See also

Slow weight gain

Unsettled or crying babies (Colic)

Child abuse

Engaging with and assessing the adolescent patient

Key points

- Family violence (FV) has a lifetime impact on a child’s health and wellbeing. Recognising FV can be lifesaving

- Recognising the risk factors for FV followed by sensitive enquiry are the first steps in assisting families. If you notice signs of FV, ask

- FV work is difficult and not a single clinician’s responsibility to manage. Seek multidisciplinary support early

- Special consideration must be given to safe documentation in the patient’s medical record

Background

Family violence is common, and in Australia affects one in four women, with half of these women having children in their care at the time

- FV does not discriminate, it can affect anyone

- FV is not just physical; it includes psychological (including gaslighting), sexual and financial abuse

- FV tends to escalate over time, with victims living in an environment of fear, control and coercion

- Perpetrators of FV make a choice to use their power to control and dominate family members

- Reports of FV spike following disasters such as bushfires, earthquakes and floods. This includes during the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdowns

Technology is increasingly being used to abuse and control victims, examples include:

- Using phones or other GPS devices to track or stalk someone

- Abusive or threatening text messages or calls

- Sharing or threatening to share images without consent

- Monitoring and controlling communications, gaining access to partner’s passwords

- Installing spyware on personal, workplace and children’s devices

- More information about technology facilitated abuse can be found at Australian Government eSafety Commissioner

Most people do not disclose FV the first time they are asked. Do not misinterpret non-disclosure of FV as a failure

Health professionals are required by law to recognise and respond to signs a child or young person is at risk and refer to Child Protection Services

Assessment

History

Risk factors that prompt further FV enquiry

Infants and toddlers

- An unsettled baby (eg excessive crying, sleep difficulties)

- Signs of poor attachment: avoidant gaze, easy startle response

- Delayed developmental milestones

School aged child

- Recurrent abdominal pain and headache

- Regressed behaviours (eg bedwetting, using ”baby talk”)

- Poorly controlled chronic conditions (eg asthma, diabetes)

- Emotional lability, withdrawn, aggressive or anxious behaviours

- Poor concentration

- Erratic school attendance

Adolescent

- Eating disorders

- Depression, anxiety, self-harm, suicidality

- Substance use, truancy, STIs, unplanned pregnancy

Caregiver

- Is there difficulty obtaining a clear history from patient or caregiver, ask yourself why?

- Parental distress out of keeping with the severity of a child’s illness

- Reluctance to be discharged

- Frequent non-attendance or rescheduling of appointments

- Frequent presentations for a child with no clear health concern

- One parent dominating contact with medical staff

- Infrequent visiting when child admitted to hospital

- Aggressive or controlling relationship dynamics between parents

- Mental health issues

- Substance misuse

- Unexplained injuries

- Consider intersectionality: in what ways might the person be experiencing marginalisation or discrimination (eg LGBTQI, disability, mental health illness, CALD or NESB, Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander) and how might that impact their safety or ability to access support?

Examination

Risk factors that prompt further FV enquiry

Behaviour

- Are the child/siblings/caregiver:

- Withdrawn or highly anxious

- Overly familiar

- Reluctant or fearful to speak

- Hypervigilant

- Is the child taking on the parent role?

- Is the caregiver intrusive, controlling or intimidating toward child, partner or staff member?

- Look for any other signs a child is experiencing trauma of FV as listed below under Lethality risk factors

Physical

- Unexplained injuries: burns, bruises, or fractures? (see Child abuse)

- Bruising and or petechiae around neck or head could suggest recent attempt at strangulation

- Unexplained pain: abdominal pain and headache are common complaints that could be a symptom of a child’s stress or fear of going home

- Signs of neglect

Management

Do

- Trust your instincts: a feeling of “something is not right” may be the only trigger to prompt enquiry about FV

- Collaborate: ask for senior clinician help and/or consult with multidisciplinary colleagues

- Know that it takes time to feel comfortable asking about FV, practice makes it easier

- Remember how common FV is: one in four Australian women experience FV

- Listen, validate and empower. Give the victim as much choice and control as you can. Offer your support if they want assistance

Don’t

- Ask about FV when a caregiver’s partner is present, or assume it is safe to talk in the presence of another family member or child over two years of age (children can and do repeat information)

- Encourage the caregiver to leave their partner

- Blame FV behaviour or impacts on non-offending family members

- Feel you have failed if you suspect FV and a disclosure is not made

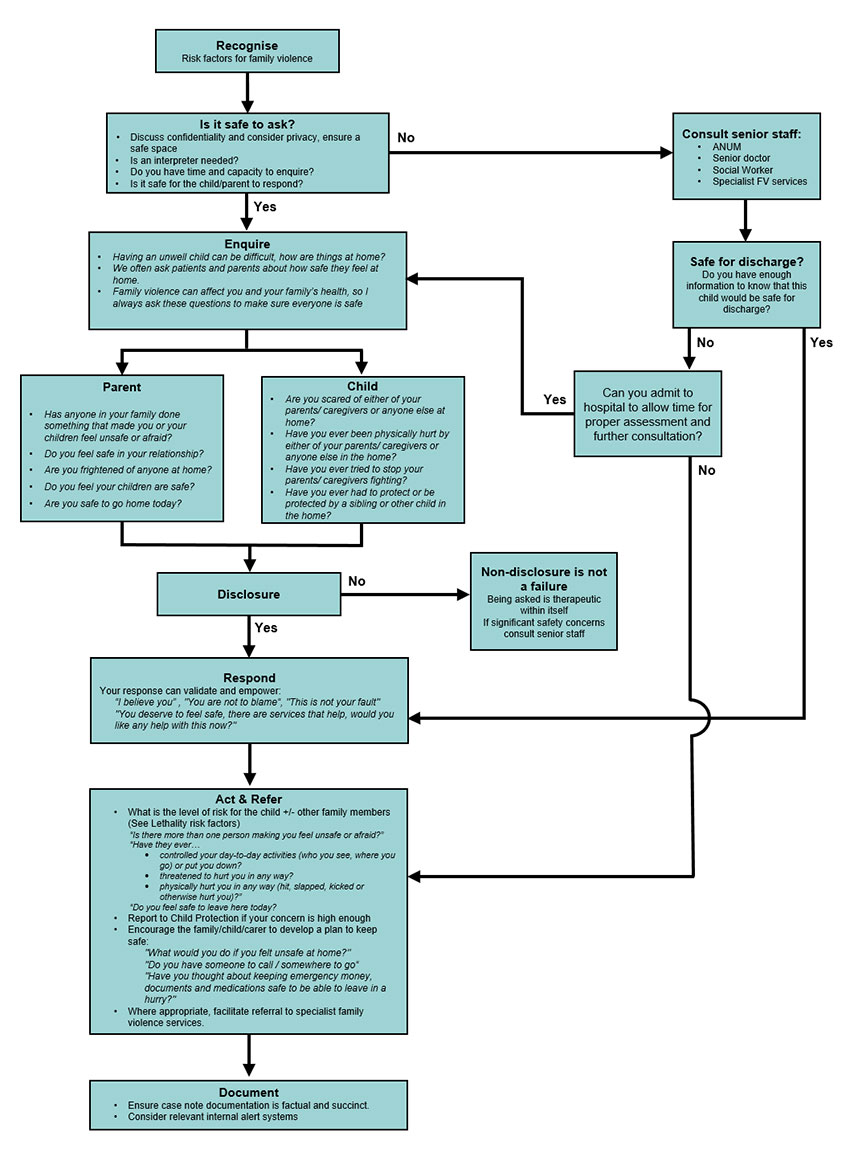

Approach to FV enquiry and response

Lethality risk factors

Victims who are experiencing any of the following are at increased risk of being killed or almost killed:

- Escalation of violence (increase in either severity or frequency)

- Recent separation or victim intention to separate

- Physical assault whilst pregnant/following new birth

- Stalking (including cyber stalking)

- Perpetrator access to or use of weapons

- Perpetrator threats or attempts to commit suicide

- Threats to harm or kill children and pets

- Perpetrator unemployment

- Sexual assault

- Strangulation or attempted strangulation

- Obsessional/jealous behaviours towards victim

- Perpetrator substance misuse

Documentation

When documenting sensitive information, it is important to use clear, succinct, factual statements

- Refer to your organisation’s guidelines for documentation of sensitive information

- To promote the safety of patient records, consider heading any notes relating to family violence with the following statement: "Third party information – private and confidential"

- With any documentation, be aware that the patient’s medical record may still be required to be released under FOI legislation, court subpoenas, or under interagency information sharing schemes

- In health services that use an electronic medical record (EMR), consider using a ‘sensitive’ encounter or episode function, to document information about family violence disclosures

- provides additional protection of the information, while keeping it available to staff who need to access it

- Where available, consider use of internal alert systems (such as “FYI” flags)

- alerts other health workers to the family violence, preventing sensitive information from being shared unsafely through patient access portals and other information sharing procedures

- Importantly, can also prevent the family member who uses violence, from accessing information about the victim, including phone numbers, addresses and appointment times

Consider consultation with local paediatric team or specialist family violence services when

- You have reason to believe this child or caregiver is not safe and requires escalation of care (see flowchart above)

- At any time, you feel uncomfortable managing the situation and need advice on how to proceed

Consider transfer when

Child requiring care beyond the comfort level of the local hospital

Consider discharge when

- After thorough clinical assessment and consultation, you are confident the child is safe at home

- If required, a safety plan has been established

- Appropriate referrals have been made

- There is a follow up plan in place

Health professionals are susceptible to FV like any member of the community. If you are experiencing FV please utilise the resources listed below

FV specialist Services (24 hours a day)

National

1800 RESPECT or 1800 737 732

Kids Help Line 1800 55 1800

The Daisy App

The White Book (RACGP resource)

Victoria

Safe Steps (Victoria) 1800 015 188

Child Protection (Victoria) 13 12 78

Parentline Victoria 13 22 89

Parent information

Kids Health Information Family Violence

Additional Resources

Victoria

MARAM Framework https://www.vic.gov.au/maram-practice-guides-and-resources

- The MARAM Framework recognises a wider range of risk indicators for children, older people and diverse communities, across identities, family and relationship types and will keep perpetrators in view and hold them accountable for their actions and behaviours. The aim of the framework is to increase the safety and wellbeing of Victorians by ensuring all relevant services are effectively identifying, assessing and managing FV risk

Last updated September 2021