Analgesia first

Early immobilisation by temporary splinting, combined with reassurance can be very effective analgesia. Pain relief can be provided by paracetamol (20 mg/kg per dose) or diclofenac (up to 1 mg/kg per dose). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents are especially useful for musculoskeletal pain. Rectal administration may be helpful in the fasting child. Procedural analgesia is very important in the ED and can be provided by many different means according to the child's needs and the clinical setting. All forms of analgesia and sedation have specific risks and benefits. Most units have clinical practice guidelines to ensure safe and effective practice. Bier's block is very useful for many forearm and wrist fractures. Entonox is also useful for simple fracture manipulations and reductions. Local anaesthetic blocks can also be useful, especially femoral nerve blocks for fractures of the femoral shaft.

Reassurance and education

No matter how trivial the injury, parents deserve an adequate explanation, appropriate advice and answers to their questions. Sometimes specific treatment is not required. Some minor buckle injuries may not require casting or immobilisation.

Simple splintage

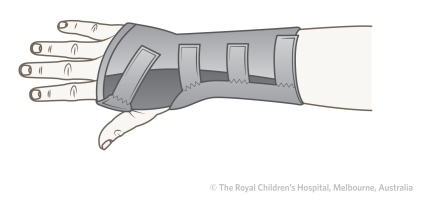

When a fracture is undisplaced or minimally displaced, reduction may not be necessary. However, the majority of fractures and epiphyseal injuries are painful and immobilisation is often the best analgesic. Removable forearm splints are ideal as primary management for undisplaced fractures of the distal radius (Figure 34). A plaster backslab does not make a buckle injury heal more quickly but it does provide excellent pain relief. Splints for these injuries should be simple and safe and easy to put on and take off. A plaster backslab, held in place with a crepe bandage can be removed by parents or at the time of review by the child's GP. Most complete plaster casts need to be removed in the ED or fracture clinic.

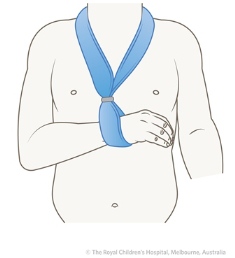

The simple formula, believed by many parents (and some doctors), that "bony injury = a plaster cast" and "soft tissue injury = a bandage" is not always true. Some upper limb fractures are best managed in a collar and cuff (Figure 35) or triangular sling. This includes most clavicle fractures and some proximal humeral fractures. Some soft tissue injuries in the lower limb, such as ankle sprains are more effectively managed in casts than with strapping because children can then weight bear with comfort and without the need for crutches. It is easier to go back to school walking in a below knee cast than trying to maintain partial weight bearing with crutches and ankle strapping.

|

| Figure 34: Removable splint for buckle injury |

|

| Figure 35: Collar and cuff for humeral fractures. |

Closed reduction and casting

Closed reduction and cast immobilisation is the treatment of choice for the majority of displaced fractures in children of all ages. Reduction is carried out under sedation, local anaesthetic block or general anaesthesia. The method of reduction varies according to the fracture type, direction and degree of displacement. The direction of fracture displacement is defined from x-rays and most reduction manoeuvres are based on reversing the forces that caused the fracture to displace. The position in cast, the type of cast and the duration of immobilisation depends on the fracture and the age of the child.

Closed reduction and three point moulding for fracture of the distal radius

Plaster casts

The most commonly used means of maintaining reduction is plaster of Paris. Plaster casts can be safe, effective and cheap. However, there are risks and casts can inflict more serious damage than the presenting injury. "Plaster can be a disaster!" Most Volkmann's ischaemic contractures are the result of immobilising the elbow in flexion, in a plaster cast, after supracondylar fractures (Figure 36).

Figure 36: A. Supracondylar fracture managed inappropriately with closed reduction, followed by a complete, above elbow cast, in high elbow flexion. This is a dangerous treatment method and can cause a Volkmann's contracture. This is a historical illustration and this method is not recommended nor used. B. Necrosis of forearm muscles following Volkmann's contracture.

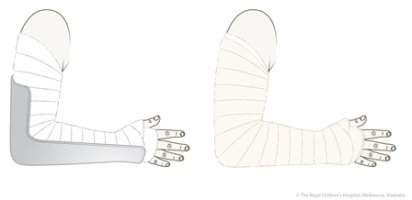

Backslabs

The backslab is the simplest and safest form of plaster splint. Instead of using encircling bandages, the plaster slabs are applied longitudinally to the limb and bandaged in place while still soft. As the plaster firms up, the slabs conform to the contours of the limb to provide support with less risk of limb constriction than with a complete cast.

Indications for backslabs include:

- Buckle injuries and minor physeal injuries at the wrist

- Most elbow fractures (Figure 37). Complete casts are not necessary and are dangerous, even if split

- Temporary support for many hand and foot injuries

- Tibial fractures with significant swelling

- Crush injuries and open fractures

|

| Figure 37: Above elbow backslab |

Complete casts

The complete cast is not easy to apply in an effective, comfortable, and safe manner. Staff should be trained and aware of the potential for cast complications. Padding used should be adequate for skin protection and comfort without being so excessive as to permit movement. Casts are seldom applied by simply winding the plaster bandages around the limb. They are constructed from a mixture of plaster slabs and plaster bandages, applied together for both strength and lightness. The extremity should be appropriately positioned for comfort and safety and to minimise the risk of fracture re-displacement.

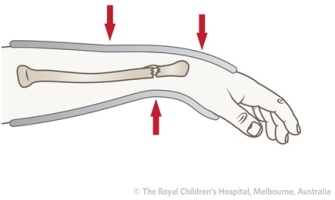

Most distal radial fractures are displaced dorsally. After reduction, the wrist is flexed and the position held by dorsal moulding of the cast, at the level of the fracture. The plaster is moulded by applying gentle pressure with the heel of the hands (not the fingers or thumbs) to the cast over the dorsal aspect of the wrist (Figure 38).

|

|

|

Figure 38: For distal radial fractures that are displaced dorsally, a below elbow cast with three point moulding in slight wrist flexion should be applied. The plaster should be moulded with the heel of the hand. The cast should not extend too distally. The child should be able to flex their metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints.

Splitting the cast

Most casts should be split after they have dried to accommodate post-reduction swelling. There are three grades of split (Figure 39):

| 1. |

A single split is carried out at the end of the operative or reduction procedure. This is routine for most cast applications |

| 2. |

The split is opened with spreaders and all the encircling bandages are divided if there is significant swelling or any signs of neurovascular compromise |

| 3. |

Two complete splits in the cast convert it to a "bivalve" for crush injuries, open fractures and fractures with overlying burns |

|

|

Figure 39: Bivalve cast splits

|

Lower limb casts

It is more difficult to apply casts to the lower limb safely and effectively. Above knee casts are usually applied with about 30 degrees of knee flexion (sometimes this is increased to about 60 degrees to discourage weight bearing) with the foot in the neutral or plantar grade position. If the ankle is immobilised in equinus (plantar flexion), the child may find it difficult to bear weight and an equinus deformity may result. It is appropriate to immobilise some very distal tibial fractures in equinus for a few weeks, as an aid to fracture reduction (Figure 40). Once pain has resolved, children are notoriously hard on casts. To prevent frequent breakages and the necessity for running repairs, many plaster casts should be reinforced with synthetic materials. In some fractures, the entire cast will consist of one of the light weight synthetic materials. These materials are more difficult to use and more prone to cause skin sores. Cast shoes (Figure 41) are more comfortable and more effective than attaching a heel directly to the cast.

|

| Figure 40: Above knee cast in equinus (plantar flexion). |

|

| Figure 41: Cast shoe. |

Cast complications

A properly-applied cast relieves pain and should be comfortable (Figure 42).

|

|

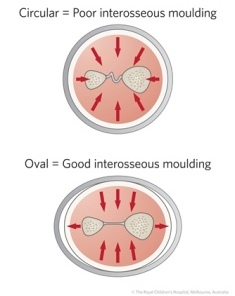

Figure 42: Casts of the forearm should have a good interosseous mould, with an oval rather than a circular cross section, because this helps to maintain tension in the interosseous membrane.

|

Many children return to the ED complaining of pain under casts, at various stages after injury:

- Early return (within 24 hours of injury): May indicate a compartment syndrome. The principal symptoms are constant, severe, progressive pain, unrelieved by simple analgesia or elevation, combined with additional pain on attempts to extend the fingers or toes.

- Early or later return: Burning pain under a cast suggests excess pressure on the skin with the risk of skin breakdown and a cast sore. Full thickness skin loss can occur under a cast in a very short period of time. Pressure over a bony prominence can proceed from inflammation to full thickness ulceration within 24 hours.

Fracture observations

Parents should be given written instructions on how to manage their child with a fracture after discharge from ED, along with a plan for follow-up.