Table of contents will be automatically generated here...

This information sheet is about Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA), its cause, treatment and what it may mean for your child and your family.

Hearing that your child has JIA can be a shock because people think that arthritis is a condition that only affects older people. You may feel overwhelmed by the diagnosis of JIA. This is normal - there are lots of things to think about. You will probably have

many questions. You may like to make a list of questions to ask your child's rheumatologist or rheumatology nurse educator at your next appointment. You may need to hear the answers several times. That's OK. It is important for you and your child to know about

JIA.

What is Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis?

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA) is a general name for several kinds of arthritis. "Juvenile" means that it affects young people, "idiopathic" means that we don't know what the cause is, and "arthritis" means inflammation of the joints. Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis used to be called Juvenile Chronic Arthritis

(JCA). In some countries it is called Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis (JRA), and sometimes people simply call it Juvenile Arthritis (JA).

JIA is chronic arthritis that begins in children under 16 years of age. It causes inflammation in one or more joints for 6 weeks or longer.

JIA can appear in many different ways and can range in severity. It mostly affects the joints and the surrounding tissues, although it can affect other organs like the eyes. Some of the symptoms and signs of an inflamed joint include joint swelling, pain, stiffness

(especially in the morning), and warmth around the joint. Your child may not have all of these in every joint that is inflamed. Less commonly your child may also have other symptoms such as fever, rash, loss of appetite and loss of weight.

What does chronic mean?

Conditions can be acute (starting suddenly or short-lived) or chronic (lasting longer but not necessarily forever). JIA is considered a chronic condition because the joints involved are inflammed for at least 6 weeks and while treatment can alleviate

the symptoms it does not lead to a 'cure'. This means that when a child is diagnosed with JIA, it is impossible to say exactly how long the condition will last. JIA can continue for months or years. Sometimes the symptoms go away, usually after treatment. This is

called remission. Remission may last for months, years, or for a lifetime. Up to 50% of children with JIA may go into full remission before adulthood.

How common is JIA?

JIA affects at least one child in every 1,000 in Australia. There are at least 5,000 children in Australia with JIA.

This information sheet is about Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA), its cause, treatment and what it may mean for your child and your family.

Hearing that your child has JIA can be a shock because people think that arthritis is a condition that only affects older people. You may feel overwhelmed by the diagnosis of JIA. This is normal - there are lots of things to think about. You will probably have

many questions. You may like to make a list of questions to ask your child's rheumatologist or rheumatology nurse educator at your next appointment. You may need to hear the answers several times. That's OK. It is important for you and your child to know about

JIA.

What causes JIA?

We do not know the causes of JIA. However, we do know it is an auto-immune condition. Our bodies have an immune system which fights germs or viruses to keep us healthy. Sometimes the body's immune system mistakes a normal part of the body for something

foreign (like a germ), and starts attacking the body itself. In JIA the immune system attacks the joints. This is called an auto-immune process. We don't understand precisely how, or why this happens.

JIA is not hereditary - it is not passed on from parent to child. It is rare for two children in the same family to have JIA, although this can happen. Genes do play a role, but are only one of a number of factors necessary to develop JIA.

Having JIA is no one's fault. There is nothing that anyone has done, or not done that caused JIA. There are myths that JIA is caused by being too cold, by living in a cold climate or eating particular foods. None of these actually contribute to a child

getting JIA.

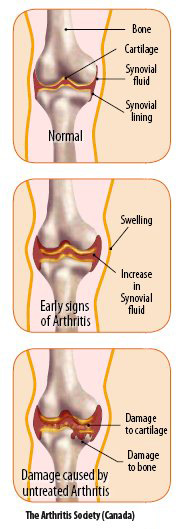

What happens to the joints in JIA?

Our bodies have many joints, such as knees, elbows, shoulder, hips. Joints are where two bones are connected in a way that lets us bend and move our limbs. To make these movements smooth, the ends of the bones are covered with smooth tissue called cartilage

(or gristle) and the joint is lubricated with a small amount of fluid called synovial fluid. The synovial fluid is held inside the joint by a capsule lined with tissue called the synovial membrane or lining. In arthritis, the synovial lining of the joint becomes

inflamed and thicker than normal, the capsule is filled with inflammatory cells, and the amount of synovial fluid increases. This can make a joint swollen or puffy . It causes pain and limits the movement of the joint. Often the joint is more stiff after

resting so joints may be more stiff and sore in the mornings. If the inflammation is not treated, it can damage the joint including the cartilage and the surrounding bone. Muscles around the joint can become weak and the joint may lose some of its range of

movement.

How is JIA diagnosed?

JIA is often hard to diagnose because the symptoms can be different in different children and can appear like some other childhood illnesses. There is no test to see if your child has JIA, and often other possibilities have to be ruled out first. This may

take time and may be hard for families who want to know what is wrong and begin treatment quickly.

Your child's doctor will ask you many questions about your child's health and will examine your child, looking for inflammation in all joints - a joint may be involved even if there is no apparent pain or swelling. Your child's doctor may ask for some of the following tests to be done:

- Blood tests to measure the amount of inflammation in your child's body and to show your child's general health. Blood tests can help decide which type of JIA your child has.

- X-rays to look at bones and joints, and sometimes at organs like the lungs and heart. X-rays cannot confirm arthritis but can exclude other bone problems.

- Bone scan to look for areas of inflammation in the body.

- Electrocardiograph (ECG) to check the heart is working normally.

- Bone marrow aspirate to look for blood disorders which can sometimes appear similar to JIA. This test is less common.

What are the different types of JIA?

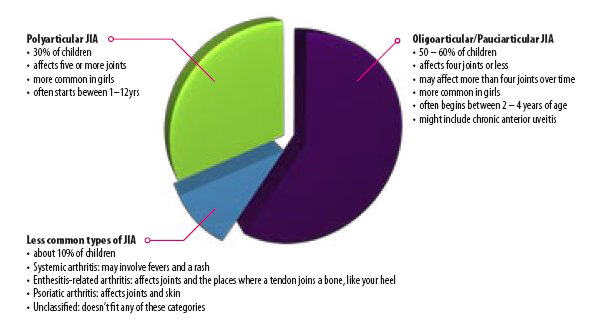

All types of JIA cause inflammation in the joints and begin before the age of 16. The different types of JIA are defined by the number of joints that are inflamed in the first six months, and by other symptoms that might be present.

Oligoarticular JIA

This is the most common form of JIA. About half (50 - 60%) of children with JIA have this type. This type of JIA:

- is also called pauciarticular JIA - "Pauci-" and "oligo-" mean 'a few' or 'not many'

- affects up to four joints in the first six months

- usually affects large joints like knees and ankles

- is more common in girls than boys

- often begins in young children between 2 and 4 years of age

- is associated with anterior uveitis - a chronic inflammation inside the eye.

This condition is explained later on.

There are two types of oligoarticular JIA based on the number of joints inflamed after six months:

- Persistent oligoarticular

About 75% of children with Oligoarticular JIA have the persistent type. Children with this type have:

- no more than four joints inflamed after six months

- usually have joints that work well

- a good chance of remission before adulthood

- Extended oligoarticular JIA

About 25% of children with Oligoarticular JIA have the extended type and will have:

• up to four joints inflamed in the first six months and

• more joints that become inflamed after six months

• less chance of going into full remission than in the persistent oligoarticular type

• with good treatment, usually have joints that work well.

More common in girls than boys, is more likely to start between 1 and 12 years of age and affects five or more joints in the first six months.

Polyarticular JIA

About 30% of all children with JIA have this type. This type of JIA:

- affects five or more joints in the first six months. "Poly-" means many

- is more common in girls than boys

- is more likely to start between 1 and 12 years of age.

There are two types of polyarticular JIA based on whether Rheumatoid Factor (RF) is found in the blood. RF is commonly found in adults with Rheumatoid Arthritis, although it can also be found in people with no arthritis at all.

- Polyarticular JIA, Rheumatoid Factor negative (RF-)

Most children with polyarticular JIA don't have rheumatoid factor in their blood (RF-). This type of JIA:

- can affect a range of joints

- can vary in how severe it is

- can vary in how long it lasts

- can go into remission in later childhood or adolescence

- may go away and then come back, or may continue into adulthood.

- Polyarticular JIA, Rheumatoid Factor positive (RF+)

A small number of children with polyarticular JIA (3 - 5%) have rheumatoid factor (RF+) in their blood. This type of JIA:

- is more likely to affect the small joints of the hands and feet to begin with

- may then spread to other joints

- sometimes includes nodules under the skin - bumps over joints, tendons, or pressure points

- is more like adult rheumatoid arthritis

- most commonly affects teenage girls

- is more likely to continue into adulthood.

Systemic JIA

This is the least common type of JIA. Systemic JIA:

- affects joints and other parts (systems) of the body such as the skin or internal organs

- often causes a fever and rash

- less often, causes inflammation around other parts of the body, like the heart or lungs

- can involve joint inflammation from the start or this may happen later

- can happen with children of any age

- affects girls and boys equally

- goes into remission after 2 - 3 years for about 50% of children, without lasting joint damage.

Enthesitis-related JIA

Enthesitis-Related JIA affects boys more often than girls.

Enthesitis means inflammation of an enthesis - a place where a tendon joins a bone. This type of JIA:

- affects both entheses and joints. The place that is most commonly inflamed is the heel of the foot, where the achilles tendon joins the bone

- usually affects only a few joints, most often the large joints in the legs, like the knees and ankles

- affects boys more often than girls

- usually happens in late childhood or adolescence

- may run in families

- is associated with a genetic marker in the blood called HLA-B27. Other family members may carry the genetic marker but never develop arthritis

- sometimes goes into remission, and sometimes continues and involves the spine

- is associated with an eye condition called acute anterior uveitis, where the eye is red, painful, watery and sensitive to light. This is not the same as the chronic anterior uveitis in oligoarticular JIA. Regular eye checks are not needed because there

will be symptoms of eye inflammation and you will know to see a doctor.

Psoriatic JIA

This type of JIA:

- is associated with psoriasis - a skin condition that causes patches of scaly skin, mainly over the elbows and knees

- psoriasis may also cause "pitting" of the fingernails - tiny dents in the nails

- the skin symptoms may begin before or after the arthritis

- the JIA can be oligoarticular or polyarticular

- the severity of the JIA may be different from the severity of the psoriasis

- occurs more commonly in girls than boys

- starts mostly in preschool children, or at around 10 years of age

- there may be psoriasis in the family.

Unclassified JIA

This is where the JIA does not fit any of the above types of JIA.

What should I know about chronic anterior uveitis?

Chronic anterior uveitis is inflammation of parts of the eye, including the iris (the coloured bit of the eye) and the ciliary body (the muscles and tissues involved in focusing the eye). This is also called iridocyclitis. As with arthritis, the inflammation

is caused by the immune system mistakenly attacking the eye in an auto-immune process. Chronic anterior uveitis doesn't have any symptoms. It doesn't hurt, and you and your child's doctor cannot tell if there is inflammation just by looking at the eye. However

if uveitis is not treated it can cause permanent vision loss. It is very important that your child has regular check-ups with an ophthalmologist (specialist eye doctor) to check if there is inflammation in the eye. The ophthalmologist will look at the eye

through a slit lamp, which allows him/her to see inside the eye. This is painless. If there is inflammation it is treated with special eye drops or other medications.

The children most at risk of developing chronic anterior uveitis are those with oligoarticular JIA with antinuclear antibodies in their blood (ANA positive). About 15 - 20% of children with oligoarticular arthritis and about 5% of children with polyarticular arthritis develop uveitis. Usually the arthritis

appears first, but the uveitis and arthritis do not follow the same course. The uveitis can even appear for the first time after the arthritis has gone into remission, so ophthalmology check ups are still required for many years.

What is it like to live with JIA?

The symptoms of JIA change over time, sometimes even day to day. Children often have times where they feel much better, and then times where they notice more symptoms and feel more tired, stiff or sore. This is called a 'flare' or 'flare-up'. Flare-ups can

sometimes be triggered by infections, and sometimes they happen without any apparent reason. If your child has a flare-up, you can contact your GP, who can assess the joints and may prescribe your child some medication for inflammation and pain. You can also call

your child's rheumatology nurse educator for advice and arrange an appointment with the rheumatologist. The flare may be managed by changing treatments for a short time, until the JIA is back under control.

Your child will need treatment for as long as the JIA continues. This may change as the JIA changes over time, but it is only stopped completely when there has been full remission for quite a while.

Just as your child's physical well-being can change over time, there are likely to be times when your child's emotional well-being may be affected by the experience of living with JIA. You and the rest of your family may also feel overwhelmed or upset about the

impact JIA has on your lives at times. This is a normal part of living with a chronic condition. It is important that you talk about these feelings with your child's treatment team, so that you, your child and family can be supported and learn to live well with

JIA.

How is JIA treated?

Because JIA affects each child differently, treatments are tailored to each individual child.

The main ways of treating arthritis include:

- medications to control the inflammation

- exercises to keep the joints moving well and the muscles strong

- splints to support the joints

- joint injections to reduce inflammation in particular joints

- pain management strategies to reduce pain and to help your child cope with pain

The goals of treatment are:

- to reduce inflammation

- to reduce pain (usually due to inflammation)

- to prevent (or slow down) the damage to joints

- to make sure joints keep working as best they can

- to get your child back to their normal activities and to prevent arthritis from interfering with a full and active lifestyle.

See the information sheet 'Treatment for JIA' for further information

Chronic anterior uveitis is inflammation of parts ofthe eye

Who are the treatment team?

You and your child

You and your child are the most important people in the treatment team. Your child's team will work together to help you and your child manage JIA. You are like the captains of the team. You should ask about the treatments suggested and how they work, so

you know what your team is offering and can work well with them.

Paediatric rheumatologist

Paediatric rheumatologists are doctors who look after children with arthritis. Your child's rheumatologist will prescribe medications, perform joint injections, monitor the progress of your child's arthritis and look for any side effects of medication.

Rheumatology nurse educator

Rheumatology nurse educators are registered paediatric nurses who specialise in caring for children and families with JIA. Your rheumatology nurse educator will provide you and your child with education & support and coordinate your child's treatment.

Physiotherapist (physio)

Physiotherapists are experts in how joints and muscles work. Physiotherapists develop exercises to keep joints moving well. They give advice on splinting and protective equipment. This can assist your child to reduce pain and the stress on inflamed joints.

Occupational therapist (OT)

Occupational therapists can provide splints for supporting joints and other aids to help your child with everyday activities like getting dressed or writing. These help your child to be independent.

Psychologist / Psychiatrist / Counsellor

Psychologists and psychiatrists are specialists in helping children and families manage social, emotional and behavioural difficulties, and mental health problems like depression and anxiety. They can also help children learn ways to manage pain. Counsellors usually work with children and families who need a

supportive person to talk to.

Your child's GP looks after the general health of your child. Contact your GP if you have any concerns about your child's health, other than joint problems.

Orthotist

Orthotists make orthotics - inserts worn in the shoe to support your child's feet.

Ophthalmologist / Optometrists

Ophthalmologists are doctors who specialise in eye problems. Ophthalmologists can check your child's eyes for signs of uveitis. An ophthalmologist is different from an optometrist who is not a doctor but can assess vision, prescribes glasses and can also

screen for uveitis.

Dietician

Dieticians can review your child's diet and make meal plans to keep your child healthy. Being underweight or overweight can be a problem in JIA.

Pain specialist

Pain Specialists are doctors who can provide medication and other strategies to reduce pain. They may work with other professionals, like physiotherapists and psychologists, to help your child manage pain in a variety of ways.

Orthopaedic surgeon

Orthopaedic surgeons are doctors who perform operations on bones and joints. Orthopaedic surgery can be useful for some problems caused by JIA.

Social worker

Social workers can find community resources to help families cope with JIA, such as support groups, financial assistance, disability pensions or respite care.

Pharmacist

Pharmacists dispense your child's medication at the chemist. It is a good idea to visit the same pharmacist each time so they can keep track of your child's medications.

Teachers

Teachers and school are very important in your child's life and need to know about your child's condition and its treatments. If you wish, your nurse educator can talk to your child's school.

Support groups

Meeting other families who have a child with JIA can be a valuable experience for your whole family. It can help to share ideas and experiences with other families in the same situation. Local Arthritis Foundations often run support groups for parents

and activities for families.

What does the future hold for your child?

It is impossible to say how your child's JIA will develop over time - every child's JIA is different. However most children with JIA grow up as well rounded people with active and enjoyable lives. With treatment, most JIA can be controlled and some of the long

term consequences avoided.

JIA may be a challenge for your child and the rest of your family, and there will be ups and downs. However, your rheumatology team will provide you and your family with treatments, support and strategies to help your child live a full and active life.

Useful websites

-

Arthritis Australia - provides information and support services in your local area

-

CHOICES for Families of Children with Arthritis - a great website from the UK providing

information for parents and a linked website for children

-

PRINTO - the website of the Paediatric Rheumatology European Society

-

American College of Rheumatology - provides information about JIA

(although it's called JRA in America)

-

The Arthritis Society Canada