Table of contents will be automatically generated here...

Introduction

Fractures of the thoracic spine account for 25-30% of all spine injury in children, while lumbar fractures account for 20-25%.

Injuries to the thoracic spine and the thoracolumbar junction have a higher incidence of spinal cord injury, with neurologic deficit seen in up to 40% of cases.

Multiple-level injuries are seen in 30-40% of children with thoracic or lumbar spine fractures.

Fractures of the lower thoracic and upper lumbar spine have associated small bowel and visceral injury in up to 50% of cases.

Road traffic accidents and falls account for most of the injuries, but non-accidental injuries to these regions do occur.

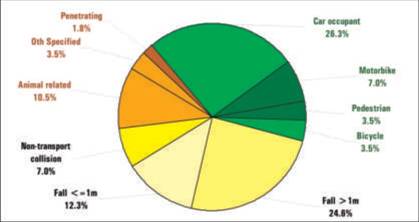

Over the three-year period from July 1, 2000 through June 30, 2003, 89 thoraco-lumbar spine injuries were recorded in 57 patients at the RCH. A breakdown of these admissions by injury cause is given in Fig 1, while a breakdown of injuries sustained is

presented in Table 1.

Fig 1. RCH thoraco-lumbar spine injury admissions by mechanism, 20002003 (n=57)

Table 1. Thoraco-lumbar spine injuries by injury type

47% of patients with thoraco-lumbar spine injuries had an injury to one or more other body regions. A significant number of these (10 of 27 patients) had an abdominal injury with or without further injuries, usually as seat-belt injury in a motor vehicle

accident.

In all aspects of trauma

management, the primary survey is the first

priority

Primary survey

Airway with c-spine stabilisation (see chapter 1.3) Breathing (see chapter 1.4) Circulation (see chapter 1.5)

Assessment of the spine should

take place in the secondary survey after the airway, breathing and

circulation have been assessed and stabilised.

History

- Mechanism of injury is important in identifying the risk of thoracic or lumbar spine injury.

- The presence of pain in the back makes injury more likely; however absence of pain does not exclude injury.

Clinical examination

Should focus on:

- Tenderness and signs of bruising or deformity over the spine.

This is assessed by log-rolling the patient while spinal immobilisation is still in place.

- A search for signs of spinal cord or cauda equina lesions should also be made.

Any patient who has pain or tenderness over the spine

should have the spine evaluated by radiography.

Patients at risk of having thoracic or lumbar spine (and

cervical spine) injuries missed:

- Those without pain or tenderness, but with altered conscious state; -Those with other significant injuries.

As multi-level injuries are common, any child with a proven cervical spine fracture or spinal cord injury should have the entire spine imaged with plain radiographs.

Radiology

Indications for thoracolumbar spine xrays

- Pain in the thoracic or lumbar region.

- Tenderness of the spine in the thoracic or lumbar region.

- Significant bruising or deformity of the spine.

- Altered conscious state.

- Proven fracture in another region of the spine.

Radiographic evaluation

Radiographs should be taken on any child who is at risk of having a thoracic or lumbar spine injury after clinical evaluation.

The standard views for both areas are:

- The anterior-posterior radiograph, and

- The lateral film.

- A swimmer's view may be needed to visualise the first two thoracic vertebrae, as the shoulders often obscure the upper thoracic spine.

The films should be evaluated by:

- Following the anterior and posterior vertebral body lines and the spinolaminar line on the lateral view.

- These three lines should have a parallel course.

- The height of each vertebral body should be assessed anteriorly and posteriorly

- A difference of more than about 3mm should be treated as pathologic.

- On the AP view the para-spinal lines should be closely inspected to detect evidence of paraspinal haematoma. -The posterior elements should be visible through the vertebral body and should be in alignment. - In AP look at gap between the spinious processes

There are a number of features on the radiographs, which indicate an unstable fracture:

- Vertebral body collapse with widening of the pedicles;

- Greater than 33% compromise of the spinal canal by retropulsed fragments;

- Translocation of more than 2.5 mm between vertebral bodies in any direction;

- Bilateral facet joint dislocation;

- Greater than 50% anterior compression of the vertebral body associated with widening of the interspinous space. [25]

While most thoracic and lumbar spine fractures are diagnosed on initial plain radiographs, these films often do not provide enough information on the extent of the injury and a CT scan of the region is usually obtained to elucidate the full extent of the injury. MRI

will be needed to visualise all ligament and spinal cord involvement.

Management

- Must start with care of the airway, breathing and circulation.

- Only once these areas have been stabilised should management of the spine proceed.

- While the patient is being stabilised, the spine should be maintained in alignment and the patient moved via log-rolling.

- A thorough assessment and investigation of the abdomen and chest is mandatory for all patients with significant thoracic and upper lumbar spine injuries,

- Injuries to the pelvis must not be forgotten with lumbar spine injuries.

- As many of these injuries are associated with intra-abdominal injuries, an ileus is common and a nasogastric or orogastric tube should be inserted.

Consultation with a paediatric orthopaedic surgeon or neurosurgeon should be sought for the definitive care of the injury.