See also

Resuscitation

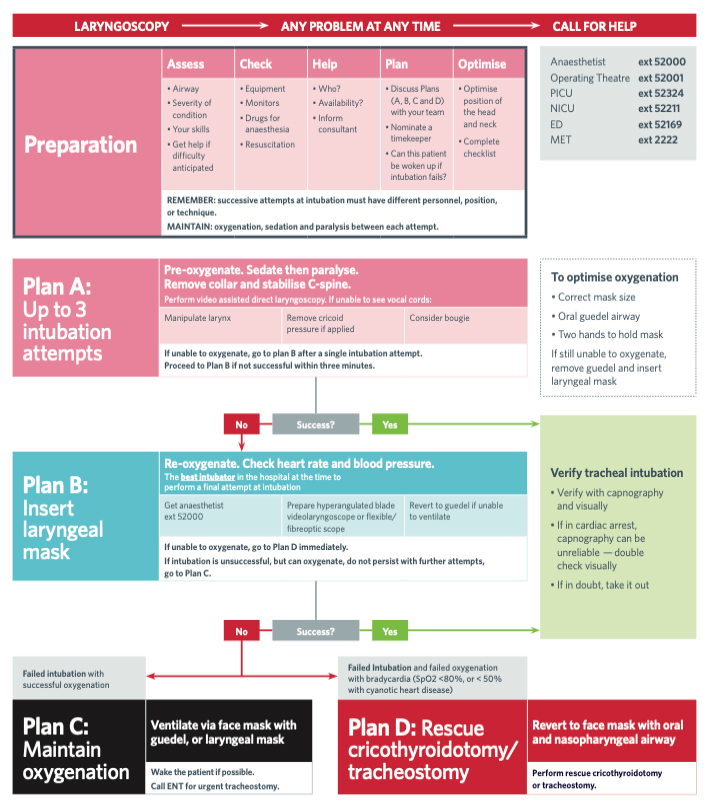

Can't intubate can't oxygenate (CICO) airway emergency management

Emergency airway management in COVID -19

Intubation checklist

Key points

- Specific measures to optimise physiology should be undertaken prior to every emergency intubation

- Every emergency intubation should include early consideration of the need for help, clear team member role allocation, a clear plan for unsuccessful intubation, and strategies to help maintain situational awareness

- An emergency intubation checklist and other cognitive aids should be used during emergency airway management

- Continuous wave-form end-tidal CO2 (ETCO2) should be used to confirm correct endotracheal tube (ETT) position

- If ETCO2 waveform is lost or child goes into cardiac arrest, reassess the child, commence resuscitation measures and check ETT position (including direct visualisation)

Background

In emergencies, problems with airway management are rarely due to anatomically difficult airways, and commonly due to physiologically or situationally difficult airways (operator experience or staffing numbers).

The strongest predictors of adverse events are multiple intubation attempts, and respiratory or cardiovascular failure as the indication for intubation

Preparation

Optimisation of the physiology

In a child with cardiac and respiratory compromise, optimise positioning, oxygenation, breathing, circulation and perfusion prior to the induction of anaesthesia

| Strategies to optimise physiology |

|

Hypoxia |

- Elevate head of bed to up to 40 degrees

- Pre-oxygenate with positive airway pressure / PEEP (BVM with PEEP valve, T-piece, CPAP, BiPAP or HFNC)

- Consider providing apnoeic oxygenation with nasal cannula oxygen 2 L/kg/min (15 L/min maximum)

- Abort intubation attempt if saturations

<93% or drop by 10% from baseline

|

|

Hypotension |

- Fluid resuscitation 10–20 mL/kg

- Consider push dose adrenaline 1 microg/kg (max 50 microg)* in non-arrested child - can be repeated as required

- Titrate induction agent dose (See Medication dosing section below)

- Consider push dose adrenaline following induction

|

* Push dose adrenaline in the non-arrested child is NOT the same as the adrenaline dose given in cardiac arrest (see Resuscitation)

Assess the airway

- Consult anaesthetics for assistance if difficult airway anticipated

- Anticipate difficulty in oxygenation by bag mask ventilation, laryngoscopy, ETT, supraglottic airway or rescue techniques

- Congenital syndromes involving micrognathia, macroglossia or midface hypoplasia and some acquired conditions are often associated with difficult airways

- There is an increased risk of airway obstruction in the setting of:

- Head injury or intoxication (loss of pharyngeal tone)

- Trauma (injury to the airway or compression due to neck haematoma)

- Airway debris (teeth, vomitus, blood etc)

- Facial or neck burns

- Inhaled smoke or liquids even in the absence of burns to the face

| Acquired conditions |

|

Pre-surgical |

Airway burns / trauma / infections / tumours

Tonsillar hypertrophy

Tracheal anomalies (subglottic stenosis)

Sleep apnoea

Foreign body aspiration |

|

Post-surgical |

Cervical spine fixation

Maxillofacial surgery

ENT surgery |

Assess the situation

Do you need help? If your assessment of the child's airway, physiological condition, or the skillset of your team raises concerns, maintain oxygenation and call for help before administering any medications. See Pre-intubation checklist below

Equipment preparation / monitoring / medications

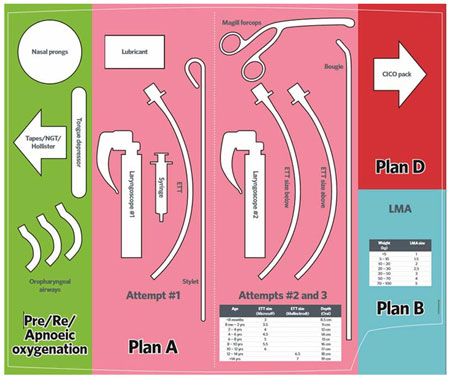

An airway equipment template should be used to minimise errors during the procedure, see an example template below. Individual centres may choose to use their own site-specific templates

Equipment should be laid out on the airway equipment template prior to emergency intubation. Equipment not on the template should be at the bedside and confirmed as functioning (T-piece, suction, video laryngoscope)

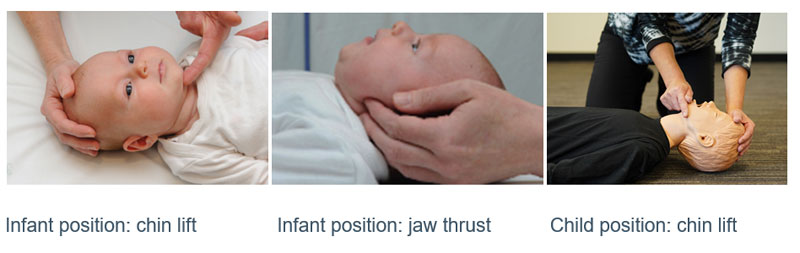

Optimise positioning for intubation as shown in figure below by

- Maintaining head in neutral position

- Open and clear the airway

- Consider using adjuncts such as nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal airways

Example Emergency Airway Template

- Monitoring should include: saturations, heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure (2-minute cycle) and ETCO2

- Induction agent and muscle relaxant should be chosen and drawn up (the dose administered may be titrated according to the child's condition). Post-intubation sedation should be prepared

|

Medication dosing |

|

Induction agent |

- All induction agents can precipitate acute hypotension if used at "normal" doses in unwell children; significant dose reduction is required. See Emergency Resources

- Ketamine (0.5–2 mg/kg) is the preferred default induction agent for most emergency intubation scenarios

|

|

Muscle relaxant |

- Higher doses may be required in unwell children to achieve normal onset of action

- Rocuronium (1.2–1.6 mg/kg) is the preferred default muscle relaxant for emergency intubation

|

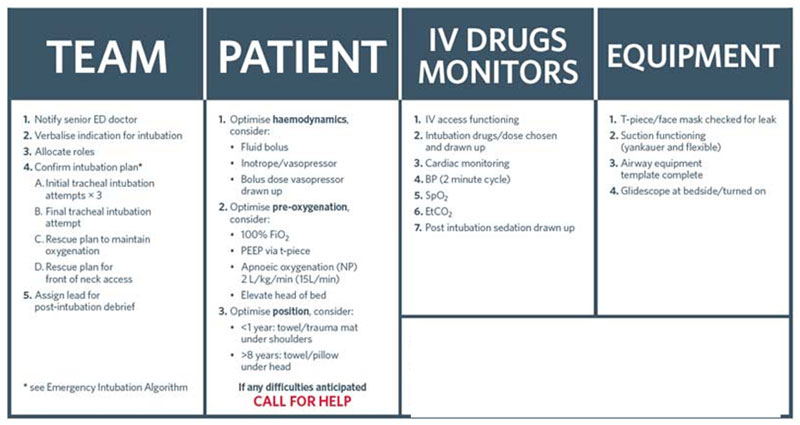

Pre-intubation checklist

The emergency intubation checklist should be read aloud in a challenge-response format by the Team Leader prior to every emergency intubation, reassessing after any single failed attempt

Individual centres may choose to use their own a site-specific checklist (

Qld,

NSW)

Please see an example checklist below

Management

Emergency Intubation (pdf)

| Cricoid force (pressure) |

- Cricoid force is not routinely used for emergency intubation Cricoid force (application of pressure to the cricoid cartilage to compress the oesophagus and prevent passive regurgitation of gastric contents) is different from external laryngeal manipulation (movement of the trachea to help glottic exposure)

- Cricoid force in children compresses the trachea, making oxygenation and intubation more difficult, results in oesophageal displacement and not compression, and decreases lower oesophageal sphincter tone, making regurgitation more likely.

|

Confirmation of tube position

Verification of correct endotracheal tube (ETT) placement is of vital importance as an unrecognised oesophageal intubation can prove rapidly fatal. There is no single method that is 100% reliable for the detection of correct placement of an ETT

The best indicators to confirm successful placement of the ETT:

- Visualisation of ETT passing through the cords: direct visualisation may not always be possible, especially in an anatomically difficult airway or an airway that is obscured by blood, secretions or vomitus. Additional objective techniques should still be used to confirm correct ETT position.

If you cannot see the cords, do not try to pass the ETT. Remove laryngoscope, reoxygenate, plan and perform subsequent attempts with a different intubator, position of the child, or intubation technique

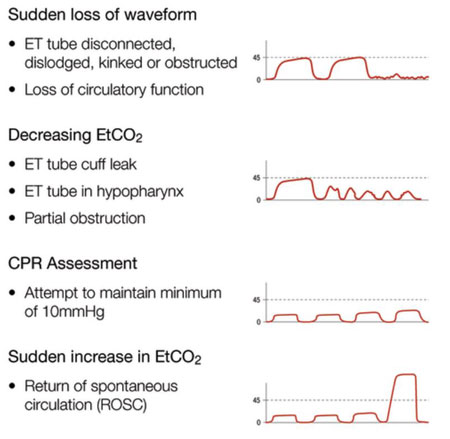

- Continuous waveform capnography (ETCO2) is the best objective method of confirmation of correct ETT placement. If the ETCO2 reads zero, the tube could be in the oesophagus or there is no cardiac output. Note that for children in cardiac arrest, or those with markedly reduced perfusion, ETCO2 determination may be less accurate. In these situations, if the ETCO2 determination is inconclusive, other methods of confirmation should be used.

If ETCO2 waveform is lost or child goes into cardiac arrest, reassess the child, commence resuscitation measures and check ETT position (including direct visualisation)

If correct placement of the ETT is uncertain despite these measures, it should be removed and reoxygenation commenced

Less reliable indicators:

- Auscultation: equal breath sounds should be heard on auscultation of both apices and high in each axilla. Also listen over epigastrium during ventilation (for ETT in oesophagus)

- Chest rise: equal rise and fall of chest during each ventilation

- Misting of ETT: observe escape of air / moisture clouding on ETT

- Pulse Oximetry: hypoxia is a relatively late (and ominous) sign with regard to determining correct ETT position. There is a lag for a few seconds until saturations start coming up after correct ETT insertion

- CXR: only useful to assess the depth of insertion of the ETT

- Ultrasound: point of care ultrasound by experienced clinician can also help confirm the correct position of ETT

Example Emergency Airway Plan

Post Intubation Care

- Secure ETT with tape / fastener (eg HollisterTM)

- Reconfirm ETT position as above

- Commence ongoing sedation

Post Intubation Debriefing

- Post intubation debriefing for team members should routinely occur. This can be a "hot" (as soon as possible after the event) or "cold" (delayed) debrief.

- This should be short (5–10 mins)

- This identifies technical and human factors that can be addressed to improve the safety of future intubations

- The attached debrief form may be used as a cognitive aid

- Emergency Airway Management Debrief Form

Consider transfer when

No facility to manage intubated children is available at local hospital

For emergency advice and paediatric or neonatal ICU transfers, see Retrieval Services

Additional resources

Airway registry information

Video demonstration of RCH CICO Pack

Last updated March 2021