Table of contents will be automatically generated here...

Key points

- Children

are particularly vulnerable to ocular trauma.

- Serious

eye injuries can be under appreciated in the child who has a painful eye,

blurred vision or extensive subconjunctival haemorrhage.

- Ensure

prompt and adequate analgesia.

- If

a ruptured globe is suspected or identified: stop examination, place an eye

shield over the eye to avoid extrusion of ocular contents, obtain a CT Orbit

(if there is a history of a possible foreign body), keep nil by mouth and refer

urgently to ophthalmology.

Introduction

Paediatric ocular trauma is a cause of significant

morbidity, with up to 280,000 hospital admissions worldwide per year. [1]

However, hospital admissions only account for around 5% of total eye injuries –

so it has been estimated that worldwide there are around 6 million episodes of

eye injury in children.[2] Open globe injury (ruptured globe due to

blunt trauma, or laceration due to a penetrating injury) is a severe form,

which, in children, is most commonly caused secondary to penetration with a

sharp object whilst at home.[3]

Children account for between 20 and 59% of all eye injuries[4]. They are more predisposed to eye injury due

to their developing physical coordination, limited ability to detect

environmental risks and a more vulnerable facial morphology.[5] The outcome of paediatric eye injuries is

worse than that of adults due to their visual immaturity, increased years of

visual loss and potential for amblyopia.[5] Most paediatric eye

injuries (66.2%) occur during play – predominantly whilst at home under

supervision of parents / caregivers (47.7%), but often whilst at school /

nursery (24.4%).[2] Sharp

instruments are the most common cause of injury, followed by plants, animals,

toys or sports equipment.[2] In the Australian context, it has been

estimated that sports-related eye injuries make up 11% of all paediatric eye

injuries. [6] Boys are twice as likely to sustain a significant eye

injury compared to girls.[2]

Features of ocular trauma history and examination (see also RCH Clinical Practice Guideline: Acute eye

injuries in children and RCH Clinical Practice Guideline: Penetrating eye injury)

Serious eye injuries can be under-appreciated when children

present with a painful, blurred vision or an extensive subconjunctival

haemorrhage. In all traumatic eye

injuries consider the following principles: [7]

- Manage (other) life threatening injuries

- Ensure the structural integrity of the globe

- Assess vision in the injured AND the uninjured

eye

- Seek ophthalmology consultation where required

Where an open globe injury is suspected it is important to

minimise child distress – as crying can raise ocular pressure leading to

extrusion of intraocular contents.

The key diagnoses to seek and identify are:

- Open globe injury – ruptured globe or

penetrating laceration

- Foreign body – corneal or intra-ocular

- Large hyphaema

- Retinal detachment

- Corneal burns – chemical or thermal

History

Symptoms

- Pain – at rest or with movement

- Vision - loss (ongoing or temporary, global or

central) or blurring or other disturbances such as flashes (associated with

retinal detachment) or floaters (associated with intra-ocular injury)

- Foreign body sensation – pain with blinking or

moving eye

- Discharge from the eye

- Photophobia

Mechanism

of Injury

- Risk of high velocity penetrating injury – small

projectiles at high velocity have a higher risk of penetration - eg playing

with air-rifle, near lawn-mowers, using metal grinders or other power tools,

hammering

- Risk of low velocity penetrating injury – eg

running with sharp object, catching eye on sharp thorn or plant material

- Risk of blunt injury -eg sports injury such as squash ball to

orbit, motor vehicle accident (be aware an airbag ocular injury to a front seat

passenger can be a combination of a blunt or penetrating injury with a chemical

burn)

- Risk of chemical or burn injury to eye – eg

flash burn to face, playing with detergent pods. Alkali burns are generally more dangerous

causing liquefactive necrosis.

Other

- Any

first aid already provided?

- Glasses

or eye protection worn?

- Presentation

maybe delayed so ask for history over the previous few weeks.

- History

of previous trauma to eye(s).

- Associated

trauma/injuries.

Examination

If adequate examination is not possible due to either the

child’s age or level of cooperation, specialist assistance should be

sought. Where there is significant

concern for an open globe injury, it is prudent not to overly distress the

child through multiple attempts at examination, as crying can lead to an

increase in intraocular pressure, with the resultant extrusion of intraocular

contents. Early referral to ophthalmology

is appropriate in these cases – along with administration of appropriate

systemic and topical analgesia and anti-emetics. Ondansetron is an appropriate option, as it

has a lower risk of causing a dystonic reaction. Opiate analgesia may lead to nausea and

vomiting which can increase intra-ocular pressure – so consider pre-treating

with anti-emetics if you think strong analgesia is required.

Even when open globe injury is not suspected, appropriate

analgesia, oral or intranasal analgesia as well as topical (single drop of

preservative free local anaesthetic – eg amethocaine 1%) should be given to

reduce pain and aid the child’s ability to tolerate examination. However, it is worth noting that local

anaesthetic is itself a direct epithelial toxin, so it shouldn’t be used

repeatedly (and patients should not be discharged with topical local

anaesthetic). A child life specialist

(play therapist) may also assist in helping the child relax during an

examination. Be aware that when a child

has suffered a monocular injury, occluding the good eye may increase their

distress (as they will no longer be able to see).

Where a burn is suspected, first aid should take precedence

over a complete examination. This

consists of copious irrigation (after local anaesthetic and systemic analgesia

given). In some cases the patient may

need to be sedated to facilitate first aid treatment.

A complete examination of the eyes requires examination of:

1.Visual acuity in both the injured and uninjured

eye

- Use age appropriate charts and the patients

normal corrective lenses or pinhole

- Snellen chart from school age

-

“E” chart from about 3 years old

-

Kay picture book – ages 2-3

A difference of more than 2 lines on an eye

chart is likely to be significant. If unable to read a chart, check the patient can

count fingers or confirm light perception

2.Eye movement

- Check the child can look in all directions

- Check for diplopia or pain with eye movement

- In trauma, an orbital floor fracture can lead to

reduced upward gaze (entrapment of inferior rectus)

3.Visual fields

- Four quadrant testing in older children

- Traumatic visual field loss is usually grows,

however, subtle changes may occasionally occur with retinal detachment and

intra-ocular foreign bodies

4.Pupils

- Check size, symmetry, shape and reactivity

- Look for both a direct and indirect pupillary

response

-

A relative afferent pupillary defect may suggest

an increase in retrobulbar pressure (ie a retrobulbar haemorrhage secondary to

trauma), optic neuropathy or severe retinal detachment.

5.Lids, conjunctiva and sclera

- Look for swelling, chemosis, ptosis, ecchymosis

and lacerations

- Evert the lids to look for foreign bodies on the

underside

- If there is a laceration on the eyelid – check

to see if it extends through the tarsal plate – maintain a high level of

suspicion for globe rupture in the presence of any eyelid laceration

- Look for a subconjunctival haemorrhage – whilst

many are benign, a localised haemorrhage may suggest penetrating injury. An

inability to visualise the posterior extent of a subconjunctival haemorrhage

may suggest an orbital or base of skull fracture. In infants, subconjunctival haemorrhage may

be a sign of non-accidental injury.[8]

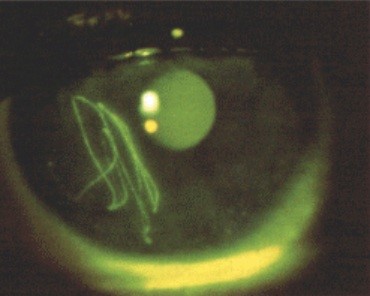

6.Cornea, Anterior Chamber and Iris

- Look for a hyphaema – this is blood in the anterior

chamber – mild cases may only have suspended red blood cells seen in the

anterior chamber.

- Check there is no iridodialysis – a disinsertion

of the iris from the sclera

- Look for corneal abrasions and foreign bodies

-

Application of fluroscein dye will help identify

abrasions

-

Vertical scratches on the cornea indicate the

likely presence of a foreign body under the upper eyelid

7.Fundus

- Look for red reflex, assess the optic disc, the

macula and periphery

- A red reflex may be diminished due to vitreous

haemorrhage or lens opacity

- Retinal detachment may be seen as a grey flap

- Check for retinal haemorrhages and papilloedema

8.Palpate the orbital rim

- Assess for bony fractures

- Check for paraesthesia in the infra-orbital

nerve distribution

9.Consider assessing intraocular pressure

- In the context of trauma, and intraocular

pressure of <10 will indicate a potential globe injury

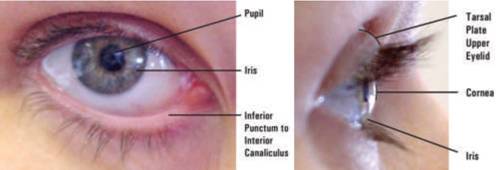

Make sure to document the location of injuries according to the external eye anatomy as shown in Figure 1.

Fig 1: External anatomy of the eye

Ocular Trauma

Blunt

- Intraocular

contents are at risk of considerable damage by blunt force trauma.

- Orbital

bony wall is relatively thin thus susceptible to fracture from transfer of

mechanical energy across globe.

- Potential

Injuries:

- Lid injury

- Orbital blow-out fracture

- Retrobulbar haemorrhage

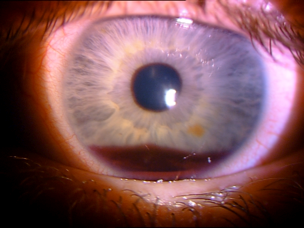

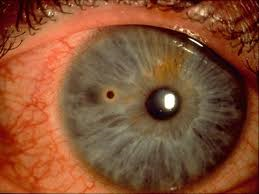

- Hyphaema - this refers to blood in the anterior chamber and is secondary to a tear in the iris and / or ciliary body. (see Fig 2.)

- Traumatic mydriasis – associated with iris

sphincter tears.

- Iridodialysis - this is the detachment of the iris root from its insertion site at the ciliary body. It can lead to a "D-shaped" pupil.

- Lens dislocation

- Cataract

- Vitreous Haemorrhage

- Retinal detachment

- Traumatic Iritis - or inflammation of the anterior chamber post blunt trauma is common in children. Examination reveals anterior chamber cell and flare, there may also be a poorly reactive pupil, with sustained miosis.

- Ruptured

Globe – (see below).

- Consider

CT Orbit +/- brain when concerned about blowout fracture or head injury.

- Immediate

Ophthalmology consultation is indicated in:

- Actual Globe or corneal perforation

- Concern of globe rupture

- Orbital haemorrhage

- Lens dislocation

- Visual changes

- Lid laceration

Fig 2: Hyphaema after blunt trauma

Open globe injury

Open globe injury refers to a full-thickness mechanical

injury to the cornea and/or sclera. The

two broad types are[3]:

- Ruptures – which result from blunt trauma such

as a ball striking the orbit and

- Lacerations – which are caused by a sharp object

entering the globe. Lacerations are

further classified as:

- Penetrating injuries – where there is a single

wound to the globe - for example from point of knife

- Perforating injuries – where there are separate

entrance and exit wounds

- Intra-ocular foreign body – where there is an

entrance wound with a foreign body within the globe – for example from a metal

splinter in a grinding injury

Penetrating injuries are the most common, followed by

intraocular foreign body injuries, then rupture, with perforating injuries

being the least common. The most common

location for injury is at home – especially for pre-school children. Older

children are increasingly likely to sustain an open globe injury outside of the

home.[9] A common cause of injury is

kitchen items, followed by sticks, pencils, metallic and elastic objects. Older children may suffer projectile injuries

through hammering or the use of paintball guns / air rifles.

If

penetrating eye injury is suspected:

- Do NOT force the eyelid open as pressure on the

lids may cause extrusion of ocular contents.

- Do NOT attempt to remove a protruding foreign

body from the globe.

Symptoms

- Pain

- Decreased visual acuity

Signs

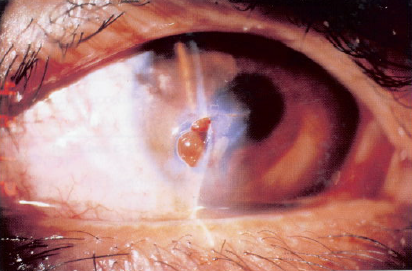

Anterior signs: peaked or irregular pupil, iris

prolapse, corneal laceration, hyphaema, extensive subconjunctival haemorrhage and chemosis (conjunctival swelling).

Posterior signs: poor red reflex (vitreous

haemorrhage), decreased vision, uveal prolapse,

Treatment

- Keep patient fasted in anticipation of theatre.

- Adequate analgesia with antiemetics as vomiting

may increase intra-ocular pressure.

- Sit patient upright where able (may depend on

ability to clear C-spine)

- Shield the eye, be careful when shielding not to

press on the eye.

- Do Not instil drops or ointments into eye.

- Prompt discussion with ophthalmologist

- CT scan of orbit to investigate for ocular

foreign body.

- Commence ciprofloxacin and check tetanus status.

Fig 3. Corneal laceration with prolapse of iris following penetrating trauma

Orbital blow out fracture

These occur following high

energy blunt traumas (e.g. hit with ball, bat or fist) that create an increase in intra-orbital pressure.

Symptoms

These include pain and diplopia (especially on vertical movement), tenderness, eyelid

swelling. Nausea +/- vomiting and pain on eye movement may occur if there is entrapped

muscle.

Signs

Ptosis, tenderness, restricted eye movements (especially on vertical

movement), crepitus of lower lid. The globe may appear "enopthlamic" (recessed into the orbit) or displaced downwards. There may also have associated ocular injuries secondary to blunt trauma – (see above). Infraorbital nerve involvement leads to reduced sensation

to cheek, upper teeth and gums of affected side.

Fig 4: A 4yo child with right orbital 'blow out' fracture associated with entrapment

Management

- CT scan with coronal cuts is the investigation of choice to assess the integrity of bony orbit.

- Refer to Ophthalmology and Plastic Surgery units.

Fig 5: Isolated right orbital floor fracture

Non accidental injury (NAI)

Non-accidental

causes are a common and significant cause of ocular trauma in paediatrics.

Red

Flags

- Unexplained periorbital haemorrhage, especially

in setting of other injuries.

- Poorly or unexplained mechanism of injury.

- Any burns in a small child.

Detailed

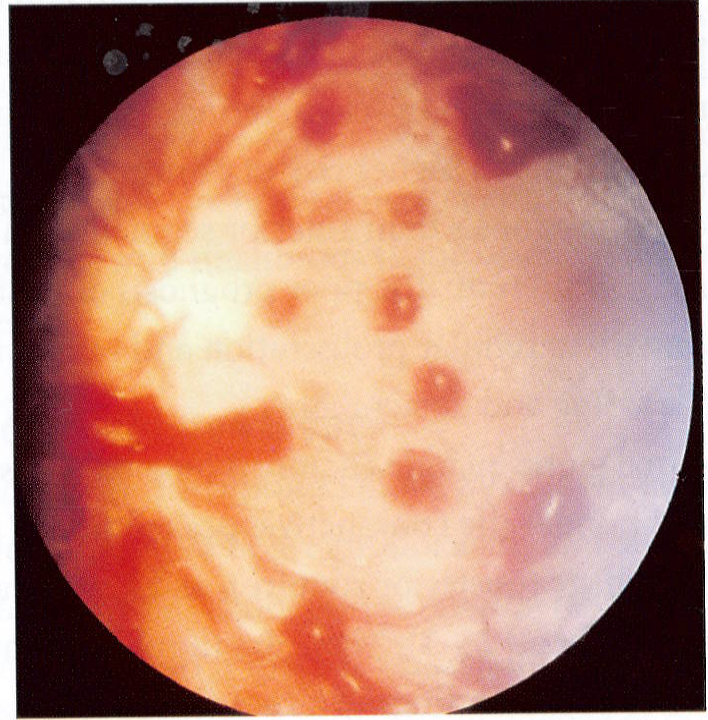

fundoscopy by an ophthalmologist is required in all cases of suspected NAI, and

should be considered in all cases of head injury of infants and young children.

Key

pathological findings include: Extensive multilayered (retinal, pre-retinal and

subretinal) haemorrhages in all four quadrants with possible vitreous

haemorrhage

Fig 6: Retinal haemorrhages following non-accidental injury

Chemical burns

Acid

and alkaline solutions that come into contact with the eye surface can cause

considerable damage and are a true ophthalmic emergency. Immediate

irrigation prior to arrival in ED is ideal, if this hasn’t occurred it should

be performed on arrival to ED

To

facilitate irrigate of the eye:

- Instil local anaesthetic drops to affected

eye(s)

- Irrigate with normal saline - minimum one litre, aim to include under

eyelids and conjunctival fornices.

- If possible use a Morgan Lens otherwise continue

irrigation using a gloved hand to retract lids as possible.

- Review patient’s pain regularly, re-instil local

anaesthetic drops 10 minutely as required.

- After one litre of irrigation, review the

eye. Wait 5 minutes after ceasing

irrigation to check eye pH using universal indicator paper, aim for pH equal to

unaffected eye or if both eyes are effected then aim for pH close to neutral;

discuss with specialist and continue irrigating if outside this range.

- Severe burns will usually require a minimum of 30

minutes of irrigation.

All

chemical burns should be assessed by ophthalmology after wash-out.

Alkaline

burns are especially damaging as the base solution will denature proteins, lyse

cell membranes which enhances penetration into the eye and increases further

damage.

Acid

solutions also cause severe damage, however acid solutions largely precipitate

proteins which can limit the area and depth of necrosis.

Corneal abrasions and foreign bodies

One of the most common paediatric ocular presentations to

emergency:

- Present with (often sudden onset) painful and

watering red eye.

- Use slit lamp, if available and child can

tolerate, or ophthalmoscope for examination.

- Examine both pre and post instillation of 2% fluorescein

drops to identify foreign body and potential corneal abrasion by the child inadvertently

rubbing their eyes.

- Always evert lids if possible. Most subtarsal

foreign bodies will be close to the eyelid margin.

Precautions

- Attempt to remove the foreign body as retained matter can

cause issues: infections if organic, rust rings if metallic.

- Upon successful removal of foreign body and in setting of

corneal abrasion, discharge with topical antibiotic drops (e.g. chlorsig) and

consider antibiotics ointment nocte as lubricating effects are soothing and can

help with sleeping.

To remove the foreign body

- Instil topical anaesthetic drop (e.g. tetracaine

hydrochloride 0.5%); warn the patient the drop will sting briefly.

- Attempt to remove foreign body with a moistened cotton

bud.

- If unsuccessful and if child is able to tolerate

sitting still at a slit-lamp, use a 25 gauge needle with bevel up to remove

corneal foreign bodies.

- If still unsuccessful after 2 attempts, cease

and contact Ophthalmology.

Fig 7: Corneal foreign body - metal fragment with rust ring

Fig 8: Linear corneal abrasions suggestive of a subtarsal foreign body

Lid lacerations

An

eyelid laceration should be treated as a potential penetrating injury until

proven otherwise. Superficial

laceration away from the lid margin, may be safely closed by standard suture

techniques. However any laceration that

involves the eyelid margin should be repaired by an ophthalmologist given the

complex lid anatomy (tarsus, grey line, medial and lateral longitudinal tendons

and canaliculus).

Lacerations,

even minor, to the medial canthus may involve the canaliculus and thus should

be referred.

Treatment

- Control the bleeding with elevation of head and direct pressure. Avoid pressure to the globe.

- Examine eye for penetrating injury once lid-bleeding is controlled.

- Suspect canalicular injury, if the medial part of either the upper or lower eyelid is involved. In this situation, early involvement of the Ophthalmology Unit is required.

References:

- Abott J, Shah P.

The epidemiology and etiology of pediatric ocular trauma. Surv

Ophthalmol. 2013; 58(5):476-485

- Sii, F et al. The UK Paediatric Ocular Trauma

Study 2 (POTS2): demographics and mechanisms of injuries. Clinical Ophthalmology 2018:12:105-111

- Xintong, L. et al. Pediatric open globe injury: A review of the

literature. K Emerg Trauma Shock

2015;8(4):216-223

- MacEwen, CJ. Et al. Eye injuries in children: the current

picture. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:933-936

- Hoskin, AK. Et al. Eye Injury Prevention for the Pediatric

Population. Asia-Pacific J Ophthalmol

2016 5(3):202-211

- Hoskin AK et al.

Sports-related eye and adnexal injuries in the Western Australian

paediatric population Acta Opthalmologica

2016;94:e407-e410

- Root, JM et al.

Nonpenetrating Eye Injuries in Children. Clinical Pediatric Emergency Medicine 2017;18(1):74-86

- DeRidder, CA et al. Subconjunctival Hemorrhages in Infants and

Children: A sign of nonaccidental Trauma. Ped

Emerg Care 2013;29(2):222-226

- Gunes et al.

Characteristics of Open Globe Injuries in Preschool children Paediatric Emergency Care 2015;31(10):

701-703