See also

Death of a child: Resources

Key points

- The death of a child is distressing for the family and carers, and can be confronting for healthcare providers

- The care provided should be respectful and inclusive of any cultural, religious, spiritual and family beliefs. Involvement of appropriate representatives should be encouraged

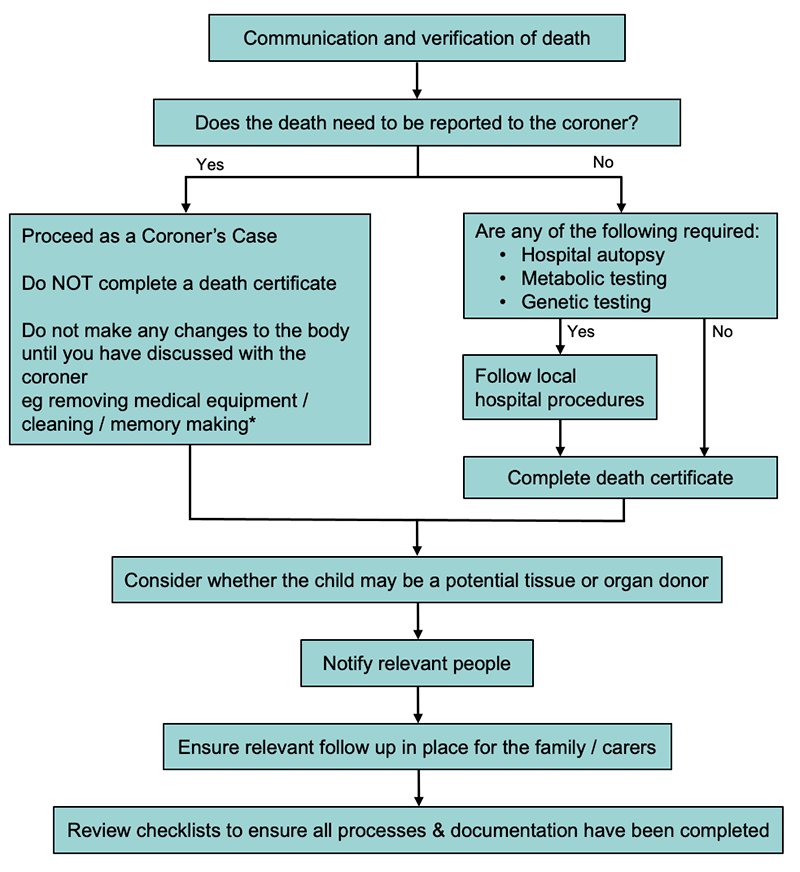

- Always consider whether a death should be reported to the coroner, and seek advice if this is unclear

- Always consider the possibility of organ or tissue donation, and contact your hospital representative or the team at Donate Life for guidance

- Aim to complete all relevant forms as soon as practicable, and ensure family have any required documentation and follow up arranged prior to leaving the hospital

Background

The aim of this guideline is to provide stepwise guidance on the key procedures and processes relating to the death of a child

- There are variations in practice between states and hospitals, this guideline should be used in conjunction with

local resources

- While there are key procedures that need to be followed, it is imperative that the child, family and carers’ needs and requests are respected and considered

- A multidisciplinary approach is invaluable and may include an extended group of healthcare providers and other specialist teams

Spiritual, Religious and Cultural Considerations

- It is important to recognise the significance of cultural, religious, spiritual and family beliefs in the setting of death and bereavement, and the impact of these in the ongoing welfare and support of the family and carers

- Ask the family or carers if they have any specific requests or if there is anything that is particularly important to them during this time

- Where appropriate, engage pastoral, spiritual and cultural representatives, such as the aboriginal liaison team, along with the social work team to offer guidance and support

Other Special Considerations

- For sudden unexplained death in infancy (SUDI) see

Death of a child: Sudden unexplained death in infancy

- For children with an infectious disease that has specific precautions, such as the use of personal protective equipment, explain the necessary precautions to the family and ensure that these are followed, see

local policies

- If the child has recently been treated with radioactive materials, safe handling is required, see

local policies

- Infection or presence of radiopharmaceuticals in the child’s body may affect body repatriation and restrict tissue or organ donation, see

local policies

Medical procedures

*Consider offering memory making opportunities eg hand or foot prints, lock of hair, photos, memory box

Communication and verification of death

General Guidance

Please read to the end of this section prior to proceeding with the assessment, to ensure understanding of the verification of death clinical assessment and appropriate communication

- Following the death of a child, an approved clinician must examine the child’s body to verify that death has occurred, and document this examination

- Families value this final examination from a known and trusted clinician, however this is not always possible

- As with any assessment or procedure, it is important to confirm the child’s identification details by checking their arm band

- Junior medical staff may benefit from the support of a consultant or senior nursing colleague when undertaking verification of death

- The clinician should liaise with the bedside nurse, and at an appropriate time-point:

- introduce themselves to the family, see communication with family/carers below

- explain the role of verification

- offer the family the choice of leaving or remaining during the examination

- During the examination, the medical officer should display gentleness and respect for the child, as they would if the child were alive

- all examinations for response should be subtle and sensitive to the feelings of the family

- some parts of the examination can be undertaken simultaneously to avoid a long examination, eg heart and breath sounds can be auscultated at the same time

- supraorbital pressure can be exerted while gently placing the hand on the child’s brow as if to take the temperature, or while raising the eyelid to examine the pupils

- nailbed pressure can be subtly undertaken while holding the child’s hand

Clinical assessment of a body to verify death

The aim of this clinical assessment is to confirm that there has been irreversible cessation of circulation or brain function

- It can be beneficial to wait a few minutes after you suspect that the child has died before performing this assessment as there can be occasional unexpected breaths, heart beats and movements in the initial minutes that follow

- Take another health professional into the room with you, when you perform the assessment. They can provide support for both you and the child’s family/carers

- Turn off the machines and monitors to remove unnecessary auditory and visual stimuli, which can be disruptive and intrusive

The exact requirements for the clinical assessment to verify death vary between states, notably the specific duration to auscultate for heart and breath sounds (see

local policies)

Usually ALL of the following are required:

- No palpable central pulse (a femoral pulse may be easier to palpate than a carotid pulse in small children)

- No heart sounds heard for the required time period

- No breath sounds heard for the required time period

- Fixed (non-responsive to light) and dilated pupils

- No response to centralised stimulus

- trapezius muscle squeeze (using a thumb and two fingers, hold and squeeze the trapezius muscles of the shoulder)

- supraorbital pressure (using a finger or thumb, apply pressure in the supraorbital groove, along the bony ridge at the top of the eye)

- No motor (withdrawal) response or facial grimace in response to painful stimulus eg nailbed pressure

In some circumstances, such as in ICU where the child is intubated and sedated, or where brainstem death needs to be verified, there are other specific processes that need to be followed

It is important to document this assessment appropriately in the clinical notes. A suggested format is as follows:

- Your name and role

- The steps of the clinical assessment and the response using wording as above

- “Confirmation of death at (insert date and time)” - this is the time that you finish your assessment

- It can be useful to document who you have notified of the death eg parents, GP, treating consultant

Communication with the family/carers

At the conclusion of the examination, the medical officer should confirm to the family/carers that the child has died and document this in the

medical record

- It is important to be clear with your communication. It is appropriate to use the words “has died”

- The use of silence to allow families to process the information you have just delivered can also be useful

- Everyone has their own way to communicate in these situations. Here are some sample phrases which may be useful:

- “Hello (insert name of parent/carer). I’m (insert name), one of the team caring for (insert name of child). I’m so sorry that we’re here in these circumstances. When you feel ready, it’s important that I briefly assess (insert name of child), listening with my stethoscope and checking their hands and eyes, so that I can confirm that they have died. Sometimes parents/carers prefer to stay in the room while this is done, and some prefer to step out for a few minutes. The decision is completely up to you. I can do this now or come back in a few minutes.”

- “(insert name of parent/carer), I’m so sorry to confirm that (insert child’s name) has died. *Can be helpful to pause here*

- “When you are ready, we can guide you through the next steps, but there’s no rush. Please take your time, don’t hesitate to ask any questions, and let us know how we can help with anything that you might need.”

Coronial vs non-coronial

There are significant interstate variations for coronial procedures

The following information provides a general overview only and must be used in conjunction with the appropriate state policy (see

Death of a child: Resources)

The coroner

- Judicial officer responsible for the independent investigation of reportable deaths, to aid reducing the number of preventable deaths and improving public health and safety

- In an investigation into a death, the coroner must find, if possible:

- the identity of the deceased person

- the cause of death

- in certain cases, the circumstances in which the death occurred

- The coroner may direct that an autopsy be held. Next of kin can request that the coroner does not direct an autopsy, but the coroner has the final say in this. Families can appeal this decision through the court (see

Death of a child: Resources)

- The coroner may or may not direct that an inquest be held. An inquest is a more detailed investigation including a public hearing and can take years to be commenced or completed

- Detailed information for health professionals outlining the coronial procedures that need to be followed are available on the coroner’s court websites

Reportable and reviewable deaths

These include, but are not limited to, the following circumstances:

- Violent, unnatural or unexpected deaths

- Accidents or injury related deaths

- Deaths where the person’s identity is unknown

- The cause of death is not known

- Deaths occurring during or following a healthcare procedure

- Deaths in care, custody, or during police operations

- Deaths of a second, or subsequent, child of a particular parent/s

- SUDI

Information required when reporting a death to the coroner

- Identification details of the deceased

- Identification details of the reporting doctor

- Where the death occurred

- Admission diagnosis

- Medical details

- Possible causes of death

- A detailed medical history is required in the event of SUDI (see

Death of a child: Sudden unexplained death in infancy, for details)

Police

- Once a death has been reported, the police may attend the hospital to collect information regarding the deceased child

- In some states, this request must go through the health service medico-legal department. It is important to follow local procedures

- Medical officers are required to provide a statement to the police. This statement can be taken at a time that is convenient. The police are not empowered to insist that it is completed at the time of notification

Coronial autopsy

- After death, a pathologist assesses all patients, reviewing the medical record and clinical investigations, and performs an external examination of the body

- The coroner decides whether a more detailed internal examination, an autopsy, is required and the coroner’s office will contact the family

- An autopsy is conducted with the same care and attention as would be done if the child were alive and undergoing a surgical procedure

- Next of kin can request that the coroner does not direct an autopsy by submitting a written objection. The coroner has the final decision regarding whether an autopsy is required

- If, as a medical professional, you think that an autopsy is very important (eg suspicion of NAI or a significant underlying diagnosis) then you should discuss this with the coroner

- See

Death of a child: Resources

Completing a death certificate

- Do NOT complete a death certificate if the death is reportable to the coroner (see Coronial vs non-coronial above)

- Death certificates should be completed as per the process for the state or territory in which the child died

- Certificates are either completed online (and copies are then printed) or on a hardcopy form,

- See

Death of a child: Resources

There are two types of death certificate:

- MCCPD (Medical Certificate of Cause of Perinatal Death), should be completed for:

- All stillborn infants of a least 20 weeks gestation

- All stillborn infants with a body mass of at least 400g (if gestation is unknown)

- All live-born infants who die before the age of 28 days

- MCCD (Medical Certificate of Cause of Death), should be completed for all other deaths not covered by MCCPD above

Note: SUDI is a reportable death and therefore a death certificate should not be completed

Clinician completing the death certificate

- A death certificate must be completed by an approved clinician within 48 hours of the death of a child

- The appropriate clinician to complete the certificate is one who:

- Has been responsible for the child’s medical care up until the time of death OR examined the child’s body after death

AND- Is satisfied that they can identify the cause of death AND is satisfied that no other circumstances are present which require the death to be reported to the coroner

- The child’s usual doctor may prefer to complete the death certificate, and should be given the opportunity to do so, if appropriate eg palliative care plan, time of day, family preference

- Where there is urgency to complete documentation, such as when there are cultural imperatives to bury the child in a short timeframe, provision of a death certificate should not be delayed

Information required for completion of the death certificate

- There is some interstate variation in the details required for certificate completion

- Information required may include:

- Epidemiological information about the child and your relationship to them

- Cause of death (see below)

- Sibling information (include legally adopted siblings and half-siblings); names, dates of birth and death, parents’ names

- Funeral director information (if available)

Cause of death

- It is important to enter the correct diagnoses on the death certificate with appropriate nomenclature

- There are 2 parts to the cause of death

- Part 1 - The medical condition or injury leading directly to the cause of death

- Part 2 - Other significant medical conditions or additional factors contributing to the death but not directly causing it

- DO NOT state the means of death, ie respiratory failure/cardiac arrest

- Additional information can be found at the

Australian bureau of statistics: Information on cause of death certification

- If you are unsure of the correct information to enter, then check with a senior clinician before completing the form

Documentation

Ensure there are adequate copies of the death certificate

- One for the child’s hospital records

- One for the funeral director

- A copy may be offered to the family but this is not a legal document

Cremation certificates

- For a body to be cremated, a specific cremation authorisation form needs to be completed by a registered medical practitioner

- The procedures vary between states (see

Death of a child: Resources). In general, the following requirements must be met by the attending practitioner:

- Sight a completed death certificate

- Agree with the cause of death

- Have no concerns that the death needs to be reported to, or reviewed by the coroner

- Have no concerns of circumstances that might necessitate further examination of the body

- Have no other reason for why the cremation should not take place

Autopsy / Post mortem

- The medical examination of a body and the internal organs after a person has died

- May be full (whole body) or limited (an area of main interest)

- Two types of autopsy:

A coroner's autopsy (see above)

- The coroner’s court will contact the next of kin

A hospital (or non-coronial) autopsy

- Can help to clarify the reasons for the child’s death

- Limited to an area of interest or to answer a specific clinical question

- Requires family consent

- A senior medical officer who has been closely involved in the child’s medical care is the most appropriate person to broach this subject with the family

- See

Death of child: Resources, for further information

Post mortem tumour donation

- The families of some children with rare brain tumours may elect to have the child’s tumour donated for research purposes after the child has died

- The child’s treating oncologist should initiate discussions if appropriate and complete consent with the family, ideally prior to the child’s death

Post mortem of a child with a suspected metabolic condition

- The families of children who die with a suspected metabolic condition may be offered urgent post-mortem investigation of the child, to facilitate diagnosis and inform future family planning

- This often includes biopsies of skin, liver and muscle, as well as blood/urine/CSF specimens

- Ideally, this initial post-mortem examination is done within 2 hours of death, to gain appropriate tissue specimens

- The child’s treating team and the metabolic team should co-ordinate this process

- Usually, consent is sought by the treating team

- The biopsies are most commonly taken by the surgical or anatomical pathology registrar

- A ‘Metabolic Autopsy Kit’ is available in some hospitals via laboratory services

- Despite a death, consideration for the referral to the Rapid-Whole Exome Sequence project should still be made if the child meets the criteria:

- Neuromuscular diseases, syndromic cardiovascular malformations, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, skeletal malformations and/or dysplasia, neonatal cholestasis and liver failure, cystic renal disease, metabolic disorders with lactic acidosis, immunodeficiency or bone marrow failure

Tissue / Organ donation

For some families, generously gifting their child’s organs provides an opportunity for finding meaning amidst very tragic circumstances

The Australian Government provides funding to all state and territory governments to maintain an organ and tissue service. This is known as the

Donate Life network

- It is important to remember that donation can still be considered even in the setting of a coroner’s case

- The consideration of organ and tissue donation should never impact upon the overall care you provide the child and their family

- Never assume that a child would not be eligible, or that a family would not be interested, without contacting your hospital donation specialist, often the oncall donation specialist co-ordinator at Donate Life. See

Death of a child: Resources

- The types of tissues and organs that can be considered for donation will depend on the child’s age, size and clinical circumstances

- Tissue donation: the donation of tissues such as eyes, heart valves, skin, bone and tendons for the purpose of transplantation into others. These can be retrieved within 24 hours after death is declared

- Organ donation: the donation of whole organs such as heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, pancreas and intestines for the purpose of transplantation into others. Only people who die in an intensive care unit on a ventilator can donate whole organs

Other considerations

Notification of relevant people

It is important to notify key staff involved in the child’s care, along with those who are involved in the family’s care, so that ongoing support can be provided

These include:

- The child’s GP

- The family’s GP (if different to the child’s GP)

- The child’s usual paediatrician

- The doctor who referred the child to the hospital (if different to above)

- Other specialists actively involved in the child’s care, including the palliative care team

- Other clinicians eg maternal child health nurse/obstetrician

It is useful to contact The Australian Childhood Immunisation Register (if the child is less than 7 years of age) so that the family are not contacted about upcoming immunisations (phone 1800 653 809 or email patient details to

acir@humanservices.gov.au)

It is important to record the child as deceased in the hospital records, and to ensure that unnecessary future appointments are cancelled

- It may be beneficial to keep a single appointment with the child’s long term doctor, to allow the family to follow up, see Supporting the family below

Discharge summaries

- A thorough yet concise discharge summary is particularly important in the case of a death, many people will rely on it for information

- The discharge summary is likely to be read by family members, as well as health professionals involved in the child’s care

- It is often junior members of the team who write discharge summaries, it is appropriate to seek senior input

Checklists

- Can be useful to ensure that all the correct processes have been completed

- Often embedded into local hospital procedures or electronic medical records

Supporting the family

- Ensure the involvement of social workers and bereavement counsellors

- It is essential that a firm arrangement is in place to ensure that the family will be offered a chance to discuss their child's death with someone

- Never assume that the family don’t need a follow up, or that they will call if they do need one

- The optimal timing can vary according to the family but making contact at 2-4 weeks is often appropriate

- The best person to do the follow up will vary from case to case, but it should be a clinician who has established a relationship with the family either before or at the time of the child’s death, sometimes this will be you. Discuss with the others in the extended team to decide who is the most appropriate person, and record the decision in the child’s medical notes

- Never assume that someone else will organise the follow up. Organise it yourself, or make sure that another member of your team has definitely made these arrangements as per local hospital procedures

Caring for yourself

- Everyone reacts differently to these sorts of events. Some people might find the event stressful or significantly distressing, others might find that they feel nothing at all. These reactions can apply equally to both new and experienced staff

- It is normal to experience grief at the death of a child in your medical care, and it can often be helpful to realise that many of your colleagues have experienced similar feelings

- It is important to acknowledge how you feel and to seek supports as, and when you feel is right for you

A few suggestions

- Take some time alone to think about what has happened. It's OK to cry

- Sit and have coffee and a chat with the others involved in the child's death

- Thank your medical, nursing and social work colleagues for their help in the child's death. Some positive feedback will help everyone

- Maybe finish your shift early, if practical to do so

- Talk to someone you feel comfortable with about the situation: the consultant on your team, a mentor, another colleague. Talking through the events and how you feel can be helpful

- Find out about de-briefing sessions, these may be co-ordinated by any member of the team. If there is not one organised, consider speaking to an experienced colleague who could co-ordinate a session for those who were involved in the child’s care.

- Talk to someone outside of your group of colleagues. Many hospitals have a staff support service, such as the Employee Assistance Program, which can provide assistance in these circumstances. Your own GP can also be a source of support

Parent information

National resources

Other useful resources

Last updated September 2022