See also

This CPG discusses diagnosis and management of cerebral palsy (CP) in the outpatient setting. For acute management, refer to:

Key points

- CP is a non-progressive motor disorder with many different causes. Children with CP require investigation to determine the underlying cause and exclude progressive conditions

- Infants with (or at high risk of) CP benefit from early intervention to optimise functional outcomes and to screen for and manage comorbidities

- Care of children with CP requires a multidisciplinary team, and should be tailored to the goals of the child and family

- Whilst the underlying cause is non-progressive, clinical features may evolve. Monitor with regular reviews for complications

Background

- CP is an umbrella term encompassing a heterogenous group of permanent disorders of movement and posture resulting from non-progressive damage to the developing infant or fetal brain

- 75% of cases are secondary to events in the antenatal period, 15% perinatal and 10% postnatal

- Diagnosis is made clinically, typically before 12-24 months of age, though early diagnosis may be made as early as 3 months corrected gestational age (CGA). Some children are identified as being at high risk for CP, and this supports their access to early intervention and supports

- Although CP is non-progressive, the clinical picture changes over time

- May be accompanied by difficulties in cognition (30-60%), communication, hearing, vision, behaviour, sleep, feeding and sensation, mental health and pain

- Children with CP are at an increased risk of secondary medical issues such as epilepsy, musculoskeletal problems and recurrent infections and often encounter impairment in development and function which can significantly impact their participation in daily life. With the right resources, treatment, and support, people with CP can thrive and live fulfilling lives

Assessment

The goal of assessment is to identify at-risk infants, establish a clinical CP diagnosis, identify the underlying cause, identify the degree of impairment and monitor for motor and non-motor complications

Key features of diagnosis include:

- Presence of risk factors for CP

- Motor impairment attributable to insult to the developing fetal or infant brain, resulting in functional limitations

- Evidence of permanent and non-progressive brain injury

History

- Screen for risk factors, including:

- Family history: CP, stillbirths, miscarriages, intellectual disability, seizures, movement disorders

- Prenatal: maternal infection during pregnancy, pregnancy complications, multiple pregnancy

- Perinatal: acute hypoxic event, prematurity, low birth weight, neonatal infection, neonatal seizures, special care/NICU admission, postnatal steroids prior to 32 weeks CGA, mechanical ventilation

- Postnatal: stroke, brain injury, CNS infection

- Features suggestive of motor impairment, warranting referral (use corrected age):

- Persistent fisting of the hands beyond 4 months

- Persistent head lag beyond 4 months

- Unable to sit without support beyond 9 months of age

- Stiffness or tightness in the legs between 6--12 months (eg unable to bring toes to mouth during nappy change)

- Handedness before 12 months

- Not walking by 18 months of age

- Consider referral if

- Persistent startle (Moro) reflex beyond 6 months of age

- Consistent asymmetric or toe-walking beyond 12 months of age

- Persistence of primitive reflexes

- Features suggestive of an alternate diagnosis (ie metabolic, neurodegenerative, etc)

- Loss of previously acquired skills or progressive symptoms

- Dysmorphic features

- Marked worsening during fasting periods or illness

- Muscle atrophy

- Sensory loss

- Family history of alternative genetic condition

Examination

- Growth parameters

- Dysmorphic features

- Neurological: gait, tone, posture, power, coordination, reflexes, motor milestones, hand preference, hearing and vision, bulbar function

- Musculoskeletal: scoliosis, hip dislocation, contractions

- Respiratory: excessive drooling, signs of aspiration lung disease

Motor assessments

Identifying motor impairment generally involves the use of assessments by a trained professional eg Prechtl General Movements Assessment (GMA), Hammersmith Infant Neurological Exam (HINE)

Classification

CP is typically classified based on the pattern of motor impairment, topography and the degree of functional impairment

- Motor phenotype: spastic, dyskinetic (dystonic and choreoathetotic), ataxic. Mixed movement disorder (ie both spasticity and dystonia) is common

- Topography: unilateral, bilateral OR diplegic, hemiplegic, quadriplegic

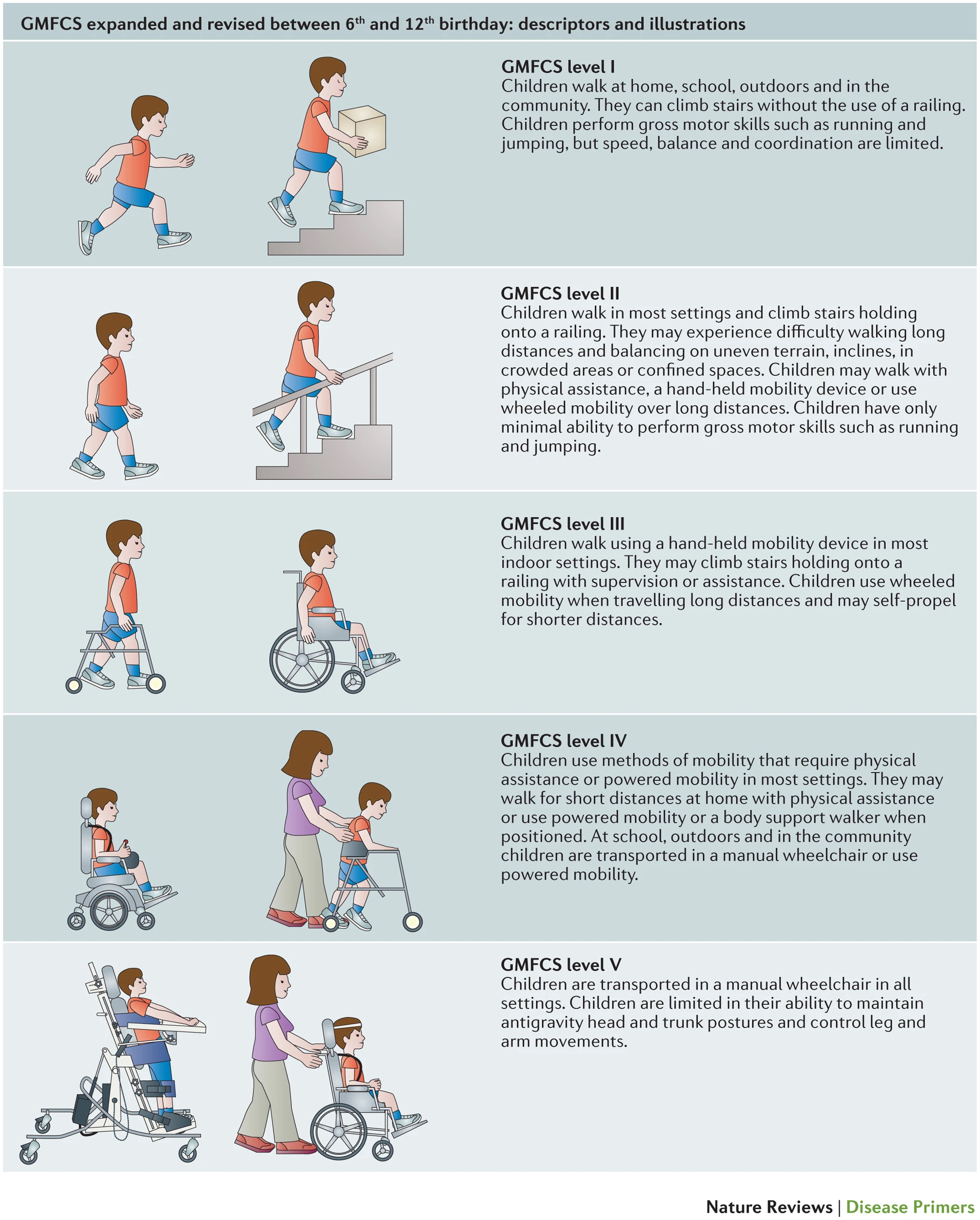

- Functional motor impairment: using scores such as the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS)

GMFCS Classification for children with CP 6-12 years of age

Management

Investigations

Although CP is a clinical diagnosis, all children should undergo investigations to identify the underlying cause and exclude progressive conditions

Neuroimaging

- Cranial ultrasound

- In neonatal period, may result in earlier detection of lesions that increase risk of CP

- May miss subtle or peripheral lesions

- MRI brain

- At term equivalent if severe impairment or progressive symptoms, though subtle lesions may be difficult to detect at this age

- Consider after 2 years of age (when cerebral myelination complete) if initial MRI normal/inconclusive or not done at term equivalent

- Approx 10-15% of children with clinically diagnosed CP have a normal MRI at 2 years of age

Genetic testing

- Microarray is generally first line

- Consider whole exome sequence (ideally trio) +/- genetics referral if microarray normal (25% or more may have a genetic cause and this can coexist with other risk factors)

Other investigations

Consider other investigations in consultation with relevant specialist when assessment is suggestive of underlying infectious, metabolic or genetic causes or when neuroimaging is suggestive of a specific cause or is non-diagnostic

This may include:

- Investigation for perinatal infection (see ASID guidelines)

- Metabolic tests eg blood gas, creatine kinase, ammonia, urine metabolic screen

- Thrombophilia screen if hemiplegia or evidence of cerebral infarct on imaging or family history

Treatment

Assessment and management by a multidisciplinary team is essential

- Physiotherapists give practical advice on positioning and handling to minimise the effects of abnormal muscle tone and encourage the development of movement skills. They also advise about the use of orthoses (eg ankle foot orthoses), wheelchairs and other mobility aids and assist in gait rehabilitation and improve opportunities for meaningful participation and access

- Occupational therapists help parents to develop their child's upper limb skills, age-appropriate independence over time, recommend suitable toys, equipment and home adaptations and can support management of sensory issues

- Speech pathologists assist in the development of communication skills and advise about augmentative communication systems. They provide guidance with feeding difficulties and saliva control problems

- Other team members may include dietitians, orthotists, social workers, psychologists, special education teachers and nurses

Motor problems

Spasticity

- In focal/segmental spasticity, consider injected botulinum toxin

- Generalised spasticity

- Oral medications such as baclofen are first line

- Other interventions such as intrathecal baclofen pump (ITB) or selective dorsal rhizotomy may be considered in rare cases by rehab services

Dystonia

- Whilst evidence for dystonia management is lacking, some specialists may consider below options

- In focal/segmental dystonia, consider injected botulinum toxin

- Generalised dystonia

- Oral baclofen is generally first line

- Oral/transdermal clonidine or oral gabapentin can be added if baclofen is insufficient

- In some children, CP specialists may consider other medications (eg benzodiazepines, levodopa, trihexyphenidyl) or in severe generalised dystonia, ITB or deep brain stimulation

Musculoskeletal problems

- Muscle contractures and torsion of long bones

- Progressive contractures typically develop as long bones grow

- Early hypertonia management (see below), casting, splinting night braces, etc

- Orthopaedic surgery (rarely required prior to 6 years old)

- Hip displacement and scoliosis (see AACPDM guidelines)

- All children with CP should undergo hip surveillance to monitor for early signs of hip displacement

- Increasing motor impairment correlates with increasing risk of hip dislocation and scoliosis

- Initial clinical assessment (pain, change in function, examination of hip and spine) at 12 months of age +/- AP hip radiograph (not required in GMFCS I)

- Frequency depends on identified issues and degree of motor impairment

- Concerns identified on surveillance prompt orthopaedic referral, for consideration of preventative and reconstructive surgery

- Knee surveillance

- Monitor for knee flexion deformity in those with GMFSC I-III from 5 years until skeletal maturity

- Can cause functional impairment, crouched gait, pain, and loss of walking ability

Impaired saliva control (see Saliva Control in Children handbook)

- May be anterior (may cause skin breakdown, social challenges) or posterior (causing choking and aspiration)

- Motivated children benefit from speech therapy or behavioural interventions for anterior drooling. Other strategies include positioning, suctioning, assessing for gastrooesophageal reflux (see below)

- Consider anticholinergic agents

- Botulinum toxin injections of salivary glands and/or surgical management may be considered in some children

Constipation

- Common due to gut dysmotility, diet, fluid intake, non-ambulant status and medication side effects

- May impact bladder function, absorption of medications and cause discomfort

- See Constipation

Urinary incontinence

- Resulting from cognitive, communicative or physical impairments, constipation and/or detrusor over-activity

- Toilet training may take longer in children with CP however many achieve bladder control

- May require medical management, and/or clean intermittent catheterisation if neurogenic bladder. Consider urology referral

Associated health problems

CP can be accompanied by a range of other health problems, which should be screened for at regular visits

Associated health problems in CP and recommended monitoring and interventions

| Associated health problem |

Description |

Intervention |

| Growth and feeding problems |

Common due to oromotor dysfunction and gut dysmotility |

Monitor growth and micronutrients and provide dietary advice

Consider enteral tube feeding for weight gain, to reduce nutritional deficiencies, provide a route for medication administration and reduce aspiration risk

See Micronutrient deficiency for management of specific deficiencies |

| Respiratory disorders |

Increased risk of aspiration, restrictive lung disease due to chest wall deformity and/or scoliosis, recurrent chest infections, central and/or obstructive sleep apnoea |

See Cerebral palsy -- chest infection

Immunisation, including yearly influenza vaccines |

| Hearing loss |

In approx 10%

Increased risk of both conductive (due to recurrent OM) and sensorineural hearing loss |

Regular audiology assessments guided by clinical features |

| Vision loss |

In 30-50% |

Regular ophthalmological assessments |

| Intellectual disability |

In up to 45% |

Most children benefit from formal cognitive assessment (appropriate for their motor or communication impairments) and educational support ideally in the year prior to commencing school |

| Communication disability |

Can occur in context of normal intellect, or with co-occurring intellectual disability |

Educational support and speech pathology - consider augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) strategies |

| Epilepsy |

In up to 50% |

See Cerebral palsy -- increased seizures |

| Gastrointestinal disorders |

Increased risk of gastroesophageal reflux, constipation or gut dysmotility/delayed gastric emptying or gastrointestinal dystonia |

Monitor for symptoms |

| Low bone mineral density |

Increased risk due to nutrition, non-weight bearing status, and/or medication effects (eg anti-seizure medication)

Increased risk of pathological fractures |

Check Vitamin D yearly

Optimise calcium intake, exercise (swimming, recumbent bikes etc) and environmental sunlight exposure |

| Other associations |

Poor dentition

Sleep disorders

Mental health and behavioural problems

Challenges in menstrual management

Delayed puberty |

|

Consider consultation with local paediatric team when

- Infant with risk factors or clinical features of CP

- Child requiring admission

Consider transfer when

The care required for the child is beyond the comfort level of the health care service

For emergency advice and paediatric or neonatal ICU transfers, see Retrieval Services

Consider discharge when

Appropriate follow up has been arranged

Parent information

Raising Children Network -- Cerebral palsy

SCHN Factsheet -- Cerebral palsy

Kids Health Info -- Cerebral palsy

Saliva Control in Children

Additional notes

AACPDM Hip surveillance guidelines

AACPDM Care Pathways

Starship Cerebral Palsy Clinical Network

Cerebral palsy for general practitioners factsheets

Last updated November 2025

Reference list

- AACPDM. Cerebral palsy and dystonia: Care Pathway. Retrieved from: https://www.aacpdm.org/publications/care-pathways/dystonia-in-cerebral-palsy (August 2025)

- Barclay, A, et al. Definition, investigation and management of gastrointestinal dystonia in children and young people with neurodisability. Archives of disease in childhood. 2025;110(9), 742--750

- Barkoudah, E, Aravamuthan, B. Cerebral Palsy: Classification and clinical features. Uptodate June 2024. Retrieved from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/cerebral-palsy-classification-and-clinical-features (May 2025)

- Barkoudah, E, Aravamuthan, B. Cerebral Palsy: Evaluation and diagnosis. Uptodate May 2025. Retrieved from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/cerebral-palsy-evaluation-and-diagnosis (May 2025)

- Boychuck Z, et al; Prompt Group. International expert recommendations of clinical features to prompt referral for diagnostic assessment of cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2020;62(1):89-96

- Einspieler C, Prechtl HF. Prechtl's assessment of general movements: a diagnostic tool for the functional assessment of the young nervous system. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2005;11(1):61-7

- Fehlings D, et al. Pharmacological and neurosurgical management of cerebral palsy and dystonia: Clinical practice guideline update. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2024 Sep;66(9):1133-1147

- Graham H, et al. Cerebral palsy. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016 Jan 7;2:15082

- Lewis SA, Chopra M, Cohen JS, et al. Clinical Actionability of Genetic Findings in Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2025;179(2)

- Reddihough D, et al. Cerebral palsy for general practitioners. MCRI Collection. 2018

- Reid S, e al. Intellectual disability in cerebral palsy: a population-based retrospective study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018;60(7):687

- Reid, S, et al. (2011, September 6). A Population-Based Study and Systematic Review of Hearing Loss in Children with Cerebral Palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 53(11), 1038-45

- Rhodes, L et al. Assessment and management of low bone mineral density in children with cerebral palsy, Journal of the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America, 2024;7, 2768-2765

- Rosenbaum P, et al. A report: the definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev Med Chil Neurol 2007; 109(Suppl): 8--14

- Thomason P, et al. Knee surveillance for ambulant children with cerebral palsy. J Child Orthop. 2025;19(4):253-266