Fracture Guideline Index

See also:

Radial neck fractures - Fracture clinics

-

Summary

-

How are they classified?

-

How common are they and how do they occur?

-

What do they look like - clinically?

-

What radiological investigations should be ordered?

-

What do they look like on x-ray?

-

When is reduction (non-operative and operative) required?

-

Do I need to refer to orthopaedics now?

-

What is the usual ED management for this fracture?

-

What follow-up is required?

-

What advice should I give to parents?

-

What are the potential complications associated with this injury?

1. Summary

Radial neck injuries are reasonably common, and when present as isolated injuries with minimal displacement or angulation, a good outcome is anticipated

However the treating clinician needs to be vigilant for any displacement of the radial head, or any co-existing injury to the ulna (including olecranon) or medial epicondyle which suggests a

monteggia equivalent injury. These injuries need early surgical intervention to prevent long term adverse outcomes.

Restriction to gentle passive pronation-supination, or severe pain with this movement should act as a red flag to prompt escalation to check carefully for a more complex injury pattern.

Severe swelling is not expected with a simple radial neck injury; its presence should also prompt investigation for a more complex injury pattern

History of significant deformity at the time of injury which has improved prior to presentation should prompt the clinician to think of a spontaneously-reduced

elbow dislocation, along with its associated complications.

2. How are they classified?

Fractures of the proximal radius can be classified according to:

- anatomical location: metaphyseal, physeal (most common Salter-Harris type II)

- degree of displacement

- presence of other injuries of the elbow/forearm (ligamentous and/or bony) - see

Monteggia Fracture CPG

- presence of elbow joint dislocation/relocation - see

Elbow Dislocation CPG

- It is important to distinguish between these as the treatment and outcome can vary significantly.

It is important to distinguish between these as the treatment and outcome can vary significantly.

3. How common are they and how do they occur?

Radial neck fractures account for 8% of all elbow fractures in children.

The most common mechanism is a fall onto the outstretched arm with a valgus stress at the elbow. They can also occur as a result of a dislocation and subsequent manual reduction of the elbow joint.

4. What do they look like clinically?

There is usually pain, tenderness, and swelling over the lateral aspect of the elbow and decreased forearm rotation (pronation/supination). Inability to perform this movement (either due to mechanical obstruction or severe pain) should prompt investigation for a more complex injury pattern.

Deformity is not typically a feature unless there are associated injuries (e.g. elbow joint dislocation, ulna shaft fracture).

5. What radiological investigations should be ordered?

Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral view of the elbow should be ordered. The degree of forearm rotation should be the same in each view (e.g. mid-position). This is to ensure that the views obtained of the proximal radius are orthogonal.

|

! |

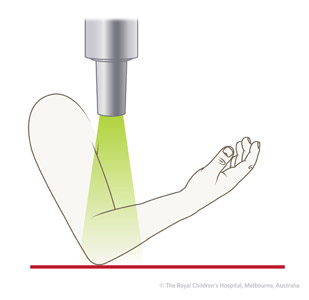

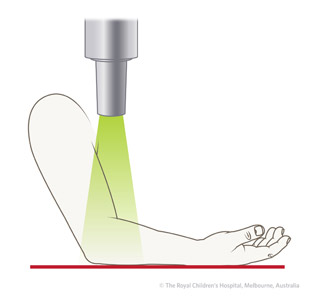

If the patient is unable to fully extend the elbow, the AP view of the elbow may not be a true AP view of the radius (Figure 1). In this situation, a separate AP view of the proximal radius may be needed to better assess the displacement (Figure 2).

|

|

|

|

Figure 1: Incorrect view. |

Figure 2: True AP view of proximal radius. |

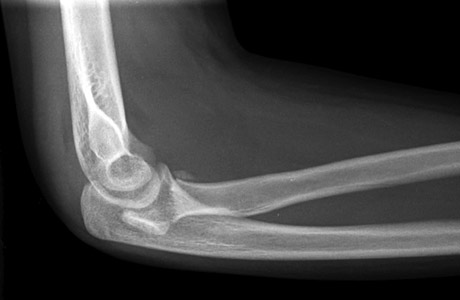

6. What do they look like on x-ray?

| ✓ |

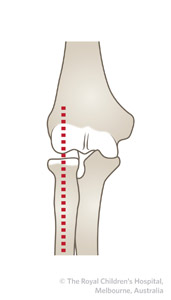

The radial head should point to the capitellum in all views (Figure 3). |

|

|

|

|

| |

A Figure 3: A) Lateral view B) AP view |

B

|

Salter-Harris type I

Figure 4: Fourteen- year- old boy with displaced Salter Harris type I fracture of the proximal radius and avulsion of the medial epicondyle -- this demonstrates the valgus nature of the force which has caused both injuries.

Salter-Harris type II

Figure 5: Four year old girl with a displaced Salter-Harris type II fracture of the proximal radius in association with a fracture of the proximal ulna (olecranon) - this is a

Monteggia variant injury requiring immediate orthopaedic referral..

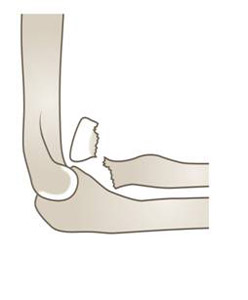

Displaced fracture of radial neck

Figure 6: Sixteen year old boy with a completely displaced and severely angulated (almost 90 degrees) radial head fracture (white arrow). The injury could be easily missed if only the lateral view is examined. Immediate orthopaedic referral required.

Figure 7: AP and lateral view of a thirteen year old girl with a completely displaced fracture of the radial neck. The fracture is more evident on the lateral view. The radial head is posterior to the capitellum, which is possibly related to the spontaneous reduction of a dislocated elbow. Immediate orthopaedic required.

7. When is reduction (non-operative and operative) required?

Any fracture to radial neck involving co-existing ulna bowing, olecranon fracture or ulna fracture should be managed as a

monteggia fracture-dislocation.

Any fracture involving displacement of the radial head requires same-day senior orthopaedic consultation

Any fractures that extend to the articular surface (Salter harris III or IV radial head injuries) should require same-day orthopaedic consultation.

Management of non-displaced isolated radial neck fractures is based on the amount of angulation between the radial head and shaft. Fractures that are angulated ≤30 degrees do not require reduction.

Any fracture reductions should be performed under x-ray image intensification under general anaesthesia by an orthopaedic surgeon. Fractures with angular deformity greater than 30 degrees usually require reduction.

However, there are a number of considerations here:

- the closer the child is to skeletal maturity, the less time there is for remodelling (in this situation, angular deformity >15 degrees may not be acceptable)

- the true degree of angulation may be more than is shown on any one standard x-ray view

- translation may compound the effects of angulation

- associated injuries mean the degree of angulation may increase

- intra-articular physeal fractures (Salter Harris type III and IV) have their own criteria for

8. Do I need to refer to orthopaedics now?

A Senior Emergency Clinician should be involved in injury evaluation and decision making in all radial neck injuries.

Indications for prompt orthopaedic consultation include:

- Fractures requiring reduction (diplaced radial head, monteggia equivalent, or articular surface involvement as above)

- An associated fracture in the same upper limb

- Extreme swelling/compartment syndrome

- Mechanical obstruction to (or severe pain with) gentle pronation/supination

9. What is the usual ED management for this fracture?

|

Fracture type

|

Type of reduction

|

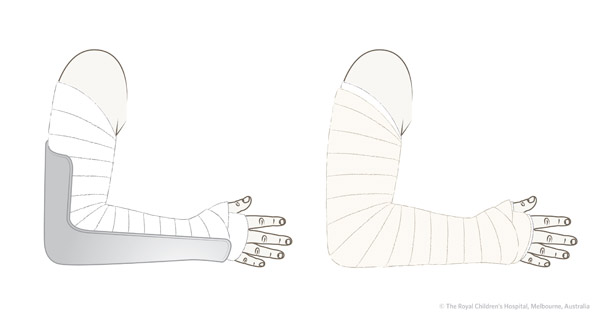

Immobilisation method & duration

|

|

Isolated, minimally displaced or angulated (≤30 degrees angulation,

<10% translation), <10 years

|

Not required

|

Above-elbow backslab (Figure 8) plus sling with elbow at 90 degrees flexion and forearm in mid-position for 3 weeks

|

|

All other fractures

|

Refer to the nearest orthopaedic on call service. Requires reduction (closed or open)

|

Refer to the nearest orthopaedic on call service

|

Table 1: ED management of radial neck fractures.

Figure 8: An above-elbow backslab is applied and then secured by a bandage.

10. What follow-up is required?

All fractures of the radial neck should have follow-up arranged in a fracture clinic within one week of injury, with an x-ray at that visit taken with the plaster removed (note this in xray request form).

This is important because:

-

the fracture displacement may worsen over the first few days

-

healing is rapid and closed reduction (the desired method) becomes very difficult after around 5 days.

-

many of these fractures are associated with other injuries around the elbow (e.g. olecranon) that may not have been evident or appreciated initially

-

Any logistical challenges arranging timely clinic should be escalated to the on-call orthopaedic consultant by phone.

As noted above, A CT of the elbow is indicated if there is doubt about whether there is any displacement of the radial head, if there is consideration of Monteggia-equivalent injury, or where there is mechanical obstruction to gentle supination/pronation of the fore

11. What advice should I give to parents?

Most undisplaced fractures do well but many can have residual become stiffness (loss of forearm rotation) even with optimal treatment.

As with other injuries around the elbow, especially when they occur in combination, there is the potential for a poor outcome. Major displacement can be associated with poorer outcome. Close follow-up (including serial x-rays without overlying plaster) is important. Whilst good management decreases this likelihood it does not remove it.

Children generally recover their elbow range of motion well and do not require physiotherapy.

12. What are the potential complications associated with this injury?

A number of specific complications can occur following this injury

-

Stiffness of forearm rotation (very common)

-

Avascular necrosis of the radial head – this is associated with greater initial displacement or delayed fixation

-

Heterotopic ossification (extra bone formation around the fracture site) leading to mechanical block

-

Physeal arrest leading to angulation of the elbow/forearm.

There are also substantial complications from delayed recognition of radial head displacement or monteggia-equivalent injury.

See

fracture clinics for other potential complications.

References (ED setting)

Evans MC, Graham HK. Radial neck fractures in children: A management algorithm. J Pediat Ortho B 1999; 8(2): 93-9.

Green NE, Van Zeeland NL. Fractures and dislocations about the elbow. In Green N, Swiontkowski M. Skeletal Trauma in Children, 4th Ed. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia 2009. p.207-82.

Herring JA. Upper extremity injuries. In Tachdjian's Pediatric Orthopedics, 4th Ed. Saunders, Philadelphia 2008. p.2451-536.

Milbrandt T, Copley L. Common elbow injuries in children: Evaluation, treatment, and clinical outcomes. Curr Opin Ortho 2004; 15: 286-94.

Singh V et al. Missed Diagnosis and Acute Management of Radial Head Dislocation with Plastic Deformation of Ulna in Children. J Pediatr Orthop 2020;40:e293-e299

Last updated May 2022

To provide feedback, please email

rch.orthopaedics@rch.org.au