Introduction

The linear Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, Exposure (ABCDE) approach to management of severely injured patients in modern, well resourced, emergency departments is increasingly being questioned. A rigid application of the ABCDE principles, where airway is assessed and managed, prior to proceeding to

breathing, which in turn is assessed and managed prior to the C, D and E components, can be inefficient for those patients with multiple complex injuries and competing clinical demands. A contemporary approach recognizes that the management of severely

injured patients often proceeds in a “horizontal” fashion – with a team of skilled individuals addressing multiple tasks at the same time. This approach is thought to be effective in reducing the total resuscitation time1

- and thereby facilitating the early delivery of definitive care. However, this adds complexity to the management of the injured patient as there are multiple processes occurring simultaneously, proceeding at different rates, and occurring in a wide variety

of situations. As a result, the coordination of these processes may be “just as critical for patient survival as making the correct diagnoses or carrying out the most appropriate tasks”2

. This simultaneous management of tasks, personnel and the patient requires both the application of medical expertise and an understanding of human factors. The objective of this chapter is to review some of the human factors that are relevant to reception and resuscitation of a

severely injured child.

Human factors

“Human factors” have been defined as “all the things that make us different from logical, completely predictable machines; how we think and relate to other people, equipment and our environment.”3

One starting point in understanding the relevance of human factors to healthcare provision, is to accept the fact that healthcare is provided by humans. Whilst healthcare providers may be highly skilled, well-motivated, and knowledgeable individuals,

they remain human, and as such are prone to error. Therefore, it is arguable that an understanding of human factors can help mitigate the chances of errors and adverse events.4 Error itself can be viewed from an individual or systems approach. A systems approach

recognizes that given human fallibility, errors will occur even in the best organisation, and therefore risk reduction requires that processes or safeguards be put in place. Reason has described this conception of error as the “Swiss cheese model of system

accidents”5. He argues that systems have multiple layers of defence whose function is to protect errors from occurring. However, each layer, like a slice of Swiss cheese, has weaknesses or holes. The presence of a hole in any single slice does not usually lead to a bad outcome – but where the holes in

multiple layers line up, bad outcomes occur. Reason suggests that holes arise in each layer due to one of two factors – an active

failure – such as a slip, lapse, mistake, or procedural violation, or due to a latent condition – that exists within the system and has arisen from decisions made by “designers, builders, procedure writers and top level management”6

.

Active failures such as lapses and slips are well known to occur more frequently with fatigue, stress, illness, overload, inexperience and complacency. But they are also more likely to be triggered by factors commonly found in complex trauma resuscitations - specifically7

:

- Interruptions and distractions

- Tasks required out of the normal sequence

- Unanticipated new tasks

- Interweaving multiple tasks

However, the specific form of lapse or error is hard to predict, which can hinder attempts to prevent them.

In contrast, latent conditions through the study of systems, can be identified, and ideally, remedied before an adverse event occurs.

Non-technical skills

Non-technical skills commonly refer to those human factors that operate at the individual level. They include interpersonal skills – such as leadership, team work and conflict management - as well as cognitive skills such as situational awareness, planning and decision

making. Communication is a core component that runs through all of these non-technical skills. These skills are part of an understanding of how human factors affect performance during critical events.

Leadership

Leadership has been described as a “multi-dimensional, complex behavior that includes effective communication, efficiency, decision-making, and resource management skills.8

” It is regarded as an essential non-technical skill, required for the optimal functioning of the trauma team.9

The clear identification of a team leader leads to increased adherence to trauma guidelines, a more complete secondary survey, and improved trauma team coordination10

. The goal of the team leader is to ensure timely appropriate care to the patient, and facilitate rapid delivery of definitive therapy. In order to do this they need to accept responsibility for the patient, provide strategic direction based on the anticipated needs of the patient and monitor the progression of

the clinical care provided. They may need to provide feedback or teaching for other team members, as well as coordinate the needs and preferences of multiple specialist teams. The attributes needed for leadership have been summarised as follows11:

- An effective leader should know the names and capabilities of each of his/her team members. Simply knowing the name of team members has been shown to increase motivation and allocation of tasks commensurate with the skill level of the individual increases efficiency and

performance.

- A leader should accept the leadership role – as the person best placed to maintain situational awareness, the team leader should be accepting of their responsibility as leader. The role should be allocated to a senior clinician who has credibility with his/her

team.

- A leader should be able to stay calm – and maintain focus within their team

- A leader should be a good communicator – this requires both an ability to listen, and an ability to make and convey decisions to the team. A leader should be prepared to manage conflict.

- A leader should delegate tasks appropriately, maintaining an awareness that no single team member is overburdened with tasks, as well as ensuring no member is struggling to perform a required task. A leader should be aware that the stress inherent in the situation may lead to a

team member performing at a lower level than they normally would.

- A leader needs to at times be assertive and authoritative in order to drive patient management. It is thought that directive leadership is more effective where patients are more severely injured and when teams are less experienced.12

- A leader needs to maintain situational awareness – this is the ability to constantly monitor the situation, listen, and decide on a course of action.

- A leader should also involve the team in decision making, update them on the overview of the patient, and utilize their knowledge and experience.

Consideration and application of these attributes can help individuals refine and develop their leadership skills. And, although it is difficult to measure precisely, training has also been shown to increase leadership skills.

Teamwork

The trauma team that assembles and cares for the severely injured child is not simply a group of people working side by side. Rather they are bound together, as a team, by their single purpose in achieving the best outcome for their patient. As members of a team they have

specific roles or functions to perform and interact with each other “dynamically, interdependently, and adaptively.13

” This means they are not just performing task roles (jobs team members do) but they are also performing team roles (working, supporting and looking out for each other)14

. Furthermore, team members are not mere subordinates following the direction of a team leader. Rather they must demonstrate good “followership” or “teamwork” which involves them actively engaging in patient care and utilising their own expertise, knowledge, and clinical skills to help

the team achieve its goals. This may involve them challenging the team leader, in an appropriate fashion, when required based on their own assessment the patient. It may involve ensuring that the information they need to relay to the team leader is done so at the appropriate time - when

team leader is ready to receive it. Important information will not be heard or interpreted if delivered in the wrong way at the wrong time:15

team members need to gauge the optimal time at which they should relay information back to the team leader – doing so requires a degree of awareness of the overall priorities for the patient and an ability to assess the relative importance of the information they themselves wish to relay. Furthermore, followership may involve

structuring questions/requests in a way that is helpful to the team leader. For example, where nursing staff have access to a drug book or other resource, they may find the question: “Are you happy with a 0.5mg/kg dose of ketamine for this patient? It works out to be 20mg, based

on an estimated weight of 40kg,” is superior to “How much ketamine do you want?” The latter question places a greater cognitive load on the team leader – it requires them to recall an appropriate dose of a drug and then to perform mental arithmetic when this information

is typically readily available to team member who posed the question. The former question demonstrates an ability to anticipate the needs of the team leader and the patient. The relevant information is presented to the team leader and this allows them to devote a greater amount of their cognitive

resources on deciding if this is the right drug at the right dose at the right time for the patient – without also having to contend with mental arithmetic.

The attributes necessary for good followership (or teamwork) have been summarized as follows16

:

- Team members should clearly communicate clinical findings and actions taken.

- Team members should anticipate the needs of others and adjust to each other’s actions as well as the dynamic needs of the patient.

- Team members should be prepared to raise concerns about clinical or safety issues as well as feel empowered to speak up in the presence of errors (their own and if they observe those of others). They should be assertive enough to encourage debate, or draw attention to a problem,

but they should not be destructive.

- Team members should help the team leader by listening carefully to briefing and instructions and communicating as necessary for good teamwork.

- Team members should support and show respect for other team members and show tolerance towards hesitancy or nervousness, facilitating a safe environment for them to speak up.

- Team members should cross-monitor their teammates’ performance to aid with anticipation the needs of the patient and their team members as well as to assist with workload distribution.

- Team members should perform skills to the best of their ability, sharing their workload fairly and appropriately.

- Team members should admit when they cannot do something and need help.

- Team members should have a shared understanding of accepted procedures and policies at their institution and knowledge of how events should proceed.

- Team members should practice scenarios to facilitate good team work and identify latent conditions for error / system failure.

- Team members should debrief, quickly after events and in more depth later.

Conflict management

Conflict is inevitable in almost every team, and its successful resolution is required for optimal team performance. Conflict is likely to arise in trauma teams for a number of reasons17:

- Tensions occur between individuals and the team as a whole in terms of goals, agenda and the need to establish an identity

- For optimal performance the leader has to foster both support and confrontation among team members – if members fail to challenge each other appropriately, there is a risk of a poor outcome

- Daily activities must balance against performance in the moment and the need to enhance team learning

- The team leader needs to find a balance between managerial authority and individual team member autonomy.

The potential for conflict is further increased by the need to make decisions in situations with incomplete or potentially conflicting data. Individuals within teams will bring with them their own set of experiences and motivations which lead to divergent

perspectives and opinions. This range of opinions can be seen as constructive, as when correctly managed, they can help a team arrive at a more comprehensive assessment of the patient than any single assessor is able to obtain.

However, conflict that spills into the territory of a power struggle, where the focus becomes “who is right” rather than “what is right” can be destructive18

. The costs of conflict within teams include the wasting of both time and resources and distraction away from the management of the patient. Conflict within the team ought to be addressed by the team leader. Whilst several models exist on how to do this, the following principles

underlie mos19

:

- Conflict is extremely likely if not inevitable due to the differences in perspective and opinion that individuals will bring to the team.

- Avoidance of the conflict may lead to an inferior outcome for the patient than active engagement and resolution of the conflict.

- People must be motivated to address and resolve conflict.

- Resolution of conflict requires behavioural, cognitive and emotion skills – which can be acquired.

- Emotional skills require self-awareness.

- The environment must be neutral and feel safe.

Ultimately however, most defer final responsibility for the course of action taken to the team leader, who in extreme situations may ask disruptive team members to leave the resuscitation.

Situational Awareness

Situational Awareness is a key component of effective trauma team management. It has been described as “knowing what is going on so you can figure out what to do.”20

It requires a global overview of the patient – knowledge of what has happened to the patient, their current state and what is likely to happen to the patient. Situational awareness is informed by an understanding of how mechanism influences injuries, the patients past medical history, detection of abnormal

clinical and vital signs, an ability to discern relevant clues and set aside distracting information, and expertise in being able to predict diagnoses based on incomplete information in dynamic situations. A designated trauma team leader should remain

“hands-off” in a complex trauma in order to retain overall situational awareness. A successful team requires the trauma team leader to periodically share situational awareness with them – most commonly via a “sit-rep”, “recap” or summary of the patient’s current situation

with a recommendation for the ongoing course of action.

Planning and Decision Making

All healthcare professionals wish to make “good” decisions during critical situations. Such decisions are characterized by the following21:

- They promote safe, efficient and effective task management.

- They consider the current situation in the context of time limitations and resource availability.

- They are commensurate with human factors – in that they account for limited information processing capacity, the influence of motivation and emotion on behaviour, the limits of mental and physical workload, and the variable response / resistance of individuals to stress.

- They lead to a timely and appropriate course of action.

- They anticipate complications of treatment or diagnostic interventions.

A key attribute in good decision making is the ability to predict what might happen to a patient with a particular set of injuries were differing courses of action to be taken, and then selecting the most appropriate course of action and communicating it to the team. Many such

decisions may be reviewed and contemplated through a process of mental simulation prior to the arrival of the patient. Team leaders are encouraged to pre-brief their teams where there is time to provide this shared mental model with their team. A variety of situations may be presented to

the team with appropriate courses of action suggested for each one. In doing this the team leader is psychologically preparing his team and facilitating their own decision making process by outlining an anticipated structure for the course of the resuscitation. Clearly, an adaptive model is required should

the patient arrive in a situation that is different to that predicted, but where the prior mental model and the observed reality are well matched, the team leader will have reduced their own cognitive load during the resuscitation.

Pre-arrival synthesis

One method of making a plan and facilitating decision making is to use an explicit structure during a pre-arrival briefing to enable a shared mental model to be held by all the team members. The current model taught at the Royal Children’s Hospital is for the team leader to

include a “synthesis” within the pre-arrival briefing that augments the information provided in the pre-arrival notification. This synthesis [xxii] has five components:

- Severity of injuries

- Mechanism of injury (with comment on whether blunt or penetrating injury)

- Level of concern

- Predicted injuries

- Treatment priorities

Severity

Commenting on the severity at the start allows the team to begin visualising whether this will be a standard resuscitation, or whether the patient will be in extremis and require a more urgent approach. If all team members are anticipating the same degree of illness/injury they are more likely to then

enter the case in an appropriate and co-ordinated fashion.

Mechanism of injury

Stating the main type of injuring force can prepare the team for certain types or patterns of injury. Blunt trauma often results in injuries to multiple body areas, internal bleeding and internal organ lacerations/contusions. Penetrating trauma may be more likely to result in external bleeding and

more direct/localised areas of injury. Extremity crush injuries or amputations may be more likely to result in external bleeding and potentially metabolic complications.

Certain mechanisms may also trigger specific concerns. For example, high risk features of motor vehicle accidents - such as high speed, rollover or ejection warrant a more thorough search for occult serious injury even if the patient does not appear seriously injured on initial assessment. A penetrating injury (such as a stabbing) to

the chest may trigger the team to consider tension pneumothorax, haemothorax and cardiac tamponade. It may also prompt the team to consider looking for additional wounds in the “hidden” areas for stab injuries (such as axillae, groins / perineum, buttocks).

These are obviously generalisations but focusing the team on the type of injury force and expected injuries can allow them start visualising what the case may entail and potential injury patterns they can expect. Furthermore, stating the problem out loud may help the team leader

identify potential management priorities to conduct on arrival of the patient.

Example: “We are

expecting a moderately unwell, blunt trauma patient, pedestrian vs car. The

ambulance service have identified a head injury and a lower limb injury. From

the mechanism we should also retain a high index of suspicion for an abdominal

or pelvic injury as these are common with this type of mechanism. Let’s make sure a pelvic binder if available

to place on the patient, if they don’t already have one on.”

Level of concern

It is important for the team leader to convey their level of concern to the team prior to patient arrival to ensure that everyone understands the degree of confidence the team leader has to manage the case, any assistance they may require and the urgency/efficiency

the team leader will expect of them. By giving this part of the synthesis an emotional context and eliciting concern in the team, the team leader may rapidly motivate his team into action, as well as elicit a stronger sense of followership within the team, than merely stating

facts is able to do.

It also allows the team leader to express any uncertainties or specific difficulties they themselves are expecting, which may relate to the specific predicted injuries and their experience in managing them, their confidence in managing a large team, or

other issues they may have that may impact their ability to manage the case.

Example: “My

level of concern for this case is high. We

know there is head injury which will require a prompt CT scan to identify the

nature of this injury. However, whilst

the vital signs are only slightly abnormal at the moment, I’m concerned about

the potential for rapid deterioration due to abdominal or pelvic bleeding. If this occurs we may need to prioritise

theatre for haemorrhage control over a CT head.

Suspected injuries

Rather than simply stating the body region that is injured (and assuming the team knows the potential specific injuries that may occur in that region), it is more useful for the team leader to specifically name the life threats they anticipate the patient may have

based on the information provided from the pre-hospital providers and the clinical signs that have been relayed.

For example, in blunt trauma:

| Instead of saying “the patient has a ...” |

Say “I’m concerned the patient may have….” |

| Head injury |

Intracranial bleeding |

| Chest injury |

Haemo/pneumothorax, flail chest, lung contusion, aortic injury |

| Abdominal injury |

Solid organ injury leading to intra-abdominal bleeding |

| Pelvic injury |

Pelvic fracture leading to massive haemorrhage |

|

Limb injuries:

Crush injury

Amputation |

Potential open fractures & haemorrhage

Amputation leading to massive haemorrhage |

This step removes the assumption that team members know the specific injuries that may occur in different body regions and allows them to instead start preparing for specific treatments that may be needed. Using the specific life threat also helps “prime” the team members, enabling the ability to anticipate

patient requirements, and facilitate their shared mental model of the situation.

Treatment priorities

Whilst the team will perform a standard primary survey, certain issues may be more urgent and require re-sequencing of the assessment and management steps. For example, in a patient with a tension pneumothorax, the team leader may direct the procedure doctor not to perform IV

access first, but rather perform chest decompression as a priority.

In the case above, treatment priorities may be:

“When the patient arrives, the priority will

be to assess his haemodynamics and make a quick decision about whether he needs

blood, or bilateral finger thoracostomies and chest drain insertion. I’d also like rapid chest and pelvic films so

we can quickly rule out major injuries in those areas and then focus on the

head and abdomen”.

Case summary (“recaps”)

This system can also be used to synthesise and summarise a trauma case during the resuscitation, simply by substituting “suspected injuries” with “injuries found”. It has been suggested that in addition to the initial debrief a “recap” or “sit-rep” of the patients status is utilised

following a major intervention, and at 20mins into the resuscitation. Doing so realigns the shared mental model of the team, giving them an increased situational awareness, and knowledge of the patient’s current priorities.

For example:

OK team, can I please have everyone’s

attention. This patient is a severely injured having presented in haemorrhagic

shock after being struck at speed by a car. The injuries we’ve found so far are a blunt abdominal

injury with peritonism and likely intra-abdominal bleeding, possibly from liver

or splenic laceration. His pelvis is clinically

stable. His haemorrhagic shock has responded to 1 unit of packed red blood

cells. He also has a mild closed head injury with a GCS of 13. He doesn’t need intubation right now , and I think

he’s stable enough to get to CT, so the priorities now are to hang a 2nd

unit of packed cells and commence this only if the BP drops to below 100mmHg, again. I’ve notified CT that we’ll be there in 5

minutes so if the circulation nurse could ensure we are attached to the

transport monitor and the transport bag is ready as soon as possible. Finally, could the surgical registrar please contact

theatre and make sure there is an available theatre, should CT indicate he

needs immediate surgery.”

Communication

Good communication is critical to all the non-technical skills discussed above. Without it, leadership, followership, conflict resolution, planning and decision making are all severely constrained. Understanding how error can arise through dysfunction communication requires some thought about what communication

usually entails. It is a mistake to think that communication is simply limited to the specific words used to convey information from one person to another. The “square model” of communication has been used to identify how any message can have four aspects (like the four sides of a square)23

. This model postulates that any message contains information about:

- the content of the message – that is information about facts, objects or event.

- the speaker – that is it contains a self-revelatory component

- the relationship between the speaker and the intended recipient of the message

- an appeal to act – that is every message contains an implicit direction to the recipient

Which aspect of the message is most important is open to interpretation by the recipient of the message. The speaker may have surprisingly little ability to influence or even predict how the recipient will interpret the message, so what is heard may not be what is intended.

So for example, when a circulation nurse says: “The blood pressure is 86 / 50” – in addition to stating the actual blood pressure (the content), they may also reveal their concern about a hypotensive patient who is deteriorating (a self-revelation);

a lack of confidence in the team leader who hasn’t yet noticed the downward trend of the patient’s blood pressure (the relationship component) and an implicit suggestion to give blood to a patient with haemorrhagic shock (the appeal component). The speaker may

intend to appeal for action in this case, but the listener may interpret the statement as an effort to undermine their authority by suggesting they have failed to notice the change in the patient’s condition.

Given the multitude of aspects of both giving and receiving information, teams adopt specific techniques to minimize misunderstanding. Communication should be:

Correct communication

Correct communication involves the message transmitted being the correct one. So for the circulation nurse in the above example who wants to convey an appeal for action through their statement: “The blood pressure is 86/50” may be better served by stating “The patient remains hypotensive, shall we administer blood?”

In order to do this, team members need to have a degree of metacognition in knowing what they are hoping to be understood.

Correct communication also includes ensuring that what is said is heard and understood. A method for minimizing error here, is the use of closed loop communication. This is a 3-step process, where the speaker:

- issues a direction,

- which is then “read-back” by the recipient,

- the “read-back” is then confirmed by the original speaker.

The recipient will also confirm when the order is completed. For example,

- the team leader may say “James, please give 50mcg of fentanyl intra-nasally”,

- James responds by saying “You want me to give 50mcg of fentanyl IN”,

- To which the team leader then confirms – “Correct, 50mcg of IN fentanyl”.

- Once the medication has been given, James ought to call out “50mcg IN fentanyl given.

Clear communication

Clear communication requires an avoidance of ambiguous or mitigating language. It is directed towards a specific person so the team knows to whom the message is directed. Examples include:

- “James, please draw up 50 micrograms of fentanyl” rather than “can someone draw up some analgesia?”

- “Is someone happy to put in the chest drain ?” rather than “Belinda please place the chest drain on the right side”

Concise communication

Concise communication involves being brief and to the point – stating problems as simply as possible. Examples include:

- “There are weak radial pulses present bilaterally”

- “I’m unable to get an IV – is there anyone else who can help, or shall I place an IO”

Trauma reception and resuscitation

The management of severely injured patients in Emergency Departments can be thought to consist of 3 phases of care:

- A pre-arrival phase

- A reception and resuscitation phase

- Disposition to the ward / intensive care or theatre

It is worth considering the impact of human factors at each of these stages of the patient journey

Pre-arrival phase

In mature trauma systems, the arrival of a severely injured patient to hospital is often heralded by a notification from the pre-hospital services. This typically allows for at least 10 minutes of time during which a team can be assembled and preparations made for the

patient about to arrive. A large number of decisions are made in this phase even though the information available to make such decisions may be incomplete and open to various forms of interpretation. At RCH there are a number of systems based measures that aim to reduce error. These include the following policies:

- Standardised criteria for Trauma Team Activation

- Use of a Trauma Pre-arrival Checklist

- Defined default role allocations and role responsibilities

Trauma Team Activation

There are four criteria used at RCH, any one of which is sufficient to

activate the Trauma Team. Unlike many adult trauma team activation criteria, RCH does not use a mechanism criteria. The four criteria that can be used to activate the Trauma Team are:

1. Abnormal physiological parameters or a GCS

<9

2. Specific anatomical injuries. These include:

- Spinal cord injury

- Flail chest

- Major vascular injury

- Penetrating injury to head or torso

- Crush injury to head or torso

- Severe blunt injury to head or torso

- Limb amputation

- Burns >20% BSA or inhalation injury

- Significant injury to multiple body regions

3. Multiple patients: when 3 or more trauma patients are expected

4. At the request of the trauma Team Leader

Trauma team activation requires the attendance of ED and PICU medical and nursing staff, the paediatric surgical registrar, an anaesthetist, a radiographer, an ED social worker and Emergency PSA, to the resus area of the Emergency Department 10 minutes prior

to the estimated arrival of the patient.

Pre-arrival Briefing

Once the trauma team has been activated, and its members gathered together, the Trauma Team Leader is tasked with providing a succinct synthesis (detailed above) and then allocating roles and tasks to team members. A primary plan based on the anticipated course

of the patient is discussed with variations should specific criteria be met. Typically team members will have tasks allocated to them that reflect the anticipated needs of the patient arriving. Given the large number of people and tasks involved, errors of omission can occur at this time. Attempts are made to mitigate this risk

through the use of a checklist which lists many of tasks that need to be allocated out to the team.

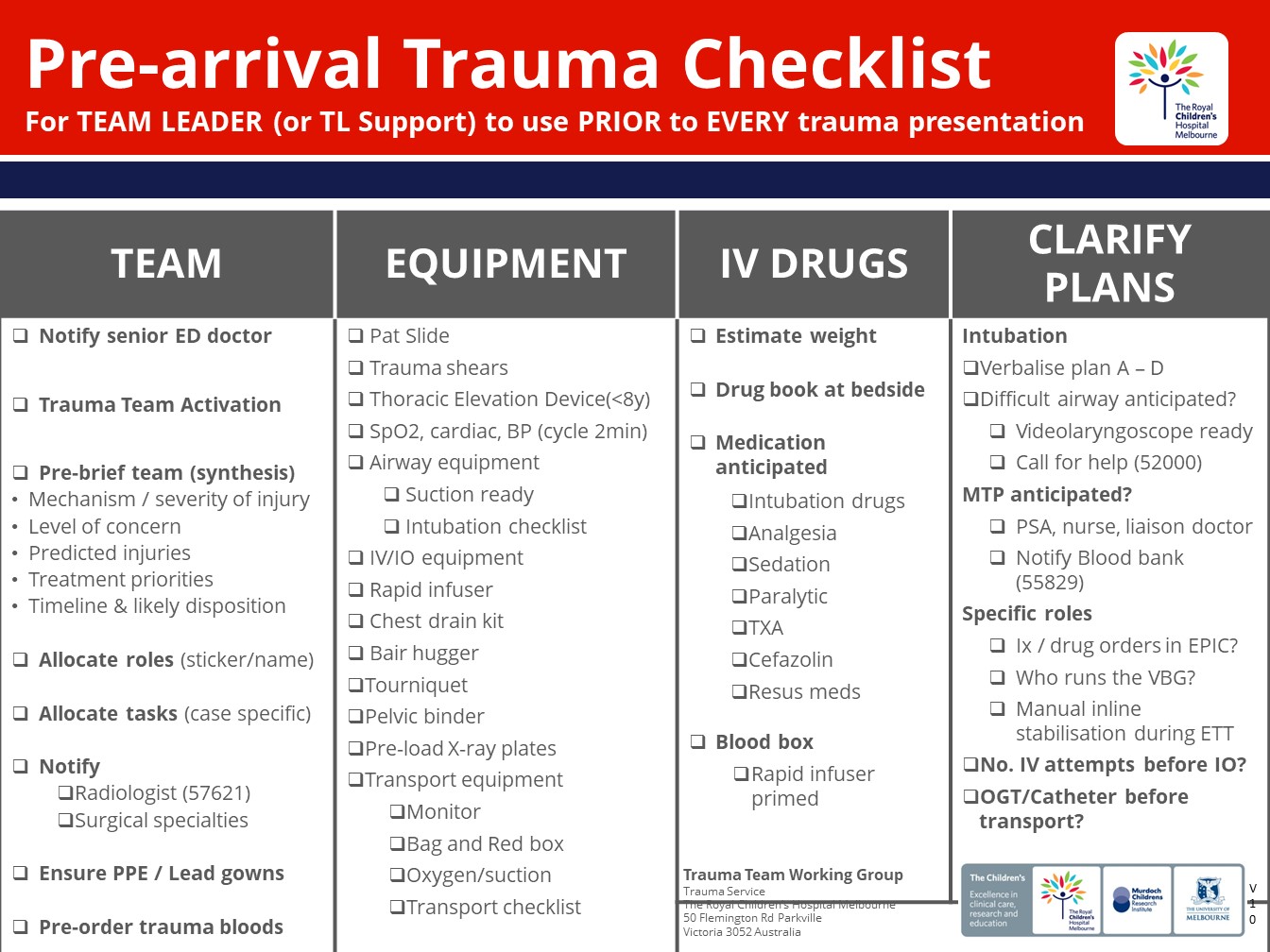

Pre-arrival Trauma Checklist v11

The RCH Pre-arrival Trauma checklist prompts the trauma team leader to allocate tasks related to:

- Organisation of the trauma team – e.g.: sharing the mental model with a synthesis, allocating roles, ensuring PPE and lead gowns are worn, and calling for help from specialties not automatically notified through trauma team activation.

- Preparation for patient specific issues – e.g.: estimating weight, utilization of a thoracic elevation device if under 8

- Preparation of medication and monitoring

- Preparation of other equipment

In-house simulation training at RCH has shown that where the Pre-arrival Trauma Checklist is not used, errors of omission are more common.

Some of the cognitive load of role associated with task allocation to a group whose capability may be somewhat unknown to the team leader is mitigated against by establishing default roles and tasks based on specialty. These are identified in the RCH Roles and

Responsibilities Policy and further discussed in the subsequent chapter.

Reception and Resuscitation

Handover

Once the patient arrives the team leader and senior paramedic should rapidly agree if handover should take place prior to patient transfer onto the ED trolley – this involves a 5 second evaluation for the presence of a life threat.

In the absence of an immediate life threat, a rapid "I-MIST-AMBO" handover (see below) should occur with the patient on the ambulance stretcher.

| I |

Identification |

Identification of clinician, then identification of patient with name, age and weight if known |

| M |

Mechanism |

Immediate events leading to injury |

| I |

Injures |

Injuries detected |

| S |

Signs |

Vital signs – include initial set, the worst set (especially in neurotrauma) and most recent set of vitals |

| T |

Treatment |

Procedures undertaken, medications given, and an indication of effectiveness of each intervention |

| A |

Allergies |

To what and level of severity if known |

| M |

Medications |

Regular medications taken by pt |

| B |

Background |

Past medical history

Any advance care directives |

| O |

Other |

Relevant social information

Family awareness / contact

Handover of documentation |

- Handover should be a "hands-off" time for the hospital staff. The aim of having a handover prior to patient transfer is to ensure all team members are able to hear a succinct handover - it has been suggested that an effective handover should last 60-90

seconds.

- Increased use of the IMIST-AMBO handover has been shown to increase the volume of information given during the handover, and lead to fewer questions / interruptions of the handover by ED staff, reduce the total handover duration, and reduce the number of repetitions

by both paramedics and ED clinicians – suggesting greater recipient comprehension and retention 24

.

- This does not preclude a further more detailed handover taking place between the Team Leader and the paramedic / transfer team once transfer of the patient has occurred to the ED trolley, and the primary survey commenced.

- The haemodynamically unstable patient, or the patient that requires life-saving intervention on arrival, should be transferred to the ED trolley immediately, and the primary survey commenced. Handover will be directed to the Team Leader and Scribe whilst the rest of the trauma team

assesses and manages the patient.

Primary survey

The function of the primary survey is to simultaneously assess and manage life threats. It is a crucial data gathering phase that allows good decision making to occur. Failure to complete the primary survey can lead to life threats being missed, and an inability to make good decisions about how to care for the

patient.

Environmental factors – such as noise, overcrowding and disorganisation – need to be considered in the management of the primary survey. Noise in particular can rapidly escalate. Louder rooms can lead to louder voices trying to be heard. The risk of this is that information gets

missed and requests from the team leader go unheard and further dysfunction ensues. Exposure to loud noise may detrimentally affect short term memory and impair auditory vigilance (for example being able to detect alarms). Management of the noisy environment can be managed through preventing

overcrowding and specifically asking the team to observe the “sterile cockpit” rule – where all unnecessary conversation stops - for high risk moments (for example induction and intubation).

Disorganisation can be mitigated through ensuring team members are aware of where the equipment they require to perform tasks prior to the patient arriving. It has been suggested that allocating a role of logistics and safety to a team member would reduce disorganisation – this person would be tasks with

crowd and noise control, optimising patient positioning, layout of equipment and safe movement of clinical personnel within the resuscitation, as well as ensuring that checklists prior to high risk tasks are reviewed.25

One latent threat identified through the RCH Trauma Team Training program relates to role allocation during the primary survey. Where a surgical registrar has been allocated to the assessment role, and is then required to switch roles to perform a procedure – such as a chest drain insertion – the

primary survey may fail to be completed and other life threats fail to be detected.

Documentation of the primary survey is ideally done in a contemporaneous fashion. This role is typically allocated to the doctor in the Team Leader Support role at RCH. The expectation is that this doctor utilises the Trauma Tab in the electronic medical record to act as an aide-memoire in ensuring all important steps

of the primary survey have been carried out and documented.

At the end of the primary survey, the team leader should recap and summarise what progress the patient has made and the immediate plan. A “command huddle” may be utilised to allow senior decision makers (typically ED team leader, surgical consultant/registrar and anaesthetist) to plan the disposition

of the patient. A plan for CT imaging / OT or admission to PICU / the ward should be confirmed and communication with those departments delegated to appropriate team members. This command huddle should typically occur within 20-30minutes of patient arrival to the emergency department.

In most cases, the secondary survey should be commenced (and completed) in ED – however, there are some occasions where the primary survey identifies life threats that cannot be managed in the ED – massive intracavitational bleeding. In these cases the patient may need their ongoing resuscitation to be

managed in theatre as part of the primary survey intervention. The secondary survey will need to be completed either concurrently or following surgical intervention.

-

Driscoll, PA, Vincent CA. (1992) Organizing an efficient trauma team. Injury 23:107-110

- Fitzgerald, MC et al (2006) Trauma Reception and Resuscitation. ANZ J. Surg 76:725-728

-

The ‘Clinical Human Factors Group’ as cited by Norris, EM & Lockey AS (2012) Human factors in resuscitation teaching. Resuscitation

83:423-427

-

Mercer, S. et al (2014) Human factors in complex trauma. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia, Critical Care & Pain

15(5):231-236

-

Reason, J (2000) Human error: models and management. BMJ 320:768-70

-

Reason, J (2000) Human error: models and management. BMJ 320:768-70

-

Bleetman, A. et al (2012) Human factors and error prevention in emergency medicine. Emerg med J 29:389-393

-

Ford et al. (2016) Leadership and Teamwork in Trauma and Resuscitation. Western Journal

of Emergency Medicine 17(5):549-556

-

>Hjortdahl, M et al (2009) Leadership is the essential non-technical skill in the trauma team – results of a qualitative study. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine

17:48

-

Barach, P., & Weinger, MB (2004) Trauma Team Performance, in Wilson, W., Grande, C., & Hoyt, D., (eds) Trauma;Resuscitation,

Anesthesia, Surgery & Critical Care New York, Dekker

-

Adapted from Norris, EM & Lockey AS. (2012) Human factors in resuscitation training, Resuscitation 83:423-427

-

Ford et al. (2016) Leadership and Teamwork in Trauma and Resuscitation. Western Journal

of Emergency Medicine 17(5):549-556

-

Norris, EM & Lockey AS. (2012) Human factors in resuscitation training, Resuscitation 83:423-427

-

Norris, EM & Lockey AS. (2012) Human factors in resuscitation training, Resuscitation 83:423-427

-

Mercer, S. et al (2014) Human factors in complex trauma. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia, Critical Care & Pain

15(5):231-236

-

Adapted from Norris, EM & Lockey AS. (2012) Human factors in resuscitation training, Resuscitation 83:423-427and from Barach, P., & Weinger, MB (2004) Trauma Team Performance, in Wilson, W., Grande, C., & Hoyt, D., (eds) Trauma;Resuscitation, Anesthesia, Surgery & Critical Care New

York, Dekker

-

Barach, P., & Weinger, MB (2004) Trauma Team Performance, in Wilson, W., Grande, C., & Hoyt, D., (eds) Trauma;Resuscitation,

Anesthesia, Surgery & Critical Care New York, Dekker

-

St.Pierre, M., Hofinger, G., & Simon, R. (2016) Crisis Management in Acute Care Settings: Human Factors and Team Psychology in a High-Stakes Environment (3rd ed). Springer – available as an ebook via :

www.springer.com– accessed 1st June 2018.

-

Adapted from Overton, AR., & Lowry, AC (2013) Conflict Management: Difficult Conversations with Difficult People Clin Colon Rectal Surg 26(4):259-264

-

Adam, EC (1993) Fighter cockpits of the future Digital

Avionics Systems Conference 12th DASC., AiAA/IEEE as quoted by St.Pierre, M., Hofinger, G., & Simon, R. (2016) Crisis Management in Acute Care Settings: Human Factors and Team Psychology in a High-Stakes Environment (3rd ed). Springer –

available as an ebook via :

www.springer.com– accessed 1st June 2018.

-

Adapted from St.Pierre, M., Hofinger, G., & Simon, R. (2016) Crisis Management in Acute Care Settings: Human Factors and Team Psychology in a High-Stakes Environment (3rd ed). Springer – available as an ebook via :

www.springer.com– accessed 1st June 2018

-

Based on system as taught on the Emergency Trauma Management (ETM) Course

-

As reported in St.Pierre, M., Hofinger, G., & Simon, R. (2016) Crisis Management in Acute Care Settings: Human Factors and Team Psychology in a High-Stakes Environment (3rd ed). Springer – available as an ebook via :

www.springer.com– accessed 1st June 2018.

-

Iedema, R. et al. Design and trail of a new ambulance-to-emergency department handover protocol: ‘IMIST-AMBO’

-

Hicks, C & Retrosoniak, A (2018) The Human Factor – Optimizing Trauma Team Performance in Dynamic Clinical Environments Emerg Med Clin N Am 36: 1-17