little break? Let’s count to 10 together (or set a timer on phone).”

- Identifying things that the patient has done well even if they have found the procedure difficult can help the patient reframe the experience and give them a takeaway to focus on next time. An example of this might be “I could see you tried hard to be still. Well done!”

Step by step explanation

Some patients may want a very simple step by step explanation about what is happening during the procedure. Asking a patient if they want to know what is happening or if they prefer to look at something else can help to give the patient control of how they might want to be involved in the procedure.

Visual schedules

Visual schedules are a set of pictures which show the steps of an activity or intervention. They can help break an intervention down into smaller achievable stages that the patient can see themselves progressing through, which may otherwise seem overwhelming and difficult to begin [19]. Visual schedules are frequently used with patients with autism spectrum disorder and developmental disabilities, but they may also be useful with many other children or CALD patients.

|  |

Suggestions:

Visual schedules could be used for many different interventions including nursing observations or IV access.

Note:

RCH Child Life Therapy have a license to use Boardmaker software to create visual schedules for common procedures

Use of the Buzzy and ice

Buzzy is a vibration device that can help to dull or eliminate the pain by confusing the body’s nerves and distracting away from a painful stimulus [20]. Buzzy is recommended to be used in combination with an ice pack if the patient can tolerate the cold sensation (Buzzy® Device PowerPoint Presentation).

Note:

Buzzy is best introduced to the patient prior to the intervention to see if the patient will tolerate the strong vibration sensation.

Ice packs may also be used without Buzzy if a child prefers for interventions such as immunisations or injections if the patient has found this to be helpful.

Breastfeeding, sucrose and EBM for procedural pain management

Breastfeeding is preferable when available as parent contact, especially skin to skin provides comfort. Sucrose is safe and effective at reducing pain during procedures, such as heal lance. Although most effective in neonates less than 28 days, the RCH recommends use for infants up to 18 months. Sucrose is most effective when used in combination of supportive measures, such as swaddling and containment (refer to sucrose guideline). Although EBM is not as effective at reducing pain when compared to sucrose or breastfeeding, it can be considered as an alternative intervention.

Procedural holding

Procedural holding or ‘Positioning for comfort’ promotes the use of upright positioning and close contact to the parent/guardian. Positioning for comfort facilitates safe access to the part of the body required for the medical procedure without removing the child’s right to freedom of movement.

Swaddling and facilitated tucking for young infants (0-3 months) may provide comfort [21]. For infants older than 3 months more upright positioning and close contact with parent/carer is recommended.

Sitting upright during a procedure has been demonstrated to reduce fear and distress during medical procedures [3] and enhances the patient’s sense of control over the medical procedure. The patient can engage in distraction, monitor the progress of the procedure or look away.

Suggestions:

- Encouraging parents to include positive touch during a procedural hold may help build comfort for the patient, this may include stroking, hugging, massage

Notes:

When to stop a procedure (Refer to “Plan B” in before section)

- Stop the procedure if the intervention is not urgent and you feel the patient is unable to cooperate and/ or appears too distressed.

- Consult with parents or caregivers and discuss other options to help the child settle and potentially proceed.

After the procedure

15. Promote recovery and resilience

Children’s memories of painful experiences are strong

predictors of subsequent reports of pain intensity [24]. Therefore, it is

integral that any medical procedure

is ended in a positive manner for the patient by:

- Reducing

the child’s distress before leaving the procedural setting can help to reduce

negative associations with treatment spaces. Offer the patient an opportunity

for cuddles with the caregiver, provide positive reinforcement of what went

well during the procedure and asking them to make choices about what they are

doing next may help to promote recovery.

- ‘Bookending’

(positive experiences before and after) a procedure can help to reduce negative

associations with medical interventions.

16. Debrief and follow up with patient and their family

- Get feedback - Find out what worked well and what didn’t

- Ask if there is anything the child would like to try differently

next time

17. Documentation

- Document

the child’s response to the medical procedure and procedural preferences to

help inform subsequent interventions

- Even if it didn’t go to plan so it

can be planned better next time

- Patients should have their procedural support

plans updated regularly to reflect changes in coping

- Include the following when documenting the procedure:

- How the procedure went?

- Was it successful? How many attempts were made?

- Positioning / restraint used

- Who was present in the room and their roles

- Where was the procedure conducted?

- Forms of non – pharmacological strategies used

- Detail any specific parent or patient requests

- Utilise Sedation narrator if warranted or appropriate

- Consider using smart phrases

to document this to ensure that all relevant information is included for

future procedures

Evidence Table

The evidence table for this procedure management nursing guideline can be accessed here.

References

- Lewrick, J.L. (2016). Minimizing

pediatric healthcare-induced anxiety and trauma. World Journal of Clinical

Pediatrics, 5(2); 143-150.

- Young, K., Pediatric Procedural Pain.

Annals of Emergency Medicine, 2005. 45(2): p. 160-171.

- Taddio, A., et al., (2015). Reducing

pain during vaccine injections: clinical practice guideline. Canadian Medical

Association Journal.

- Twycross, A., S. Dowden, and E.

Bruce, Managing pain in children: a clinical guide. 2009, Wiley-Blackwell:

United Kingdom.

- Loeffen, et al. (2020). Reducing pain

and distress related to needle procedures in children with cancer: A clinical

practice guideline. European Journal of Cancer, 131, 53–67.

- Srouji, R., S. Ratnapalan, and S.

Schneeweiss, Pain in Children: Assessment and Nonpharmacological Management.

International Journal of Pediatrics, 2010. 2010: p. 11.

- Young, K., Pediatric Procedural Pain.

Annals of Emergency Medicine, 2005. 45(2): p. 160-171.

- Krauss B, & Green SM. (2000).

Primary care. Sedation and analgesia for procedures in children. New England

Journal of Medicine, 342(13), 938–945.

- Pillai Riddell, R., et al.,

Nonpharmacological management of procedural pain in infants and young children:

an abridged Cochrane review. Pain Res Manag, 2011. 16(5): p. 321-30.

- Boles, J. (2013). "Speaking up

for children undergoing procedures: the ONE VOICE approach." Pediatric

Nursing 39(5): 257-259).

- Fanurik, Debra & Schmitz, Michael

& Reach, Kelle & Haynes, Katherine & Leatherman, Isabel. (2000).

Hospital Room or Treatment Room for Pediatric Inpatient Procedures: Which

Location Do Parents and Children Prefer?. Pain Research and Management. 5.

148-156.

- Birnie KA, Noel

M, Chambers CT, Uman LS, Parker

JA. Psychological interventions for needle‐related procedural pain and

distress in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

2018, Issue 10.

- Bagheriyan, S., Borhani, F.,

Abbaszadeh, A., & Ranjbar, H. (2011). The effects of regular breathing

exercise and making bubbles on the pain of catheter insertion in school age

children. Iranian journal of nursing and midwifery research, 16(2), 174–180.

- Brown, Richard & Gerbarg,

Patricia & Muench, Fred. (2013). Breathing Practices for Treatment of

Psychiatric and Stress-Related Medical Conditions. The Psychiatric clinics of

North America. 36. 121-40.

- Vagnoli, A Bettini, E Amore, S De

Masi, A Messeri, (2019). Relaxation-guided imagery reduces perioperative anxiety

and pain in children: a randomized study. European journal of pediatrics, 2019, 178(6), 913‐921).

- Fusco N, Bernard F, Roelants F,

Watremez C, Musellec H, Laviolle B, Beloeil H, (2020). Hypnosis and

communication reduce pain and anxiety in peripheral intravenous cannulation:

effect of Language and Confusion on Pain During Peripheral Intravenous

Catheterization (KTHYPE), a multicentre randomised trial. British journal of

anaesthesia, 2020, 124(3), 292

- M, Sometti D, Tinazzi M & Fiorio

M. (2019). When words hurt: Verbal suggestion prevails over conditioning in

inducing the motor nocebo effect. European Journal of Neuroscience, 50,

3311-3326.).

- Harrison, C. 2004. Treatment

decisions regarding infants, children and adolescents. Paediatrics & child

health, 9(2), 99–114.

- Mesibov GB, Browder DM, Kirkland C.

Using Individualized Schedules as a Component of Positive Behavioral Support

for Students with Developmental Disabilities. Journal of Positive Behavior

Interventions. 2002;4(2):73-79).

- Taddio, A. B. M. P., et al. (2015).

"Procedural and Physical Interventions for Vaccine Injections: Systematic

Review of Randomized Controlled Trials and Quasi-Randomized Controlled

Trials." Clinical Journal of Pain 31 Supplement (10S): S20-S37).

- Pillai Riddell RR, Racine NM,

Turcotte K, et al. 2015. Non-pharmacological management of infant and young

child procedural pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2015 (10).

- McGrath et al (2002).Holding the

child down" for treatment in paediatric haematology: the ethical, legal

and practice implications. Journal of law and medicine 10(1):84-96.

- Snyder BS. 2004. Preventing

treatment interference: Nurses’ and parents’ intervention strategies.

Pediatric Nursing 30: 31–40.

- Noel, M., et al., The

influence of children's pain memories on subsequent pain experience. Pain,

2012. 153(8): p. 1563-1572.

Please remember to read the disclaimer.

The development of this nursing guideline was coordinated by Charmaine Cini, CSN, Koala Wards, and approved by the Nursing Clinical Effectiveness Committee. Updated December 2020.