Introduction

Chylothorax is characterised by the accumulation of chyle, a lipid and protein rich fluid within the pleural space. It often occurs due to thoracic duct trauma which can be caused by increased intrathoracic pressures. On Rosella and Koala wards, this

postoperative complication may be seen post-cardiac surgery in patients with intrathoracic drains insitu.

Chylothorax is often characterised by a change in drainage appearance (from haemoserous to a thick, opaque and yellow texture), an increase in drainage output (particularly with the consumption of fatty foods), an increase in triglyceride levels and elevated

respirations with more laboured work of breathing. Chylothorax may also be associated with tumours (lymphoma, teratomas or Wilms), chest trauma, congenital chylothorax, congenital lymphatic malformations and syndromes (such as Down Syndrome or Noonan

Syndrome).

Aim

To guide the detection of chylothorax as well as promote its management in a safe and effective manner amongst nursing and medical staff.

Definition of Terms

- Chyle:

During the digestion of fatty foods, fat is broken down into chyle within the small intestine. Chyle is then taken up by lymphatic vessels and collected in the thoracic duct before draining into the blood stream. It is a lipid and protein rich fluid.

It has a milky appearance and also contains albumin, lymph, emulsified fats, lymphocytes, enzymes, immunoglobulins and fat-soluble vitamins.

- Chylothorax: Chylothorax is characterised by the accumulation of chyle in the pleural space. The lymphatic vessels are in close proximity to blood vessels, therefore chyle can leak into the pleural space if the lymphatic vessels are compromised

either from damage during cardiothoracic surgery, infiltration from disease or tumours and if they are put under high pressure.

- Medium Chain Triglyceride (MCT) Diet: A diet very low in long chain fats and supplemented with Medium Chain Triglyceride (MCT) diet. MCTs are directly absorbed into the portal circulation bypassing the lymphatic system. MCTs are essential for

ensuring adequate energy intake in this highly restricted diet.

- Monogen: A nutritionally complete, low fat and powdered feed containing whey protein. This formula is low in long chain triglycerides and high in medium chain triglycerides.

- Parental Nutrition (PN): is a sterile IV solution of protein, dextrose, electrolytes, vitamins, trace elements and water (nutrient) given together with a fat emulsion (lipid).

- Somatostatin: an endogenous hormone that acts on the gastrointestinal tract.

- Thoracic

Duct: One of the primary ducts of the lymphatic system which recirculates lymph into the bloodstream.

- Thoracic

Duct Ligation: a surgical procedure performed to repair the thoracic duct leak if it fails to repair itself post conservative treatment and parenteral nutrition.

Complications Associated with Chylothorax

Ongoing losses of chyle can result in:

- Increased risk of infection

- Malnutrition

- Hypoalbuminaemia (low protein level in the blood)

- Increased mortality

- Immunosuppression

- Respiratory compromise

- Longer postoperative recovery

- Prolonged ventilator dependence

Diagnosis and Assessment

A chest drain (either underwater seal drain or redivac) will be inserted into the pleural space. The pleural fluid drained will be assessed for chyle using the following indicators:

- Appearance: Chylothorax is most commonly detected by its thick, creamy like appearance in the chest drains of enterally fed patients as opposed to haemoserous pleural drainage.

- Drainage: Sudden increase in the amount of drainage from drains, particularly in conjunction with the consumption of fatty foods, or persistent chest drainage ( >5mls/kg/day) after 4 post-operative days irrespective of appearance

- Please note for children with very high output chylothorax (>100mls/kg/day), these children are usually managed in PICU.

- Imaging: A chest x-ray and chest ultrasound are used to confirm pleural fluid as well as show the location of and measure the size of the effusion.

- Drain

specimen: Chylothorax is characterised by an increase in white cell count (WCC) and triglyceride levels when a drain specimen in taken.

- Clinical

symptoms: Some patients can be asymptomatic while other patients can present with shortness of breath, increased work of breathing, cough and overtime time, chest discomfort can develop.

Figure 1: Assessment and Detection of Chylothorax

Management

Treatment is comprised of conservative and invasive interventions as listed below:

Conservative Treatment: is the primary and first line of treatment utilised. It is comprised of dietary modifications which include monogen feeds for infants and low fat / MCT diet for children and adolescents. Conservative treatment also includes

the cessation of fatty food consumption. This form of treatment aims to slow down the production of chyle, therefore allowing the thoracic duct to repair itself.

Invasive

treatment: If conservative treatment fails to resolve the chylothorax (i.e., reduce drainage, resolve drainage colour and correct bloods), invasive treatments are implemented.

- The first line of invasive treatment is Parental Nutrition (PN) and lipids which are administered via a central line. The patient is to remain nil by mouth whilst receiving PN. If PN fails to resolve the chylothorax, the last resort is surgical repair

of the chylothorax. This includes a ligation of the thoracic duct (to repair the leak) and or surgical drainage of the pleural effusion.

Assessment and Management

Patient Assessment

Regularly monitor and document observations as per the RCH Nursing Guideline: Observation

and Continuous Monitoring.

Vital signs

- Auscultate chest at shift commencement

- Routine four hourly observations including assessment of respiratory effort

- If the patient is on an opioid infusion continuous monitoring is required and hourly cardiorespiratory observations (HR, SpO2, BP, RR) should be documented

For ward areas

- On insertion of chest drain monitor and document on EMR flowsheets patient observations (HR, SpO2, BP, RR, respiratory effort and temperature):

- 15 minutely for 1 hour

- 1 hourly for 4 hours then 1-4 hourly as indicated by patient condition

In conjunction with both conservative and invasive treatments, the following are to be adhered to:

- Daily weights and weekly heights

- Continue dietician involvement

- Monitor diet and avoidance of fatty foods

- Strict fluid balance

- Hourly drain output measurements and drainage appearance documentation

- Consider replacement of drainage losses and fluid restrictions in collaboration with medical teams (decided on a case-by-case basis)

- Monitor for signs of infection

Refer to RCH Nursing Guideline: Chest

Drain Management for more information regarding the management of Chest Drains.

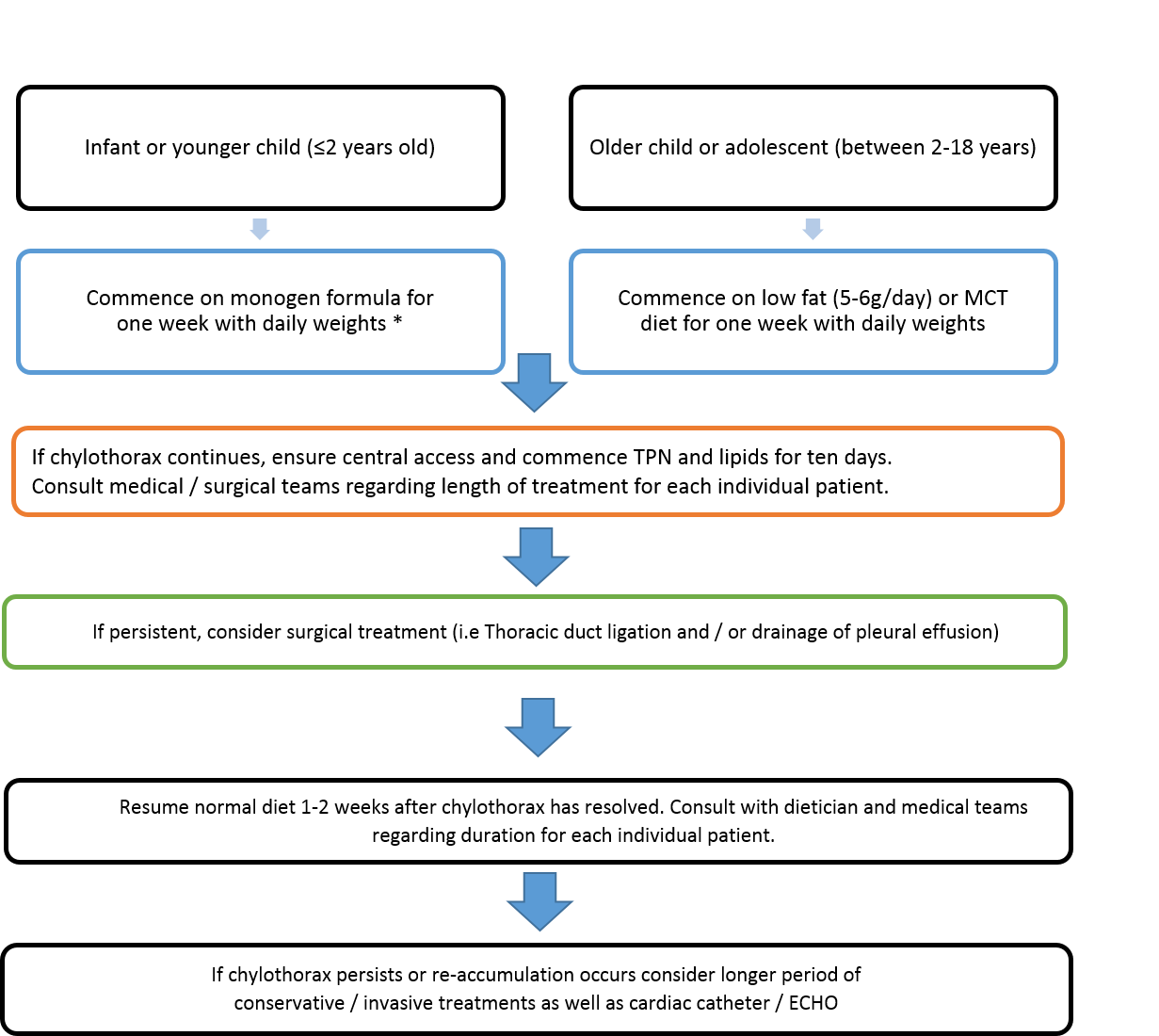

Management of Chylothorax

The management plan summarised in Figure 2 is to be followed in conjunction with the patient observations listed above. Blue - Conservative treatment; Orange – Invasive

treatment; Green – Surgical Treatment. *If the patient has a cow’s milk protein intolerance, further dietician input is required in order to prescribe an alternative formula.

Figure 2: Management of Chylothorax

Special considerations

- Children with

chylothorax going to cardiac theatre for a thoracic duct ligation

- As soon as the patient is transferred to the operating table, any existing chest drains must be connected to suction

- Instrumentation for procedures must be set up prior to anaesthetic induction of the patient as there can be significant haemodynamic changes

- In some circumstances, ward staff can prepare and ensure the availability of milk product (i.e., double cream) from dietary kitchen. The cream is fed through the patient’s nasogastric tube by the anaesthetist on induction to facilitate the obvious

leakage of chyle from the thoracic duct during surgery, therefore aiding in locating the leak

- Children with chylothorax

requiring warfarin therapy

- The loss of chyle and subsequent dietary changes may impact stability of warfarin therapy. It may be necessary to perform more frequent INR tests.

- Please ensure Clinical Haematology are aware of prescribed changes to the patient’s diet due to their chylothorax.

Butterfly Ward

Chylothorax on Butterfly Ward

For patients on Butterfly, who are typically sicker and who have diverse causes for chylothorax, management approaches differ.

Typically, these include fasting (with TPN), replacement of chylous pleural losses exceeding 50mL/kg/day (typically replacing 50% of the losses with 4% albumin every 4 hours), fluid restriction, octreotide infusion and management of hypogammaglobinaemia

with immunoglobulin transfusion.

In the setting of diastolic cardiac dysfunction, inotropes are sometimes used. Depending on the cause, most patients eventually respond to medical management and do not require surgical interventions such as thoracic duct ligation or pleurodesis. Figure 2 is not applicable to these patients.

Observations should be adhered to as described in the patient assessment section above and should include continuous cardiac monitoring.

Medical management on Butterfly

In terms of medical management, a trial of octreotide should be considered.

Octreotide is a synthetic somatostatatin analog, which is long acting. Its complete mechanism of action is unclear; however, it is thought that they may cause vasoconstriction of the splenic circulation and then a reduction in intestinal blood

flow and a reduction in the production of lymphatic fluid. Please refer to Lexicomp for neonatal dosing information of octreotide.

Possible side

effects: hyperglycaemia, hyperthyroidism, abdominal cramps, nausea, diarrhoea, renal impairment. Therefore, patients receiving octreotide

should have careful monitoring of their blood sugars, urine output and

irritability.

Ongoing management,

special considerations, and potential complications

- Monitor for malnutrition

- Ensure patient and family education (i.e chylothorax and modified diet education)

- Infection control and monitor for immunosuppression

Rosella Ward

Chylothorax on Rosella Ward

For management of chylothorax in PICU- See RCH PICU Departmental Guideline: Chylothorax

after Cardiac Surgery

Companion Documents

RCH CPGs

RCH Nursing guidelines

RCH Departmental Resources

Evidence Table

| Reference

|

Source of Evidence

|

Key

findings and considerations |

| Ascenzi, J.A (2007). Update on Complications of Pediatric Cardiac Surgery. Critical care nursing clinics of North America. 15 (9), 361 – 369. |

Systematic Review of Randomized Control Trial

|

- Observation of increased and persistent yellow serosanguinous fluid drainage at a rate of 1-2µL/kg/hr on postoperative day 1. Commenced on clear liquid diet.

- On postoperative day 2, diet advanced to include formula and cloudy white drainage noted.

- Drain specimen sent for suspected chylothorax. Detection of markedly increased triglycerides, chylothorax confirmed

- Commencement of fat-free formula (Tolorex) & diuretics

- Not resolved by day 7, nil by mouth and TPN & lipids

- Ocreotide infusion (8µg/kg/hr) commenced for an additional 48 hours • Drains removed on postoperative day 1

- Discharged home on postoperative day 16 and continued on the low-fat diet for one week

|

| Bulut, O et al. (2005). Treatment of chylothorax developed after Congenital Heart Disease surgery: a case report. North Clin Istanbul. 2(3): 227-230. |

Case Study

|

Diagnostic criteria for chylothorax diagnosis:

- Milk-like drainage

- Sterile culture

- TAG > 110mg/dL

- Lymphocytes > 1000cells/µL & ratio > 80% Chylothorax

Treatment: - Drainage of fluid

- Cease enteral nutrition

- TPN and MCT formula

- Surgery (Ligation/pleurodesis)

|

Biewer, E.S et al. (2010). Chylothrorax after surgery on congenital heart disease in newborns and infants – Risk factors and efficacy of MCT-diet. Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery. 5(127), 1-7

|

Systematic Review of Descriptive and Qualitative Study

|

- Application of MCT diet alone was effective in 71% of patients

- More invasive treatments like TPN and lipids should not be used

- After resolution of chylothorax, MCT-diet can be converted to regular milk formula within one week and with very low risk of relapse

|

| Czobor, N.R. et al. (2017). Chylothorax after paediatric cardiac surgery complications. Journal of thoracic disease. 9(8), 2466 – 2475. |

Controlled Trial

|

- The highest incidence of chylothorax was observed on the second postoperative day

- The occurrence of pulmonary failure was higher in the chylothorax group (P = 0.001) and they required longer mechanical ventilation (P=0.002) and longer hospitalisation times (P=0.001).

|

| Haines, C. et al. (2014). Chylothorax development in infants and children in the UK. Arch Dis Children. 99 (11), 724-730. |

Prospective Study |

- The incidence of chylothorax was highest in infants ≤12 months at 16 per 100 000 (0.016%)

- Most frequently confirmed by laboratory verification of triglyceride count of pleural fluids ≥1.1mmol/

- Treatment with an MCT diet was most commonly reported

|

| Milonakis, M et al. (2009). Etiology and management of chylothorax following paediatric heart surgery. Journal of Cardiac Surgery. 24 (8); 369 – 373. |

Controlled Trial

|

- 83.3% of patients (n=15) responded to conservative therapy

- Lymph leak ranged from 15 – 47 days

|

Please remember to read the disclaimer.

The revision of this nursing guideline was coordinated by Allison Ellis,

CNC, Koala and Charmaine Russell, CNS, Koala, approved by the Nursing Clinical Effectiveness Committee. Updated January 2025.