This guideline should not be used outside Victoria

due to regional differences in Snake species.

See also

Anaphylaxis

Resuscitation

Key points

- Specific advice about children with potential snakebite should be sought early from a clinical toxicologist (Poisons Information Centre 13 11 26, 24 hrs/day). This should particularly occur with envenomation by snakes of snake-handlers or other sources of exotic snakes, as well as by those bitten by snakes in locations other than Victoria or Tasmania.

- In Victoria, there are 3 venomous snakes – Brown, Tiger and Red-Bellied Black.

- Antivenom should be administered early if signs of envenomation. Brown and tiger antivenom will cover all Victorian snakes.

For 24 hour advice, contact Victorian Poisons Information Centre 13 11 26

Background

Snake bite is uncommon in Victoria and envenomation (systemic poisoning from the bite) is rare. The bite site may be evidenced by fang marks, one or multiple scratches. The bite site may be painful, swollen or bruised, but usually is not for snakes in Victoria.

There are no sea snakes in Victoria, however land-based snakes can swim.

Major venomous snakes in Victoria and effects of envenomation:

| Snake |

Coagulopathy |

Neurotoxicity |

Myotoxicity |

Systemic symptoms |

Cardiovascular effects |

TMA |

|

Brown |

VICC |

Rare and mild |

- |

50% |

Collapse (33%)

Cardiac arrest (5%) |

10% |

|

Tiger |

VICC |

30% |

20% |

Common |

Rare |

5% |

|

Red-bellied black |

Mild increase in aPTT and INR with normal fibrinogen; usually no significant bleeding |

- |

Uncommon |

Common

Often significant bite site pain and limb swelling |

- |

- |

TMA: thrombotic microangiography. Haemolysis with fragmented red blood cells on blood film, thrombocytopenia and a rising creatinine.

Myotoxicity muscle pain, tenderness, rhabdomyolysis

Systemic Symptoms see

history and examination table below

VICC: Venom-induced consumptive coagulopathy (abnormal INR, high aPTT, fibrinogen very low, D-dimer high).

Assessment

Focus on evidence of envenomation.

- Once the possibility of snakebite has been raised, it is important to determine whether a child has been envenomed to establish the need for antivenom.

- This is usually done taking into consideration the combination of circumstances, symptoms, examination and laboratory test results.

- Most people bitten by snakes in Australia do not become significantly envenomed.

History and Examination

| Circumstances |

Symptoms |

Examination |

- Confirmed or witnessed bite versus suspicion that bite might have occurred

- Were there multiple bites?

- When?

- Where?

- First aid?

- Past history?

- Medications?

- Allergies?

|

- Headache

- Diaphoresis

- Nausea or vomiting

- Abdominal pain

- Diarrhoea

- Blurred or double vision

- Slurring of speech

- Muscle weakness

- Respiratory distress

- Bleeding from the bite site or elsewhere

- Passing dark or red urine

- Local pain or swelling at bite site

- Muscle pain

- Pain in lymph nodes draining the bite area

- Loss of consciousness / collapse and/or convulsions

|

- Evidence of a bite / multiple bites

- Evidence of venom movement (eg swollen or tender draining lymph nodes)

- Neurotoxic paralysis (ptosis, ophthalmoplegia, diplopia, dysarthria, limb weakness, respiratory muscle weakness)

- Coagulopathy (bleeding gums, prolonged bleeding from venepuncture sites or other wounds, including the bite site)

- Muscle damage (muscle tenderness, pain on movement, weakness, dark or red urine indicating myoglobinuria)

|

Management

Investigations

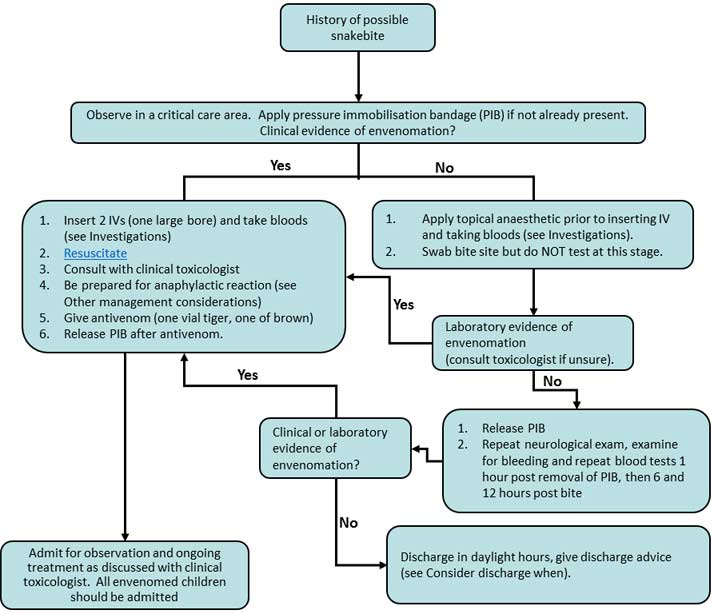

For timing and interpretation of blood tests see

management flowchart below.

- Initial blood tests: coagulation screen (INR, APTT, fibrinogen, D-dimer), FBE and film, Creatine Kinase (CK), Electrolytes, Urea and Creatinine (EUC).

- Serial blood tests: coagulation screen (INR, APTT, fibrinogen, D-dimer), FBE and film, CK, EUC.

Do not use point of care devices for coagulation profile as they are inaccurate in the setting of snakebite envenomation.

Role of snake venom detection kit (VDK)

- A VDK is rarely indicated as:

- There are only two types of antivenom required for Victorian snakes (tiger and brown) and both can be given to treat envenomation without identifying the snake, and

- The diagnosis of envenomation is based on the aforementioned history, examination and laboratory test findings. A VDK is NOT used to diagnose envenomation

- A VDK may be indicated if the snakebite is from a non-Victorian snake

- Attempted identification of snakes by witnesses should never be relied upon as snakes of different species may have the same colouring or banding

- VDKs can have significant rates of snake misidentification with both false positives and false negatives and should therefore only be performed by an experienced laboratory technician

- The results should not override clinical and geographical data. Discuss use and results with a clinical toxicologist (eg Poisons Centre 13 11 26)

- If used, a VDK should be used on a bite site swab, and a single operator should be dedicated to perform the VDK interpretation and should do so free from other clinical responsibility and interruption. This takes 20-30 minutes, and as such should be omitted in the unwell or arrested child. A brief lapse in concentration when watching for colour change in the VDK can result in a false reading

- If there is no apparent bite, a VDK may be done on urine, but never blood

Treatment

Location of care

Uncomplicated snakebites can be managed at a regional centre as long as the following resources are available:

- A doctor who is willing and able to care for the child 24 hours a day,

- Immediate access to critical care facilities,

- Immediate access to the required antivenom, and

- Access to a 24 hour pathology laboratory that can perform the required blood tests.

First aid

Apply a broad pressure immobilisation bandage,

- Preferably elastic rather than crepe, as firm as you would for a sprained ankle;

- The aim is to prevent lymphatic spread of venom, not to stop blood supply.

- Start at the bite site and bandage the entire limb.

Immobilise the joints either side of the bite site (use a splint),

Immobilise the entire child as well (lay the child down).

DO NOT remove the bandage until in a centre with full treatment facilities, as discussed above.

- If envenomed, do not remove until antivenom has been given.

- Once the antivenom has been given, remove the pressure immobilisation bandage.

- Do not wash or clean the bite site in any way (in case the use of a Venom Detection Kit is required).

Snakebite Management Flowchart

Giving Antivenom

- Antivenom is indicated in all children where there is evidence of envenomation.

- Giving antivenom should occur in consultation with a clinical toxicologist. Give one vial of tiger and one vial of brown snake antivenom without delay.

- Dilute one vial in 100mls of 0.9% saline and give IV over 15-30 min.

- If the child is in cardiac arrest and this is thought to be due to envenomation, then give undiluted antivenom via rapid IV push.

- There is no weight based calculation for antivenom (the snake delivers the same amount of venom regardless of the size of the child). One vial of antivenom is enough to neutralize the venom that can be delivered by one snake. Clinical recovery takes time after antivenom administration and multiple vials do not speed recovery.

Venom induced coagulopathy takes time to reverse.

- It takes 10 – 20 hours to start to improve and 24 – 30 hours for complete resolution.

- More antivenom than recommended will not aid recovery of clotting factors.

- The role of FFP or cryoprecipitate is controversial and should be discussed with a clinical toxicologist; generally it is indicated if the child is bleeding.

Other management considerations:

- The child should be in a critical care environment with monitoring.

- Gain 2 points of intravenous access, with at least one large bore cannula.

- There is a risk of

anaphylaxis with antivenom administration – be prepared to treat.

- If anaphylaxis occurs, treat as per the

anaphylaxis guideline and consult with a clinical toxicologist.

- Given the risk of intracerebral haemorrhage with coagulopathy and the possible elevation of blood pressure with adrenaline, a more easily titratable intravenous adrenaline infusion may be considered in discussion with an expert experienced in its use.

- Wound care: the wound can be washed after it is clear that a VDK is not required or has been used.

- Ensure that the child’s tetanus status is up to date (see

Management of tetanus prone wounds)

Consider consultation with the local paediatric team when

Serial blood tests and clinical examinations take a minimum of 12 hours after the time of the bite; these can occur in Emergency Departments or with inpatient units depending on local experience and level of comfort.

All children with evidence of envenomation should be admitted to hospital (refer to Location of care information in treatment section above).

Consider transfer to tertiary centre when

Envenomed children should be discussed with a clinical toxicologist (Poisons Information Centre 13 11 26, 24 hrs/day) and considered for transfer to a tertiary centre depending on clinical signs.

In complicated snakebites or where the above resources are not available to manage snakebite, the child should be transferred to a tertiary paediatric centre.

- If the child is significantly unwell (eg cardiac arrest, shock, bleeding) and there is no antivenom available, the retrieval team should bring the antivenom to the regional centre to be administered there prior to transfer.

For emergency advice and paediatric or neonatal ICU transfers, call the Paediatric Infant Perinatal Emergency Retrieval (PIPER) Service: 1300 137 650.

Consider discharge when

Children with suspected snakebite should only be discharged in daylight hours (neurological signs can be subtle and only evident when children are awake).

If antivenom was administered, ensure that the family is given advice on how to recognise serum sickness:

- Occurs in about 30% of children given antivenom.

- Tends to occur 4 – 14 days following antivenom administration.

- Consists of flu-like symptoms, fever, myalgia, arthralgia and rash.

- A letter should also be written to the child’s GP regarding this.

Parent Information Sheet

Snakebite – SCV patient fact sheet

Information Specific to RCH

Children undergoing serial testing are suitable for both the ED Short Stay ward and the Short Stay Unit.

Envenomed children should be considered for PICU admission but may be suitable for a ward General Medical admission depending on clinical signs and degree of coagulopathy.

Information Specific to Monash Health

The Monash Health clinical toxicologist on-call should be consulted in all cases of suspected snakebite.

Children undergoing serial bloods tests are suitable for either ED Short Stay or ward admission, depending on site.

Children who have received anti-venom may be suitable for a toxicology, inpatient or PICU (Clayton) admission depending on age and clinical features.

Last updated January 2018

|