Table of contents will be automatically generated here...

Introduction

Significant abdominal injuries are relatively uncommon in childhood trauma. However, the signs can be difficult to interpret in a scared, traumatised child. A high index of suspicion is needed, based on the child's history, to identify these injuries.

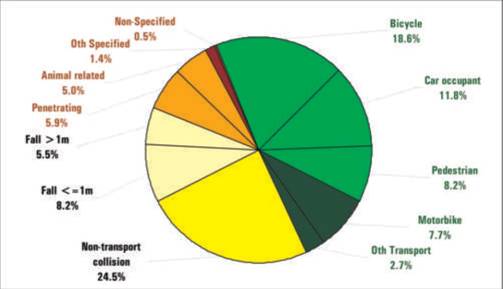

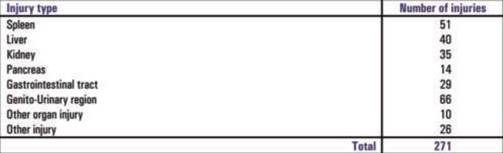

Over the three-year period from July 1, 2000 to June 30, 2003, 271 abdominal injuries were recorded in 220 patients at the RCH. A breakdown of these admissions by injury cause is given in Fig 1, with a breakdown of type of injuries sustained presented in Table

1

Fig 1. RCH abdominal injury admissions by mechanism, 2000-2003 (n=220)

Table 1. Abdominal injuries by injury type

30% of patients with abdominal injuries had an injury to one or more other body regions.

How children are different

- Abdominal organs are relatively susceptible to injury because:

- The relatively small size of the patient allows a single impact to injure multiple organ systems.

- The abdominal wall is relatively thin (less muscle & less subcutaneous fat), so it provides less protection.

- The ribs are more pliable, providing less protection.

- The liver and spleen take up a larger proportion of the abdominal cavity.

- The diaphragm is more horizontal, tending to push the liver and spleen lower below the rib cage.

- The bladder in babies is an intra-abdominal organ.

- Adult protection systems, such as seat belts, are often ill fitting or worn incorrectly, causing deceleration injuries to the upper abdomen.

In all aspects of trauma management, the primary survey

is the first priority

Primary survey

Airway with c-spine stabilisation (see chapter 1.3) Breathing (see chapter 1.4) Circulation assessment and management (see chapter 1.5)

Secondary survey

Perform a thorough back & front / head-to-toe examination for other injuries.

Abdominal Organs at risk

- Solid organ injury - Liver, Spleen, Pancreas

- Intestinal injury: -Stomach -Duodenum -DJ flexure -Small & large bowel

- Genito-urinary injury -Kidney -Bladder -Urethra

Assessment

History

Patients at risk include those with:

- High impact / deceleration injuries;

- Direct blows to the abdomen;

- Evidence of injuries above and below the abdomen, suggesting the abdomen is unlikely to have been spared.

- Seat-belt injuries (duodenum or pancreas).

- Bicycle handlebar injuries to upper abdomen (duodenum or pancreas).

- Straddle injuries, astride a bar or beam (perineum, vagina or urethra).

- Penetrating injury to chest, abdomen or pelvis, especially if the entry and exit sites are above and below the diaphragm.

- Injuries suggestive of child abuse. (see chapter 1.21)

Examination

The abdomen of the frightened child is very difficult to assess. The best clinical yield of information occurs in the presence of the child's carers, and when every effort is made to help calm and relax the child with adequate explanations, reassurance and

analgesia.

- Any signs of circulatory compromise, especially with a history suggestive of abdominal injury, should prompt assessment of the abdomen and pelvis as part of 'Circulation' in the primary survey.

- Marks, bruises or wounds to the abdomen. Look for specific signs, such as seat-belt or handlebar marks in the upper abdomen. Check front and back.

Lap belt bruising

- Abdominal distension suggests blood, fluid, intestinal perforation or acute gastric distension.

- Abdominal tenderness significant, especially if over the liver, spleen or renal angles.

- Generalised guarding suggests peritonitis, usually a sign of massive bleeding or perforation.

- Pelvic instability or tenderness avoid repeated examination, which may cause blood loss.

- Blood at the urethral meatus suggestive of urethral trauma.

- Inspection of the back & perineum is essential, but needs to be explained and done calmly.

PR or PV examination is rarely required, and simply

traumatises the child. Should only be considered if evidence of

trauma to the area.

General management

Even where there is significant disruption of solid organs with haemodynamic insatiability conservative management is usually possible with adequate resuscitiation.

Conservative management implies close and continuous observation, and is not the easy option. It should only be undertaken only in an institution where rapid access to surgical intervention is available at all times.

- ABCDE

- Fluid resuscitation with 20 ml / kg normal saline or Hartmans.

- Second bolus of fluid as above, if required (see chapter 1.18).

- If further boluses of fluid are required, use blood.

- Immediate further SURGICAL review.

- Pass orogastric tube.

- All patients with free intraperitoneal air require a laparotomy.

- All penetrating wounds should be explored in theatre under general anaesthetic (see chapter 1.9).

- Intra-peritoneal bleeding is not an indication for laparotomy, so Diagnostic Peritoneal Lavage (DPL) has no significant role in children.

- Children with a history of significant trauma or high impact trauma should be admitted for observation even in the absence of examination findings.

The vast majority of solid organ injuries (i.e.

liver, spleen, pancreas & kidney) can be treated

conservatively

Orogastric/Nasogastric considerations

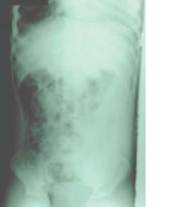

Gastric dilation and NO gastric tube

Note the severe gastric dilation in this intubated patient, compromising the ventilation, who does not have an orogastric tube. Once the tube was passed the dilation resolved and the patient stabilized.

All patients undergoing CT scan should have an OG/NG tube

prior to the investigation

- This reduces the risk of vomiting while in CT,

- It protects against the risk of acute gastric dilatation.

Acute gastric dilatation can occur with relatively minor

abdominal trauma

When in doubt, do not hesitate to place an orogastric/ nasogastric tube in cases of paediatric trauma. It should always be considered prior to transfer of the child with abdominal injury.

Acute gastric dilatation should also be considered in

the differential diagnosis

Where a child has abdominal pain and distension associated with signs of shock following abdominal or major trauma. Even when the abdominal trauma may not appear severe in nature.

Investigations

- Bloods, FBC, lipase/Amylase & LFTs, Crossmatch, BM

- Urine analysis: All abdominal trauma patients should have urine analysis done.

- CT scan is the imaging modality of choice. Intravenous contrast is essential. Patients must be stable enough to move to CT scan.

- X-ray. Only require supine and decubitus lateral / right-side-up abdominal X-rays if there is a suspicion of intestinal perforation.

- U/S. This can be used for imaging of solid organ injury but a CT scan remains the gold standard .It can also be used to see if there is free fluid in the peritoneal cavity. However, a negative study does not rule out injury.

- Fast U/S . Is not routinely undertaken in the paediatric setting. This is because evaluation of the fluid volume present in the abdomen can be difficult and ultimately the presence of blood is not an indication for surgery. The need for a

laparotomy in blunt abdominal trauma cases, as previously stated, relates largely to clinical response to aggressive resuscitation and the nature of the organs injured in the trauma.

- IVP. Can be used to assess renal trauma but the kidney can usually be assessed with IV contrast at the time of CT scan.

Diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) has no significant role in children

Management specific

| 1. |

Spleen |

6. |

Kidney |

| 2. |

Liver |

7. |

Bladder |

| 3. |

Pancreas |

8. |

Urethra |

| 4. |

Intestine |

9. |

External genitalia |

| 5. |

Duodenum |

|

|

1. Spleen

- Isolated splenic injury in almost all cases can be managed conservatively with resuscitation and close observation.

- Patient care involves

Acute

- I.V. access with aggressive initial resuscitation with IV fluids,

- Cross-matching blood,

- Regular nursing observation,

- Continuous monitoring (possibly in High dependency unit)

- Repeated clinical examination

Ongoing

- Bed rest until pain settles

- Length of stay related to clinical stability, and the resolution of signs and symptoms.

- Follow-up repeat ultrasound scan may be undertaken at 3 months but not essential if clinically well.

Splenic rupture

Indications for laparotomy

- Haemodynamic instability - despite resuscitation.

- Transfusion requirements of more than 40 ml / kg during the period of acute resuscitation4

Late problems

Late rupture. This is a risk, but there is no clear evidence of it being linked to insufficient bed rest, or to returning too early to unrestricted activity. The adult literature suggests that late rupture occurs in about 6% of patients.1 However, it is only

rarely reported in children.2,3,4 Healing of the spleen can be documented radiologically on ultrasound, and appears to correlate closely with the severity of rupture.3 Studies in Pittsburgh have shown that healing takes from 3 weeks in minor splenic injury,

to 20 weeks for a severely shattered spleen.3 However, it is not known whether this constitutes full physiological healing, or how it relates to late rupture.

- A sensible protocol is strict bed-rest until the abdominal pain subsides, followed by restricted activity for 3 months, followed by return to full activity. (Though some reports suggest 6 weeks may be sufficient)

- The most important issue is to brief the parents fully on the risks of late rupture, and the need to return to hospital urgently if symptoms of pain or collapse occur.

Delayed rupture can still be treated conservatively, following the same protocol as the acute injury.

Loss of splenic function: Studies in adults demonstrate that approximately one-third of the spleen is needed for normal immunological function3 . Assess the percentage of spleen remaining on the initial CT scan, and repeat the splenic ultrasound. Look for Howell Jolly bodies on blood film. If

suspicious, immunise & start on oral Pen V.

References

- Delayed splenic rupture: real or imaginary? Farhat GA, Abdu RA, Vanek VW: American Surgeon, 1992: 58; 340-345

- Observation of splenic trauma: When is a little too much? Brown RL, Irish MS, McCabe AJ, Glick PL, Caty MG. Journal of Paediatric Surgery. 1999: 1124-1126.

- Computer tomography grade of splenic injury is predictive of the time required for radiographic healing. Lynch JM, Meza MP, Newman B, Gardner MJ, Albanese CT. Journal of Paediatric Surgery, 1997: 32; 1093-1096.

- Ruptured spleen. When to operate? Wesson DE, Filler RM, Ein SH, Shandling B, Simpson JS, Stephens CA. Journal of Paediatric Surgery. 1981: 16; 324-326.

2. Liver

At least 80% of blunt liver injuries can be treated conservatively

- Conservative management involves aggressive resuscitation and close observation as previously detailed.

- When fluid resuscitation exceeds 40mls/kg in 2 hrs with ongoing instability surgical intervention must be strongly considered.

- Unlike surgery for splenic trauma, surgery on the injured liver is complex, with a high morbidity and mortality.

- If stability is obtained considered opinion recommends transferring the child to a dedicated paediatric trauma service for close monitoring and obtaining a CT scan.

- If the patient is too unstable to transfer, a laparotomy with packing of the liver is all that should be attempted before transfer.

- CT scan with intravenous contrast is ideal if the surgeon is to have any chance of identifying the problem at the time of laparotomy.

- There remains a risk of late bleeding from the injured liver €" a suggested plan for those with a major injury is of strict bed rest until the abdominal pain settles. Then with restricted activity for a further 3 months.

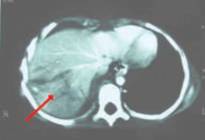

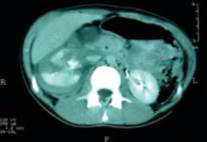

Liver injury treated conservatively

Late problems Continued Bile Leak evidenced

by

-

Slowly increasing abdominal distension,

- Rising bilirubin

- Ultrasound evidence of increasing ascites

Investigations include a HIDA isotope scan, ERCP and repeat ultrasound scan. A continued bile leak may be treated conservatively with intraperitoneal drainage of the collection, and stenting of the common bile duct.3

References

-

Pediatric blunt liver injury: Establishment of criteria for appropriate management. Galat JA, Grisoni ER, Gauderer WL. Journal of Paediatric Surgery (1990) 25; 1162-1165.

- Isolated blunt liver trauma: Is nonoperative treatment justified? Amroch D, Schiavon G, Carmignola G, et al. Journal of Paediatric Surgery (1992) 27; 466-468

- Minimally invasive approach to bile duct injury after blunt liver trauma in pediatric patients. Church NG, May G, Sigalet DL. Journal of Paediatric Surgery (2002); 37 ; 773-775

3. Pancreas

Conservative management

With acute resuscitation and pain management.

Routine oral intake is withheld until resolution of symptoms and normalisation of amylase and lipase

Nasogastric drainage with possible NJ feeds or TPN may be required depending on severity.

Where there has been significant trauma a CT scan should be performed to assess the pancrease. Specifically transection of the pancreas should be looked for raising the possibility of duct transection.

If a duct injury is suspected a ERCP can be performed in an older child and possible stenting of the duct considered.

If distal duct has been transected and stenting is not possible then an early distal pancreatectomy should be considered. Conservative treatment can be undertaken but recovery from this injury is slow with associated morbidity.

Note: There is no indication for urgent

laparotomy.

Pancreatic injury

Late problems

Pseudocyst formation.

Symptoms include continued or worsening abdominal pain or increasing nausea and vomiting.

If there is concern then an amylase/lipase along with ultrasound scan should be performed.

Pseudocysts may be treated conservatively though some form of drainage procedure may be necessary if the cyst continues to enlarge.

Drainage usually involves a cystgastrostomy procedure which can be accomplished as an open, laproscopic or radiological procedure depending on expertise.

4. Intestine

- Intestinal injuries are uncommon

- Those that do present are often associated with:

- Rapid deceleration injuries €" causing shear injuries at the DJ flexure, the terminal ileum, caecum or sigmoid colon.

- Abdominal crush injuries "injuries occurring in up to 50% of cases where a lap seat belt is involved.

- Penetrating injury - which may cause damage to more than one loop of bowel.

All these mechanisms of injury demand a high index of suspicion of intestinal injury.

Diagnosis is often delayed.

Plain X-ray or CT scan with presence of free air may suggest intestinal injury, but are not always reliable indicators. Regular clinical evaluation, including auscultation for

bowel sounds, associated with repeat x-rays, may be necessary to

make the diagnosis.

If there is injury to the mesentery and devascularisation of the associated bowel, associated perforation may appear only some days after the original injury.

Evidence of free intra-peritoneal gas is an indication

for urgent laparotomy.

5. Duodenum

Acute duodenal injuries

-

Should be suspected on a history of bruising in the epigastrium, severe epigastric tenderness or bilious vomiting

- Are often associated with pancreatic injuries

- Are particularly associated with bicycle handlebar and seat belt injuries

Injuries may take the form of

-

Intramural haematoma without perforation

- Rupture of the duodenum

Duodenal intramural haematoma can be seen on CT scan, and confirmed - if necessary - on upper GIT contrast study. It may also become apparent if there is ongoing obstruction post-trauma. This can be treated conservatively with nasogastric drainage, but may

take up to 3 weeks to resolve. TPN will be required over this time.

Acute duodenal perforation

-

needs to be a diagnostic consideration at initial presentation

- It can be detected by presence of free air. This air may be retroperitoneal, rather than intra-peritoneal See X-Ray withground glass appearance

- It may also be detected by extravasation of contrast on an upper GI contrast study or CT scan

- Perforation can be delayed if there is an area of devascularisation with the trauma

- Acute perforation is treated with laparotomy

- Late presentations may be managed conservatively with NGT, TPN & antibiotics

Retroperitoneal air seen as ground glass type appearance

6. Kidney

Aspect injury from

-

History

- Wounds

- Bruising in the renal area

- Frank or microscopic haematuria

Investigations

All abdominal trauma patients should have urine analysis done.

Careful monitoring of urine output, with further investigation if microscopic haematuria is seen.

If the patient is relatively well, ultrasound is the simplest way to image the kidney.

However, CT scan with iv contrast is again the investigation of choice, and will give evidence of renal function.2 IVP is irrelevant if a CT scan has been done.

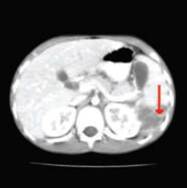

Right renal injury

Management

Most sharp and blunt renal injuries can be treated conservatively.

Antibiotics should be given to patients with renal trauma, and then continued at a prophylactic dose until the injuries have healed.

Indication for laparotomy

On-going blood loss despite resuscitation.

The majority of explorations will lead to a nephrectomy.1

Late problems

Continued haematuria secondary to an AV fistula.

Some of these injuries can be managed by selective radiological embolisation.

Patients with significant injury should be followed up with repeat ultrasound scan and DMSA scan, to assess renal function at 3 months.

Patients with persistent renal damage are at risk of hypertension, and should be followed up for at least 1 year.

References

- Blunt renal trauma in children: experience with conservative management at a paediatric trauma centre. Margenthaler JA. Weber TR. Keller MS. Journal of Trauma-Injury Infection & Critical Care (2002): 52; 928-32,

- Management of kidney injuries in children with blunt abdominal trauma. Wessel LM. Scholz S. Jester I. Arnold R. Lorenz C. Hosie S. Wirth H. Waag KL. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. (2000); 35: 1326-30,

7. Bladder

Suspect injury from

- Patient's history. Bladder injuries typically present after: -Deceleration injury. -Blow to the lower abdomen when the bladder is full.

- Bruising in the suprapubic region.

- Evidence of urine extravasation (oedema of the scrotum, lower abdomen and upper thighs),

- Blood at the external urethra.

- Extraperitoneal extravasation or intraperitoneal rupture.

- Failure to pass any urine.

Management

- Urinalysis,

- Monitoring of urine output

- Ultrasound scan may give clues to the diagnosis.

- CT scan with iv contrast is the investigation of choice.

Laparotomy

- Should be reserved for intraperitoneal rupture.

- If there is any evidence of damage to the bladder neck, insertion of a suprapubic catheter under ultrasound guidance with referral to a paediatric urologist is the safest course.

8. Urethra

Suspect injury

from

- Straddle injury, a fall astride a beam (e.g. the bicycle frame);

- After pelvic fractures.

- Blood at the meatus, or a high riding prostate in older boys, is a classic sign of urethral trauma in boys.

Serious further injury can be caused by inappropriate

attempts at urethral catheterisation

Management

- Investigations include a CT with contrast and an ascending contrast urethrogram.

- If there is evidence of injury, the child should be referred to a paediatric urologist.

- If bladder drainage is needed prior to transfer, a suprapubic catheter should be inserted under general anaesthetic with ultrasound guidance. This is because the bladder anatomy can be seriously distorted by pelvic fractures and extraperitoneal haematoma

Urethreral injury

9. External genitalia

Suspect injury

- External genitalia damage has the same origins as urethral injuries.

- Child abuse should also be kept in mind (see chapter 1.21)

Management

- Lacerations to the perineum can usually be simply stitched in theatre.

- If abuse is considered a possibility, contact the Child

Protection services prior to anaesthetic. This is necessary so that consent is correctly obtained for examination under anaesthetic, and for photographic evidence to be taken in a manner later admissible in court.